In an age of selfies and Instagram, it’s easy to forget how rare and special photographs once were. How powerful a tool they can be in both documenting history and suggesting cultural narratives. Writer and curator Catherine E. McKinley, who specializes in African photography, has spent a lifetime thoughtfully collecting images of Black men and women whose fuller stories may elude us, but whose photographs offer viewers snippets of histories in which others might find glimpses of themselves.

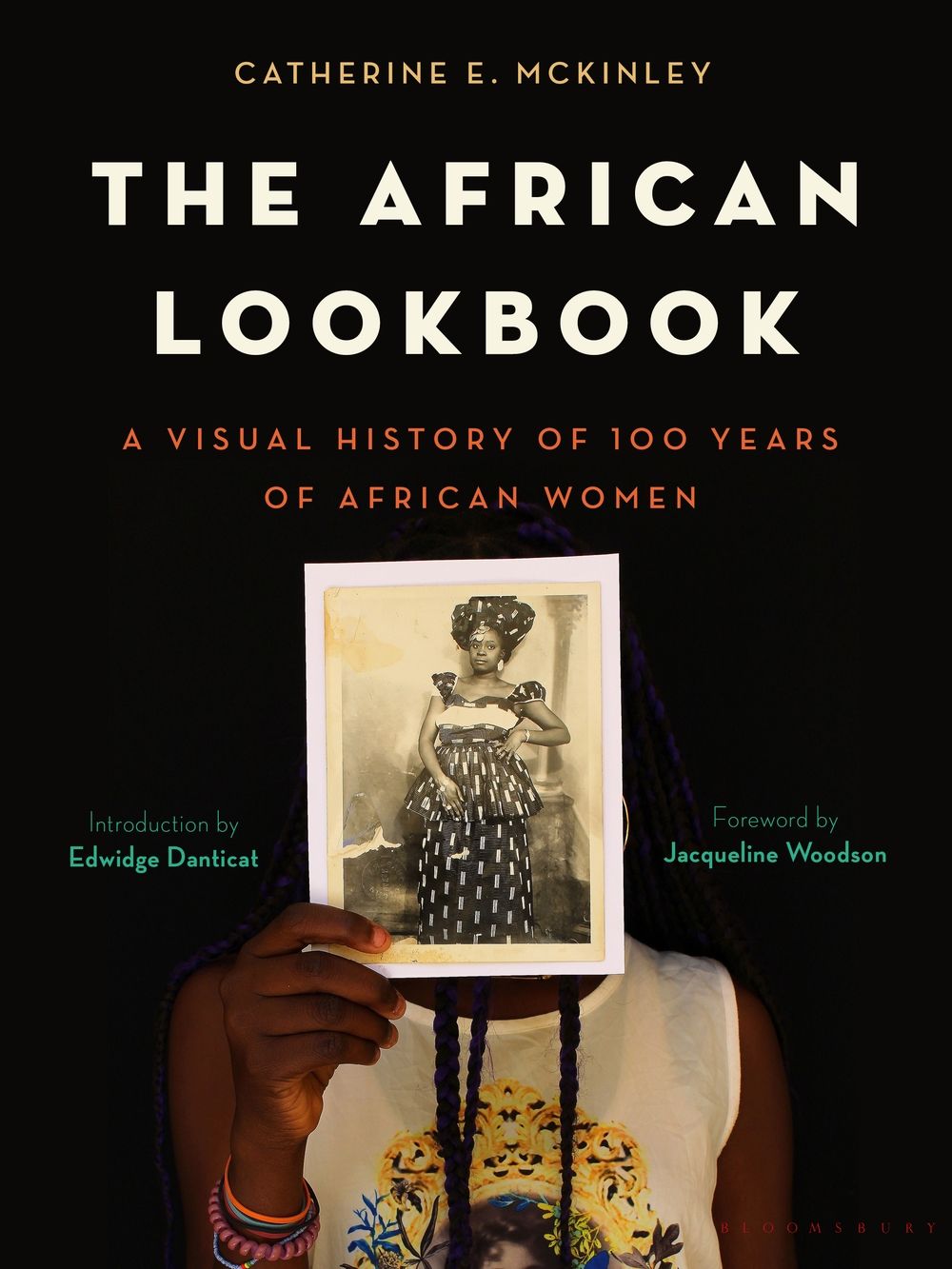

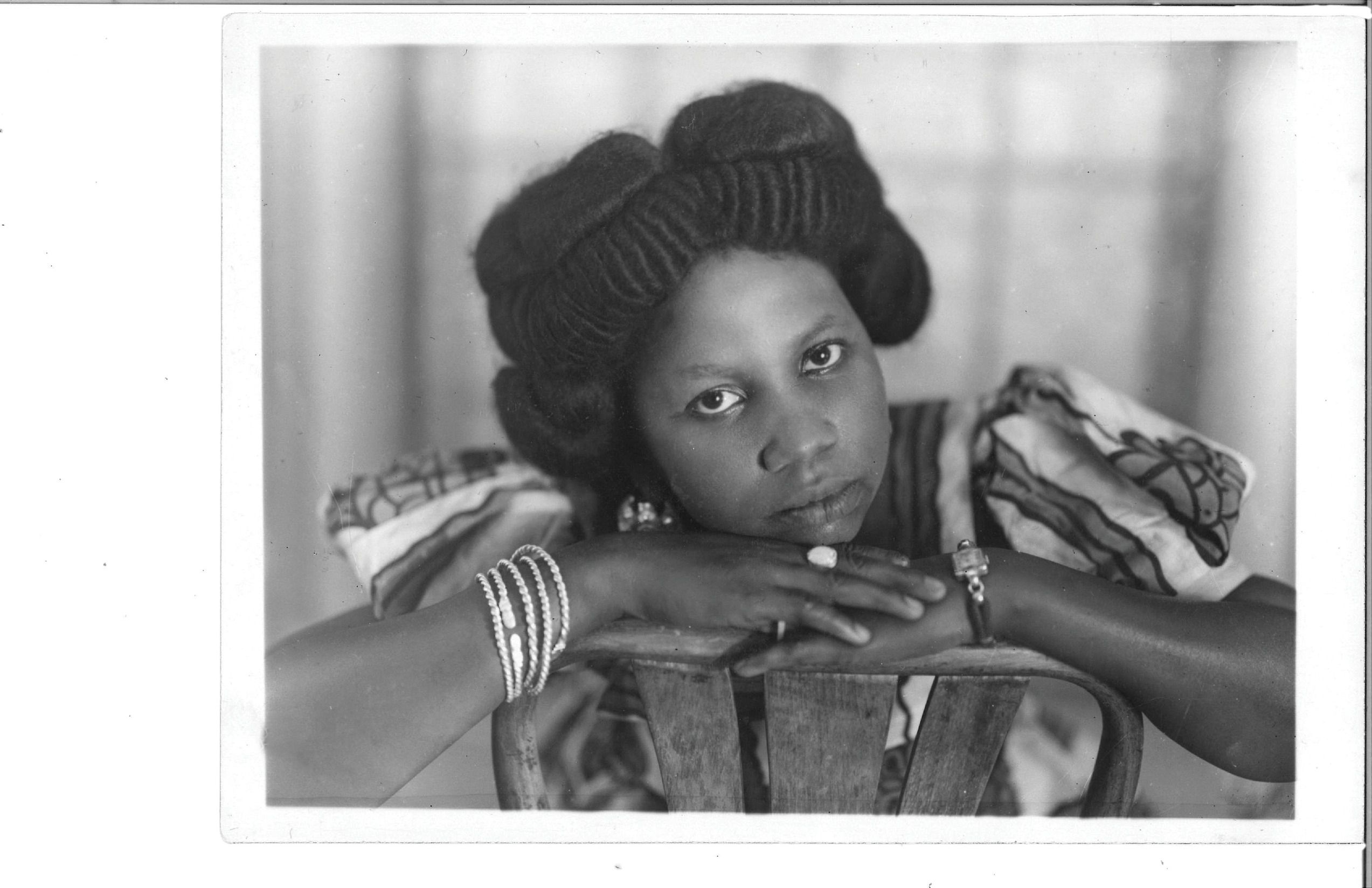

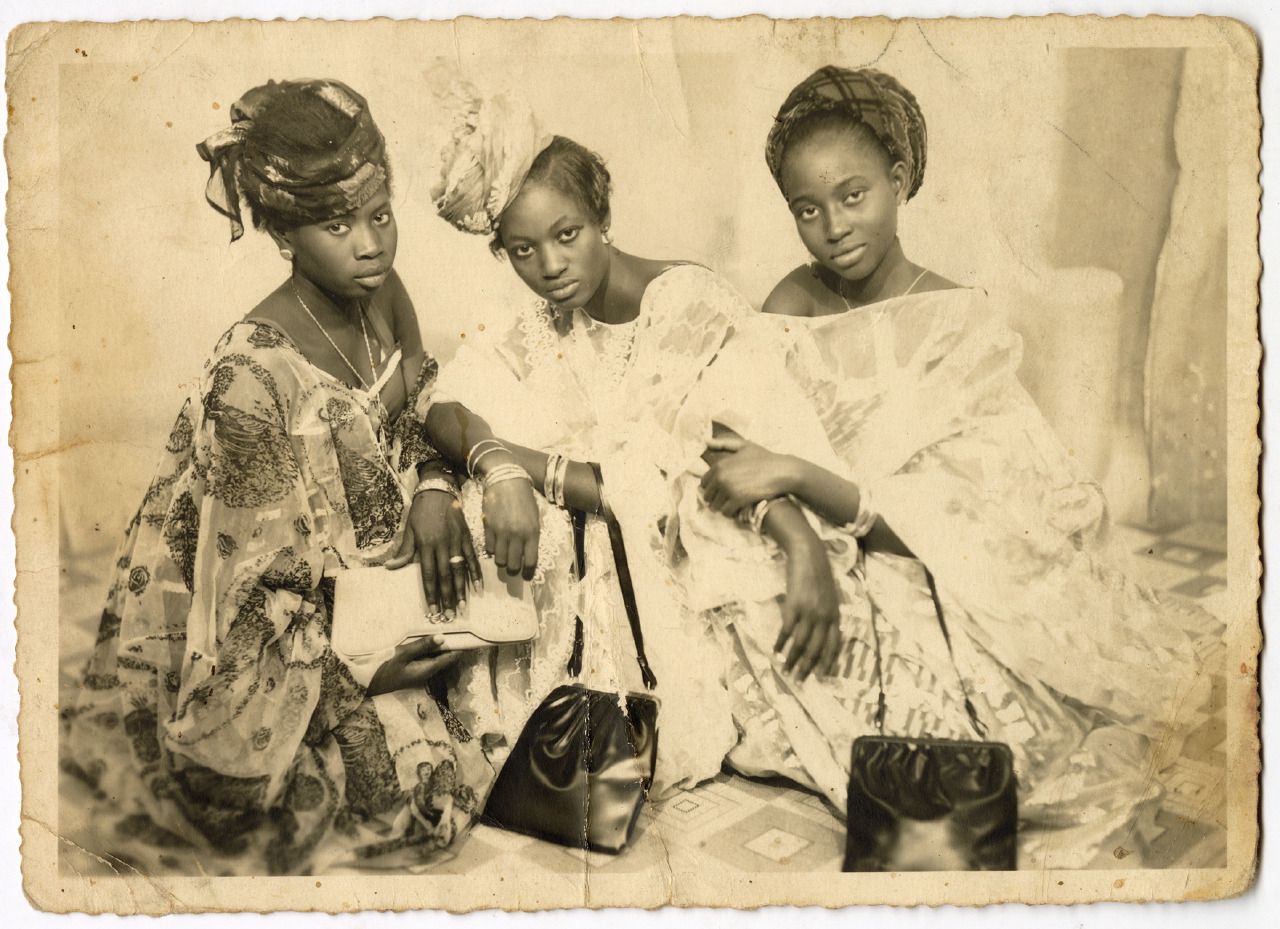

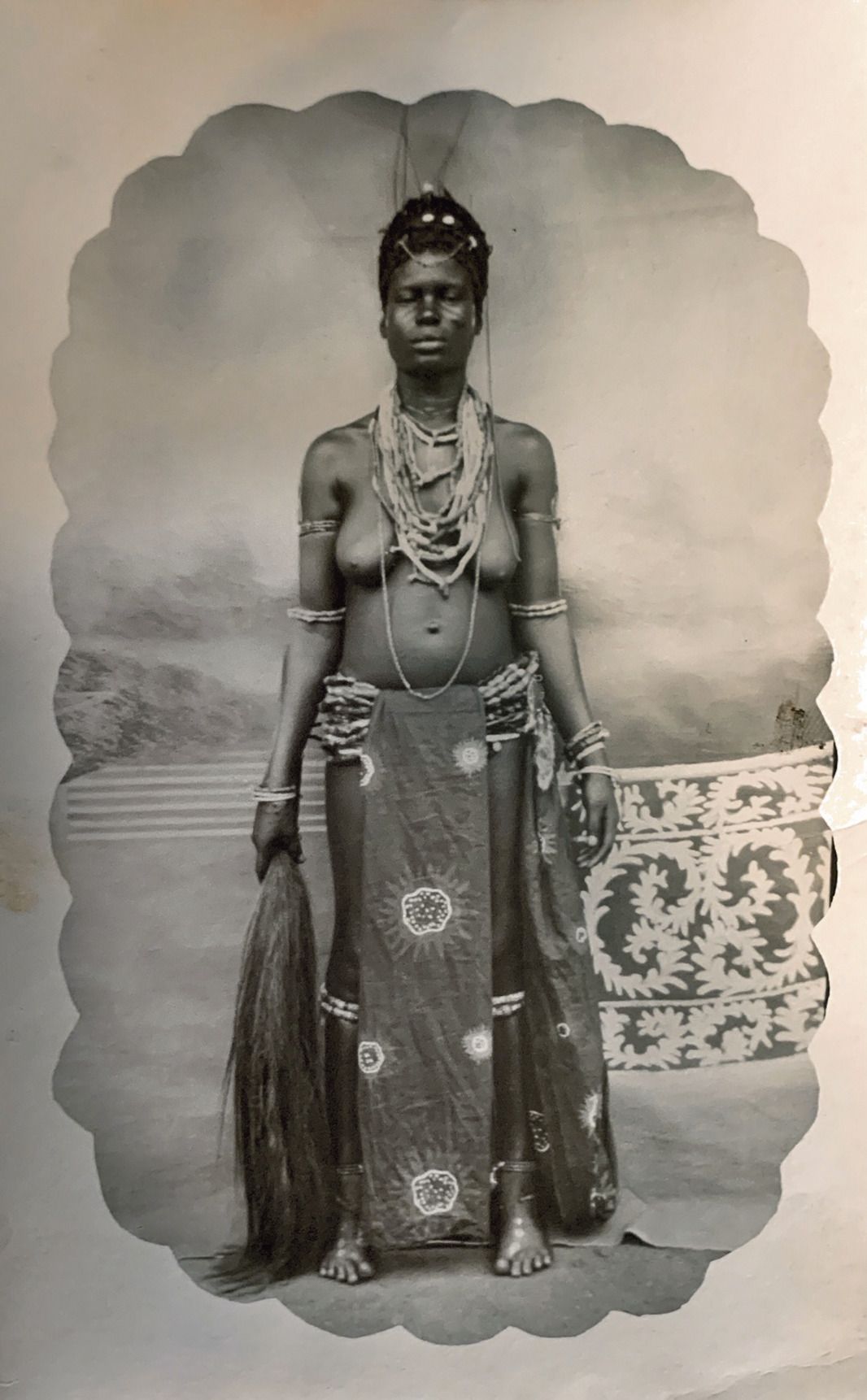

Her latest book, The African Lookbook: A Visual History of 100 Years of African Women, is a stunning collection of 150 studio photographs captured between 1870 and 1970. Following the Atlantic coastal trade routes of West Africa and along the Sahel from colonial to post-colonial and independence days, McKinley’s archive traces the Black African female experience of subjugation and agency primarily through the lens of African photographers, and a few European photographers and anonymous