How Casanova, the world’s greatest lover, sired a child… with his own 17-year-old daughter: From threesomes with nuns to underage sex, a new biography reveals the sinister side of the 18th century womaniser

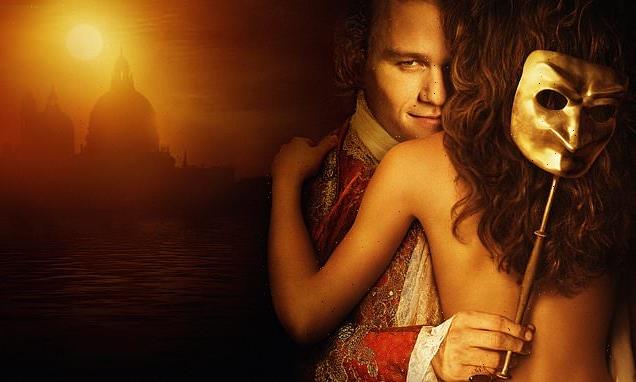

On that winter’s night in 1753, Giacomo Casanova spared no expense in seducing the bewitching nun who had escaped her convent to spend the evening with him.

Disguised in men’s clothing and brought to him by gondola, ‘M.M.’ was welcomed by Casanova at one of the many opulent love nests available for rent in Venice, then the illicit pleasure capital of Europe.

His memoirs described how one room was decorated with porcelain tiles depicting ‘couples whose voluptuous postures inflamed the imagination’.

In another, the octagonal walls, ceiling and floor were covered in splendid Venetian glass, ‘arranged in such a manner as to reflect on all sides every position of the amorous couple enjoying the pleasures of love’.

Their sumptuous dinner, delivered via dumb-waiter so no servants intruded on the lovers, included oysters whose supposedly aphrodisiac qualities fuelled a love-making marathon lasting seven hours.

In 1753, Giacomo Casanova spared no expense in seducing the nun who had escaped her convent to spend the evening with him. Pictured: 2005 film Casanova, starring Heath Ledger

‘I varied our pleasures in a thousand different ways, and astonished her by making her feel that she was susceptible of greater enjoyment than she had any idea of,’ wrote Casanova.

‘Before she left my arms, she raised her eyes towards heaven as if to thank her Divine Master.’

This was typical of the bragging in the legendary lover’s memoirs. Running to more than 3,000 pages and spanning six volumes, they make much of the great satisfaction he brought his female conquests.

There were at least 100 of them and their mutual enjoyment of sex was clearly important to him, as was the frisson of risk in many of his dalliances.

One with ‘Mme. X’, the mayor of Cologne’s wife, took place in a bedroom near that in which her husband was sleeping.

Since he could not be seen entering their house at night, Casanova crept in via a door connecting it to a neighbouring chapel, hiding in the confessional until his opportunity came.

Later writing of the ‘shared delights’ of this ‘happy night’, he was in some ways a very modern thinker — dismissing the prevailing view that women should find no fulfilment in sex.

His memoirs described how one room was decorated with porcelain tiles depicting ‘couples whose voluptuous postures inflamed the imagination’. Pictured: Heath Ledger in the 2005 film

Yet, as a new biography describes, so much else about him was ‘disturbing and sometimes very dark’.

‘In fiction, such a character might be a charming rogue,’ writes historian Leo Damrosch. ‘But Casanova’s behaviour was often far from charming.’

One theory explains his lifetime of determined sexual conquest as an attempt to recapture the intimacy denied him by his mother, Zanetta, in the years following his birth in Venice in April 1725.

An alluring actress rumoured to have had an affair with the Prince of Wales, the future George II, during a tour of England, she abandoned her husband, also an actor, and moved to Germany when Casanova was ten.

He was left in the care of his maternal grandmother, who was delighted when her grandson reached 13 and a local Catholic priest named Father Tosello suggested that he should take holy orders. But Casanova was an unlikely servant of God.

Given the ‘tonsure’ haircut designed to encourage humility in monks, he curled and perfumed the ugly ring of hair which was all that remained of his locks.

Unusually tall — he grew to 6ft 3in at a time when the average man was 5ft 6in — he was ‘built like Hercules’ according to one contemporary.

And although his swarthy complexion was unfashionable in days when fair skin was in vogue, a collection taken up following one of his early appearances in the pulpit contained several very unholy love notes penned by members of the congregation.

