Before he co-founded Netflix, Reed Hastings ran a debugging-tool company, Pure Software. And he’s convinced the morass of red tape he put in place at Pure led to the company’s eventual irrelevance and sale to a rival.

With Netflix, Hastings has focused on building a culture of employee empowerment — which he documents in a new business book, “No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention,” co-authored by business professor Erin Meyer. (Read our five key takeaways from the book.)

“The key is embracing managing on the edge of chaos,” Hastings says. “That’s the message of the book.” It’s hard to find fault with that approach: Netflix had 193 million streaming customers as of the end of June, nearly tripling the base in the past five years.

Hastings recently sat down (virtually) with Variety to discuss the book, as well as the most difficult Keeper Test decision he’s had to make, his one-time worry that Amazon would buy HBO, and more. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you want to write this book?

I’ve benefited so much over the last 20 years from reading other people’s books that I wanted to do the pay-it-forward thing and help the next generation of young organizations try to figure out new paradigms that are a little more post-industrial. We’ve got this industrial-factory-military-church, very top-down hierarchy model, and that’s all our societies have known for the most part. And there are other ways of operating, and we wanted to make the case that it’s good business to run without rules — which is a surprising statement.

I’ve read many CEO pontification books, and I always wonder what it’s really like in the middle of that organization. I’m always skeptical. That’s why we hired Erin Meyer, who was a business school professor first, [to co-write the book] and come in and interview hundreds of Netflix employees confidentially and then do the point/counterpoint — me pontificating, and then her doing the reality check.

It doesn’t make Netflix out to be perfect. There’s still plenty of issues. But it’s very real in that way. Our big media competitors are not going to be able to take advantage of [the lessons in the book] because they’re too well established… It’s not like some great trade secret and then they’re all going to adapt to it. It’s the younger firms that will.

In the feedback from employees in the book, what surprised you most?

How we’re super American. I had thought we had made more progress towards being really multinational, global — as great for our Singapore and Japanese and French employees. And no, we are still, you know, profoundly American.

How do you change that based on the “No Rule Rules”?

It’s especially hard in COVID. It should be a lot [more time that U.S. senior execs spend] in those countries, which we can’t do right now. But I would say [the goal is] trying to get more and more regional, where our Brazilian team can make a lot more decisions independently and our Spanish team, et cetera. So we’re making progress.

If you think of Sony, for 70 years now they’ve been global for product reasons, but they’re still profoundly Japanese. So this stuff’s hard. There’s a few that are very global — like Unilever or Adidas — but it’s a big challenge because we’re all so different.

But for us, it ties into us sharing stories from around the world, doing “Dark” in Germany and “La Casa de Papel” in Spain. Not just being Hollywood to the world, but in fact being a first-class developer and sharer of content in every major nation.

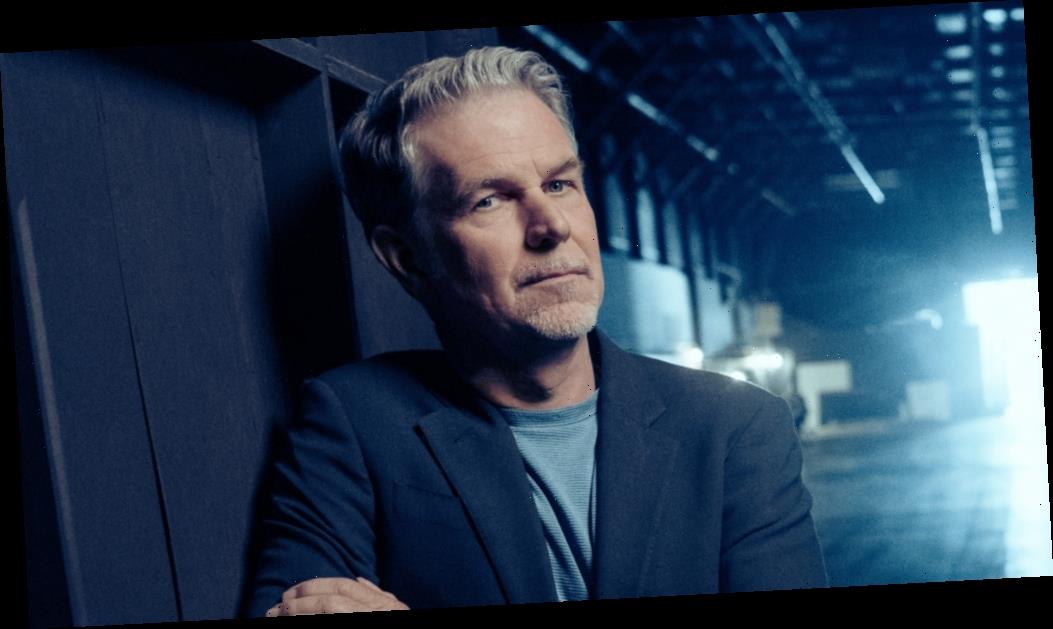

On applying the Keeper Test to ex-CFO David Wells: “That’s a tough one, because your heart cares for the person and they’re great. But your head is like, ‘We could be a better company if we had an entertainment CFO.’”