artists. Undergirding the images is the power and role that cloth and textiles have always had in both the African economy and in women’s personal lives; possessing fabrics and making and designing one’s own clothes were acts of self-empowerment, as well as creative expressions of self-adornment.

Featuring an introduction by the internationally acclaimed novelist Edwidge Danticat and a foreword by the award-winning novelist and memoirist Jacqueline Woodson, the book is a beautiful invitation to engage in visual conversation with the portrayal of Black African women through time.

Over Zoom last month, I had the enriching opportunity to speak with McKinley, Danticat, and Woodson about African women and ancestry, the power of photography, and the overlap of sewing and story making.

What in each of your minds is the main question at the center of this collection of images, and what answer do you hope it might offer?

Catherine E. McKinley: The collection is made up of so many interconnected things. But really, it comes back to our relationships with ourselves and those who came before us. I grew up, as an adopted child, without a lot of the obvious things we think of with inheritance. My father is Black, but my mother is Jewish, and there’s no Black ancestry on her side. I have this unbreakable need for this mother figure, which I’m sure had a lot to do with putting the book together. So for me, this project was somewhat about that— inheritance, a search for our foremothers, and likewise for ourselves. Keeping this archive over the years, and this intimate caretaking of the photographs has also been an act of caretaking of ourselves, of those other women [in the photographs], and of Black women globally. This project is really an act of love.

Jacqueline Woodson: So many African-Americans have been disconnected from our African heritage, but our voices are African voices of the diaspora. One of the answers I find in the book is related to my connection to these African women. Thankfully, because of DNA testing, I know that Nigeria and Ghana are where my ancestors came from. The Middle Passage and white colonizers at the time did a really good job of making us feel disconnected from that history and those ancestors. As ancestral people, we were left just kind of floating in the abyss. When