His admirers included Father Tosello’s niece, Angela. They met when he was 16. She was probably younger than him, as were her friends, Nanette and Marta — sisters she knew through her embroidery class.

Running to more than 3,000 pages and spanning six volumes, Casanova’s (pictured in a portrait) memoirs make much of the great satisfaction he brought his female conquests

One day the four of them met at the house where the sisters lived with their aunt. At nightfall Casanova pretended to leave but slipped back in with two bottles of wine.

When their remaining candle burnt out, they began playing blind man’s buff in the dark.

Groping for the girls, he had no idea which was which but there was no uncertainty when, on a subsequent evening, this time without Angela in attendance, he shared a bed with both of the ‘angels’ and taught himself a valuable lesson.

‘In my long career as a libertine, during which my unquenchable penchant for the fair sex made me employ every method of seduction, I learned early that a girl is reluctant to let herself be seduced because of lack of courage, whereas when she is with a friend she yields more easily.’

An exceptionally bright young man, Casanova had degrees in both civil and ecclesiastical law by the time he was 17. He was also fluent in French and learned to play the fiddle, but it was his erotic studies that seemed to most concern him.

With arranged marriages the norm, he found an easy target in unloved wives whose husbands had married them only for their dowries.

While still at the University of Padua, he joined a wedding party where he spotted that the groom only had eyes for his new wife’s sister, and ravished the neglected young bride in a carriage soon afterwards.

‘I seized her by the buttocks and carried off the most complete victory that ever a skilful gladiator did,’ he crowed.

His penchants included seeing women dressed as men and in 1743, while staying at an inn in the city of Ancona, he met a poor woman from Bologna, along with four children.

There were at least 100 conquests and their enjoyment of sex was important to him, as was the frisson of risk in many dalliances. Pictured: Richard Chamberlain in the 1987 film Casanova

One of her two sons, Bellino, was supposedly a ‘castrato’ — a choirboy castrated before the age of nine to prevent his voice breaking.

Believing that Bellino was, in fact, a young woman whose mother hoped to cash in on the demand for such performers, Casanova paid to ‘learn everything’ and his suspicions were confirmed when Teresa, her real name, revealed herself to be a 17-year-old girl in male garments.

Her younger sisters, 11-year-old Marina and 12-year-old Cecilia, were also prostituted to him by their mother — far from the last instance of such shocking abuse on his part.

‘All his life Casanova was attracted to young girls,’ writes Leo Damrosch. ‘And Cecilia and Marina were very young indeed.’

As the author points out, the age of consent in many European countries was then only ten but it’s impossible to see this as anything but ‘disturbingly exploitative’.

That same year, Casanova became private secretary to a cardinal in Rome but was sacked for helping his French tutor’s daughter to elope with her lover. With his career in the Church effectively over, his life went down astonishingly varied paths.

Travelling throughout Europe, he served a brief period in the army, failed as a professional gambler, played the fiddle in theatre orchestras, spied for the government in France and set up that country’s first state lottery.

But his main income came from a succession of rich patrons he conned into funding his philandering.

Among them was Senator Matteo Bragadin, a member of one of Venice’s most distinguished families.

Discovering that he and his friends were devotees of the occult, Casanova persuaded them that he had magic powers and was guided by a spirit called Paralis.

From then on, Bragadin treated him as an adopted son, providing him with an apartment within his palace, along with elegant clothes, his own gondola and a regular allowance.

Yet, as a new biography describes, so much else about him was ‘disturbing and sometimes very dark’. Pictured: Portrait of Casanova in Venice

Such connections protected Casanova when, at 20, he took up with a group of rowdy youths who abducted a married woman from a tavern in Venice and subjected her to a gang rape.

Yet Casanova insisted she had laughed gaily throughout and even thanked them when they dropped her back at home.

As Casanova recalled, her husband filed a complaint with the city’s judicial council but no action was taken because ‘they would have had to punish a patrician’.

His fortunes transformed by his friendship with Bragadin, Casanova felt confident in wooing women who would have had no interest in a theatre violinist. At 28, he set his sights on ‘C.C’, the 17-year-old daughter of a wealthy merchant.