Reed Hastings

Something in the book I thought was interesting was that employees don’t need expenses approved beforehand. There’s the story of the Taiwan employee who was reimbursed $100,000 for personal vacations before he got fired. I guess that wasn’t enough to create a rule.

Correct, that was 100 grand, so in the scheme of things not that dramatic. And then the people who then feel trusted love it so much that you get better performance from them.

You say you’re running a company with no rules. But you do have rules, right? One principle you’ve never wavered on is to not introduce advertising. Isn’t that a rule made to be broken?

It’s definitely not a rule. It’s a judgment call… It’s a belief we can build a better business, a more valuable business [without advertising]. You know, advertising looks easy until you get in it. Then you realize you have to rip that revenue away from other places because the total ad market isn’t growing, and in fact right now it’s shrinking. It’s hand-to-hand combat to get people to spend less on, you know, ABC and to spend more on Netflix. There’s much more growth in the consumer market than there is in advertising, which is pretty flat. We went public 20 years ago at about a dollar a share, and now we’re [more than] $500. So I would say our subscription-focused strategy’s worked pretty well. But it’s basically what we think is the best capitalism, as opposed to a philosophical thing.

There’s another, maybe not a rule, but a judgment call if you like — that live news and sports will not be part of Netflix’s programming mix. Isn’t there a future where that would make sense for Netflix?

You know, it could. I doubt news, but sports, video gaming, user-generated content — if you think of the other big categories, someday it could make sense. But right now, Ted’s [co-CEO and chief content officer Ted Sarandos] got every billion dollar earmarked for bigger movies, bigger series, animation of course… At least for the next couple of years, every content dollar is spoken for.

In the book, you discuss the famous Netflix Keeper Test. What was the most difficult decision you’ve had to make in letting an employee go?

The Keeper Test is super simple. It’s “Would you keep the person if they wanted to leave?” I realized maybe three years ago with our CFO, David Wells, who was very competent but not hungry for entertainment. He was a generalist… He had done great work for us for a decade. I realized, if he resigned, I would look at it as an opportunity to get an entertainment CFO, who loves entertainment. That’s a tough one, because your heart cares for the person and they’re great. But your head is like, “We could be a better company if we had an entertainment CFO.” Which indeed, six months after that, is what we did [in January 2019 with the hiring of] Spence Neumann [previously Activision Blizzard’s CFO and former Disney finance exec], who’s grown up in the industry and knows it inside and out. So that’s a recent one for me.

Are you still in touch with David?

Absolutely. We’re great friends, and he’s doing a bunch of boards, including [serving on the board of] Trade Desk, the advertising company, and doing a bunch of philanthropic things. Again, he’s a very good general MBA kind of guy. It helps that he made a lot of money at Netflix.

Obviously, Ted Sarandos passes the Keeper Test. Why was it the right move to make him co-CEO [which Netflix announced in July] to be on an equal plane with you?

Well, in practice for the last several years, he’s been co-CEO in the way we operate, both finishing the other’s thoughts and him making independent decisions. And so this really acknowledged how we’ve been operating. So there’s essentially no change internally. And externally, it gives him a little more stature in doing big deals and in committing the company. We’ve been together for more than 20 years, so we’re a very effective team.

On the Netflix Q2 call, you said you’re “in for a decade.” Does that mean you’ve set a date — you’re leaving in 2030?

It means that’s the shortest I’m here. What I don’t want people to think is that I’m checking out, which would normally be the thing to be like co-CEO. I guess it is the beginning of the end in the sense that eventually, I’ll be gone. At least for the next decade, I’m super-excited by what we’re doing and full-time, so it was a statement that it’s not a short-term situation.

Some former employees have said the Keeper Test, the mandate about radical honestly and other parts of the Netflix culture create an environment of fear and anxiety. Isn’t that a net negative result from having this type of culture?

Erin Meyer talks about that in the book — she talked to one director who after one year still hadn’t unpacked their boxes. Think of a great athlete: You kind of know you could get injured, maybe even a career-ending injury, in every game. But if you think about that and if you obsess on it, it’s only going to hurt you. And you have to have the willpower to set that aside to play light, and you’re probably safer for doing that. So we have to hire the psychological type that can put that aside and who aspires to work with great colleagues and that that’s their real love, is the quality of their colleagues or the consistency of that, versus the job security.

If someone mostly cares about job security — maybe they’re supporting relatives, there are a lot of reasonable reasons — we try to be clear: We’re not a good place to come. We don’t want people to feel debilitating fear; obviously that’s not productive. But again, it’s kind of like athletics. We’re looking for a special kind of person who can ignore that fear and play light and know if they do one to 10 years at Netflix, it’s going to help their career. They don’t have to be at Netflix forever.