we think about how much was lost with the slave trade, how many people were lost, I do feel like there’s this way in which we are constantly seeking our ancestors. We are constantly trying to figure out who we came from, and how we got to become who we became. So for me, going back to the African Lookbook and seeing so much of myself on those pages, it’s connected to something so much older and deeper than myself in America.

Edwidge Danticat: For me, it’s a compilation of heirlooms that embody both memory and agency. Yes, central to this book is that global connection of ancestors, but it’s also about self-presentation as preservation. The book travels through various moments and degrees of agency of these women. It takes us through moments of lack of agency, where these images were not self-directed, but rather were forced, and then traveled the world without the permission of the subjects. And then, it takes us through moments when women would walk through the studio in their most beautiful outfits and fabrics, and they’d choose to create an image for prosperity to pass on. We take images for granted. They are so abundant now that we can’t imagine the amount of effort it took to create some of the images in this book. Some were made against people’s will or knowledge, but others were images that they framed themselves, that they prepared themselves for, they dressed and paid for, because they considered them treasured objects. So, really, I feel like we’re being granted those images as gifts. They were meant as heirlooms.

Why do you feel it is important and valuable to showcase a history of images of African girls and women in this particular historical and cultural moment?

JW: We are in such a tumultuous moment, which really isn’t new for people of color in this country, but for me, this book is a balm. It’s saying to me, you’ve survived. Your images have survived. Your being has survived, and those who came before you are still with you. And these popular selfie images now of big butts and the duck lips the girls have, where does that sense of what’s beautiful come from? I mean, even as this country tries to erase Blackness in this way, here it is coming up again [in these trends]. You can’t kill the spirit. This is a book for now, but it’s also incredibly timeless.