To protect her from his advances, her father sent her to a convent on the Venetian island of Murano but Casanova discovered her whereabouts and wooed her through the grille separating nuns and visitors.

As he did so, he was being admired by another inhabitant — the ‘M.M’ he invited to that mirrored love-nest.

Sneaking out of the convent through a secret door in the garden, she met Casanova on several occasions, once arriving in her habit.

He found this so stimulating that he begged her to keep it on, to which she replied, ‘Thy will be done’ and sank back in readiness on the sofa. As he admitted, the fact that she was a bride of Christ made it all the more exciting.

On another evening, they were joined by C.C. who, it transpired, had already been intimate with M.M in the convent.

And, as if this menage a trois with two bisexual nuns was not scandalous enough, they were watched through a peephole by another of M.M’s lovers — the French ambassador to Rome — an arrangement to which Casanova happily agreed.

For many years it seemed he could get away with anything, but his libido eventually got him into trouble.

One theory explains his lifetime of sexual conquests as an attempt to recapture the intimacy denied him by his mother, Zanetta. Pictured: Casanova in Corfu daughter of Count Bonafede

After attempting to bed the mistress of one of Venice’s three Inquisitors — capable of having anyone deemed a threat to public order killed without trial or charge — he was imprisoned in 1755 for practising magic and exacting money from his patrons.

A year later he staged a remarkable escape by cutting through the roof of his cell with a sharpened bolt from his bedstead, before making his way to the mainland by gondola.

Knowing he could never return to Venice, he spent much of the rest of his life fleeing from one European capital to another, as various frauds — among them cashing forged bills of exchange — threatened to catch up with him.

This flight from justice led him to Florence in 1760 and one of the most disturbing of his outrages. He became smitten with a 17-year-old girl named Leonilda who seemed oddly familiar to him.

The reason became clear when he met her mother, Lucrezia, a former lover. Eschewing the crude condoms of the day — ‘I like the little fellow better quite naked’ — he had fathered several children, Leonilda among them.

Even after discovering this, he made love to both women simultaneously and Leonilda subsequently gave birth to a boy who was both Casanova’s son and his grandson.

Unabashed by this incestuous union, he expressed regret only a few times in his memoirs.

Once was when, as he approached middle age, he found himself unable to satisfy a lover named Henriette with ‘the same vigour’ he had once had.

‘Not only did he take pride in his virility, he practically defined himself by it,’ writes Leo Damrosch, and such moments filled Casanova with despair.

Worse was to come in 1763 when he visited London and was beguiled by 16-year-old Marianne Charpillon, a beauty with blue eyes, chestnut hair and ‘skin of the purest whiteness’.

Although she flirted with him, he found Marianne in flagrante with her male hairdresser one evening and realised that her apparent interest was merely a ploy by her crooked mother to coax money out of him.

Increasingly poverty-stricken, he spent his final 13 years as a librarian in a remote Bohemian castle. Pictured: David Tennant starring as Casanova for a BBC series

‘It was on that fatal day that I began to die and had finished living,’ he wrote.

Putting lead weights in his pockets, he intended to kill himself by jumping off Westminster Bridge, but was diverted by a passing acquaintance who took him to a pub where they got drunk and enjoyed watching a naked prostitute dancing a hornpipe.

Afterwards, he trained a parrot to say ‘Charpillon is more of a whore than her mother’.

While he could be prosecuted for libel, the parrot could not and he paid a servant to carry the bird around London’s fashionable watering-holes as it screeched the insult.

Not even this revenge could salve the sting of realising that he was no longer irresistible, rather what he called ‘a contemptible fool’, and Leo Damrosch describes ‘a noticeable flagging of energy’ in his memoirs in later years.

‘It’s evident that… he was beginning to feel that he was just going through the motions,’ writes Damrosch and, try as he might, he would never fully recover his confidence as a lover.

Increasingly poverty-stricken, he spent his final 13 years as a librarian in a remote Bohemian castle. There, he wrote the memoirs published in their unexpurgated version only in the 1960s — nearly two centuries after his death in 1798.

They have helped make his name synonymous with womanising but the real Casanova went far beyond that, and much of what he got up to would earn him a hefty and much-deserved prison sentence today.

Adventurer: The Life And Times Of Giacomo Casanova by Leo Damrosch is published by Yale University Press.

Source: Read Full Article