Aside from Qwikster [the short-lived name picked for Netflix’s DVD business when the company it split off from streaming in 2011, a decision Hastings shortly reversed], which you discuss in the book, are there any decisions you would go back and redo?

I think in hindsight, because it worked out, I would say we could have done more in original programming faster. With animation for example, there’s such long lead times there. That’s in easy hindsight. By and large, I think, we’re pretty bold at it and learning, doing better and better. Obviously, you saw the Emmy nomination count [Netflix is up for 160 Emmy Awards this year, the most of any network], you see the subscriber growth, so we’re making good progress.

On competition: “It’s only in the old communist states of the 1960s when you’d have a single network. No one wants to create that.”

Reed Hastings

How worried are you about production shutdowns because of COVID? Does Netflix need to shift more content spend to licensing versus originals?

This year, we’ve got “The Crown” [Season 4, premiering Nov. 15] and other originals; that’s all stuff filmed pre-COVID. Next year, we’ve planned out the year — we’ve got a great selection of content. It’s still more originals than this year. It’s not up by as much as we first forecast, but it is up on a year-over-year basis. Of course in Europe we’re producing, in Asia we’re producing. We’re all hopeful for a vaccine, so we can get back to more intensive work.

Netflix benefited in the first half of the year from unprecedented net adds because of the coronavirus. Do you think this is a permanent step-change?

I think once we get the vaccine, people are going to go back to sporting stadiums, you’re going to more or less return to what we considered normal. It’s hard to say, but we’ll see. People will go to theaters, to a degree, we’ll have to see — that will be slower and harder — and restaurants. I haven’t eaten at a restaurant for seven months… I’m dying to go!

Competitors you’ve cited in the past span everything from sleep to YouTube to Fortnite. Isn’t Amazon really your biggest direct competitor, with its global footprint?

You know, Amazon, Hulu, Netflix and YouTube all launched in the 2005-2007 period. So those four have been competing for 14 years now. We compete through focus. Amazon, you can get anything you want at Amazon — they’re trying to be Walmart. We’re more a passion brand; we’re more like online Starbucks or something. We’re a real entertainment brand, much more like HBO. The old fear used to be Amazon buys HBO — because it’s then Amazon-powered but entertainment-focused. But that never happened. We compete with them by doing great content. You know, pleasing people, but really it’s the focus of the brand — that’s what people talk about.

Where does Netflix go from here? There’s a section of the book about what’s to come. What are the big areas of opportunity and challenges?

What’s next is becoming a great Turkish developer of content, becoming a great Egyptian developer of content, and sharing that with the world.

In the book, you acknowledge that these “No Rules Rules” are not for everybody. You’re not going to run a nuclear power plant like this. You suggested traditional media companies can’t change their stripes. But couldn’t they adapt and steal your secret sauce?

It’s very challenging for any large and older institution that has a set of processes and values to change materially. So I don’t that that’s a big risk. In fact, in many things, we cooperate with the other entertainment companies — like antipiracy, those kinds of things. It’s not like they are our mortal enemy, and if they have great titles it grows the total market as opposed to taking away from us. It’s kind of like a race where we’re all trying to please the consumer, but there’s multiple winners in the race. And sure, we would like to get the gold medal, but silver’s awfully good too.

There are other companies that run in similar ways to Netflix. Aren’t you just operating like a big Silicon Valley startup at this point?

Well, there’s a lot of Silicon Valley companies that are big on process, Google in particular. And again, there’s a lot of small entertainment companies that are super flexible and informal and creative. Think of it mostly like, the normal cycle is, you start small and innovative. And as you grow, you choose to put in process… and what happens is you get sucked into process trying to be better. But in fact you just get very rigid.

The key is embracing managing on the edge of chaos. And as long as you are tolerant of managing on the edge of chaos, of course there’s going to be some mistakes — but there’s also going to be a lot of innovation. That’s the message of the book.

How have you resisted putting in more processes as Netflix has grown?

It was the scar of Pure Software. We stopped being innovative. We were all about process. And then the market shifted — in that case, it was C++ to Java, but it doesn’t really matter — and we were unable to pivot and ended up selling to our largest competitor. So it ended up as a really good success financially, but it did not become an epic, world-changing company in the way we want to make Netflix.

Have you used Peacock or HBO Max? What do you think?

I’m the wrong consumer [to ask]. You know, I’m a lifetime HBO [viewer]; I’m like elite-y that way. I hardly watch any broadcast television. But again, that’s not representative of the general market. But look, it’s great that they’re all in the market. Disney Plus at over 60 million is, you know, fantastic.

They’re coming for you.

Well… if you take a look at it, that’s probably true. But I would say, there’s a couple of big networks. That’s a healthy situation, right? Because you’ll continue to push each other to innovate and entertain people. It’s only in the old communist states of the 1960s when you’d have a single network. No one wants to create that.

Source: Read Full Article