ED: I think we also tend to freeze our elders in a certain way in our minds. For me, when I would go to my family albums, I would see my aunts in their ’60s outfits and their miniskirts, and I couldn’t believe that these were the same women. In the same way, I see my daughters now, and every time a new fashion trend comes up, they think they’ve invented it. So in part, I think the gift and value of opening a book like this is that the younger generation can see that “Black Girl Magic” has always existed. It’s always been here in some way.

CEM: And artistically, in terms of the photos and their history, there’s been an exposure to African photography over the last few years and we’re starting to get past the superstars of the field. We know about people like Seydou Keita, Malick Sidibé, and James Barnor. They are cemented in the canon. But now, other photographers are coming to the forefront. Plus, the art world is slowly starting to break down that monopoly held by white men, and in this case with African photography, it’s mostly been a few European men who controlled the entire narrative and the photos. Images like these are objects of the people, and we’re having more and more necessary conversations of decentering the art world. Valuable art doesn’t always have to be high art.

JW: That is what I love about the way you hold art, Cathy. It’s not like you’re collecting these images to go sell them at a higher value somewhere. What you’re saying is, “These images are for the people, and I want to find a way to get them into the gaze of the people.” When you see the way Europeans have controlled these images, it goes back to enslavement, except now it’s more of “We don’t have actual Black bodies, but we have their art that we can sell.”

The book highlights the sewing machine and the camera as tools of agency for women. What have these two instruments allowed African women to do in the last 150 years that has shifted private or public narratives?

CEM: Cloth held an extremely valuable place throughout the entire arc of colonialism. It was between 40 and 60 percent of imported goods. You look in the registrars, and there was an exchange rate of one body for two yards of cloth. You see those kinds of records over and over again. But for African women, it was also a viable way for them to hold economic power in what were traditional patriarchal systems. For example, in marriage, your dowry included a certain kind of cloth, and the value of it never changed. So that was a form of wealth for women. It was more stable than paper money. A woman could sell the cloth or hold it as an asset. And if you were able to trade and you were lucky to build wealth, that was probably the most likely arena for a woman to amass wealth.

The sewing machine was similar in that it was a surefire way to make stable money. A woman could even rent out her sewing machine. And if her husband was obligated within a month to give her a certain amount of cloth as part of her household allowance, then what she did with it was out of his control. Textiles have always been the arena where women had the most power. Sewing machines eventually became a dowry item, so it was another way to undermine the ways women were losing power through marriage. You hear women who were dyers or seamstresses who were able to leave a bad marriage because they had that tool. You could put the sewing machine on your head and leave.

JW: Again, learning about that ancestral connection, how a sewing machine could shift a woman’s story, is really powerful. It’s empowering. So much of the work that Black women were able to do at a certain historical time was domestic work, and with that domestic work came a loss of our bodies. There was a lot of sexual abuse, with white men sneaking back into the house, and many ways that Black women were subjugated during that time. Sewing was an independent activity. You were safe in your home doing it. You were creating something that would boost you economically. So many people coming out of that pain of enslavement, of domestic work, of being undervalued, and underserved, to get to this place of power and to create something beautiful … I’m sure it was very healing to some extent.

But as a child, I had no context for it besides that it kept me away from play. And there was a deep shame in it, in the same way that as a child, there was a deep shame to being connected to Africa. I personally love sewing now. I get into my sewing zone and I’m gone. But also when I’m writing, sewing is a way for me to work out plot and narrative in my head without being in front of my notebook or my computer. I’m still piecing stuff together and trying to make it fit into some kind of pattern, but it’s on the cloth first. And what eventually happens is that I figure it out on the page.

But the sewing machine is also connected to my mother’s narrative. When I was taking those sewing lessons as a child, my mother saw it as a way out. If nothing else, she reasoned, you could either do hair or be a seamstress. Coming from the South during the Great Migration, that was her idea about how you could survive economically in the new world. And to see, with these images and this book, that even that internal knowing comes from something older and deeper truly blows me away.

