Volcanic gases at Yellowstone volcano have helped scientists better understand when elements like carbon, oxygen and nitrogen arrived on Earth. Until now, scientists believed large amounts of these “volatile elements” were wiped out about 4.5 billion years ago when a Mars-sized object struck the planet and formed the Moon, but were later resupplied through asteroid and comet impacts. But new research led by geologists from France has challenged the theory by analysing the chemical composition of gases trapped thousands of miles bellow Yellowstone National Park.

The research was carried out by scientists from the Centre de Recherches Pétrographiques et Géochimiques in France, Oxford University in the UK and the Instituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia in Italy.

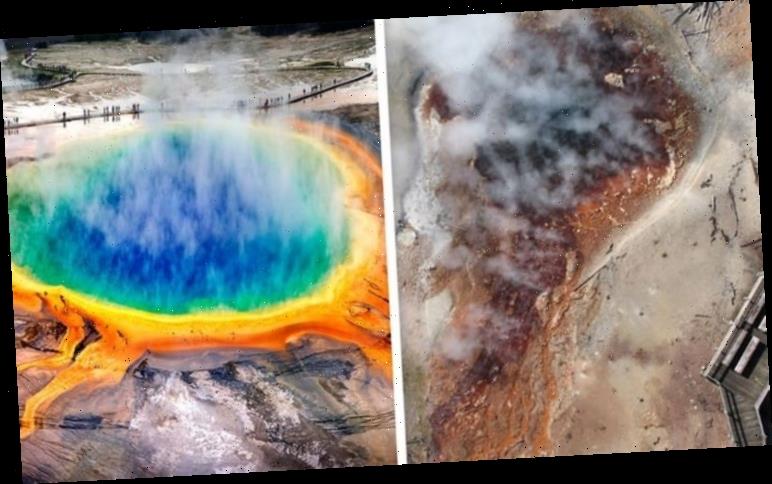

Dr Peter Barry, of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Oxford, said: “Yellowstone is the ideal location to study Earth’s primordial chemistry, as the volcanic gases released there have a source deep within the planet, providing a view of the most pristine parts of Earth’s interior.”

By analysing small amounts of the gases krypton and xenon, the scientists were able to determine the origins of volatile elements such as water deep underground.

Krypton and xenon are classified as noble gases, meaning they are not affected by chemical and geological processes.

READ MORE

-

NASA news: This time-lapse of the Sun from 20 MILLION GB of data

As a result, the gases act as a fingerprint of sorts, keeping track of where volatiles came from, even after 4.5 billion years of Earth’s history.

The researchers found these fingerprints closely match signatures obtained from meteorites.

However, the study has also found many of the noble gases trapped within the Yellowstone mantle have been trapped for most of Earth’s history.

A key gas used in this study was an isotope of xenon known as xenon-129.

According to Professor Bernard Marty, from Université de Lorraine, there are nine isotopes of the noble gas – variants in the number of neutrons within an element.

Yellowstone is the ideal location to study Earth’s primordial chemistry

Dr Peter Barry, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

But xenon-129 is unique because it forms from the radioactive decay of iodine-129.

Iodine-129 has a very short half-life and it has all decayed into xenon-129 after the first 100 million years of Earth’s history.

The noble gas was then trapped in place, giving scientists a chance to study it.

The researchers found the xenon gas at Yellowstone is different from the gases found at other volcanoes where the samples are much closer to the surface.

DON’T MISS…

Unexpected structures found near the Earth’s core [INSIGHT]

Why Yellowstone could erupt faster than thought [ANALYSIS]

Black holes: Astronomers find ‘strange’ objects in the Milky Way [INSIGHT]

READ MORE

-

Asteroid news: Astronomers confirm a ‘very close encounter’

As a result, the gas most likely mixed between the deep mantle and the amount of material arriving late on Earth’s surface would have been limited.

The findings suggest Earth kept onto its volatile materials despite its violent formative days.

The findings also suggest the late delivery of volatiles through comets and asteroids may not be necessary to explain the origins of life on Earth.

The study, supported by the European Research Council, the Deep Carbon Observatory and the Sloan Foundation was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

The study reads: “Volatile elements play a critical role in the evolution of Earth.

“Nevertheless, the mechanism(s) by which Earth acquired, and was able to preserve its volatile budget throughout its violent accretionary history, remains uncertain.

“In this study, we analyzed noble gas isotopes in volcanic gases from the Yellowstone mantle plume, thought to sample the deep primordial mantle, to determine the origin of volatiles on Earth.

“We find that Kr and Xe isotopes within the deep mantle have a similar chondritic origin to those found previously in the upper mantle.

“This suggests that the Earth has retained chondritic volatiles throughout the accretion and, therefore, terrestrial volatiles cannot not solely be the result of late additions following the Moon-forming impact.”

Source: Read Full Article