ED: My mother was a seamstress. We had a big sewing machine that was a hundred years old. Before she left Haiti and we were separated, she made me a bunch of dresses in bigger sizes so that I would have some dresses to grow into when she was gone. Then, when I moved to New York, she kept making my clothes, and I remember hating that so much. Now, I wish I had some of those dresses. But we would go into a store, and I would admire a dress, and she would feel it, and go, “No, this is too cheap. The material is bad, I can make it.” Something I now say all the time to my own kids. Yet back then, I was always miserable in my homemade dress.

Now, my girls are trying to sew. They have a dressmaking project with pillowcases, so we got a machine. Once, I was on a trip with my mother, and she ran out of clothes, and she literally took the pillowcase in the hotel and made herself a skirt. And here we are, my girls and me, making dresses out of pillowcases—it felt like such a circular thing. I didn’t appreciate it then but having that quick expertise and the ability to solve her problem, I felt she was powerful in that way. Sewing was very healing for my mother. When she would struggle, she did it. When she was sad, she did it. You would just hear the peddling of the machine. I think there’s lineage in it somewhere, to see how something affected someone, how it calmed them. Even if you’re young, you can see how if something has a powerful effect on someone you know, it’s something you want to emulate.

CEM: There’s also what you were saying before, Edwidge, about self-presentation as preservation. In a sense, I think about how many women in their work lives, particularly in places where secondhand clothing is so prevalent [speaking of bend-down markets common in parts of Africa] and much cheaper now than sewing, so people buy these clothes and wear. For instance, all over, say, Ghana, these women are wearing secondhand socks and a skirt for, like, their workday wear. It can be so abject sometimes, that the idea of then being able to make something for yourself at home on a machine takes on even more significance. Or just how people transform themselves, wearing their best for Sunday or for a funeral. I mean, it’s really beautiful and beyond powerful to know some women in a certain way all the time, and then the occasion comes where they dress up, and they become this other person.

In the Introduction, Edwidge opens with considering “how momentous a single photograph can be.” How, in your personal histories, has the photography and imaging of women made an impact on how you understand yourselves as Black women and in the work you each do as storytellers?

JW: Growing up in a family that was working-class poor for many years, we didn’t have a lot of photographs. Not even school photographs because some years, my mother couldn’t afford to buy them. I always thought people were really wealthy if you went into their house and you got to see all their photographs displayed on the wall. In white people’s houses, there was this lineage on the walls that we just didn’t have. So I became the keeper of all the photographs, the ones of my siblings and everything. I don’t want them to get lost again. My memoir, Brown Girl Dreaming, is about my story ’til I was 10 or 11, and at the back of the book, there are all these black-and-white photos. My aunt’s a genealogist, and she helped me cull some of the photos and family history. She was the one who sent all those pictures to me, and suddenly, I had this lineage, had my grandmother and my great grandmother on my father’s side, and I had my aunts and uncles and the people I had not known or seen pictures of. For me, putting those in the book was about realizing that I existed in this other way. It felt really triumphant to say, “Here is what I have, this is what I know now.”

ED: We didn’t have that many photographs either, and each one was special. We had a photograph of my grandparents on their wedding day. And as a child in Haiti, for every photograph I took, I had to go to a studio, and they were made for my parents in the States. Once I moved to Brooklyn, when we got class pictures, we blew up the proofs because the prints were so expensive. Once we were all grown up, my mother, on her birthday, would go and sit in a studio to have her photograph taken. When I gave birth to my own children, and she was here with me, she made us all go to a guy here in little Haiti who had a studio. She made sure each time we sat for a proper photograph. She didn’t trust the casual pictures we were taking. I bet it was something carried over from her childhood, where posing for photographs was even more rare. We have no photographs of her from her childhood. The youngest we have is when she’s in her 20s. But towards the end of her life, we have her sitting for portraits in her best self-made dress.

The types of images in this book make you see yourself in other Black women, so when I opened the book, I was like, “That could have been me, that could have been my mother or my aunt.” You could also see yourself back in time, or see these images as stand-ins for what you could have been.

CEM: I don’t have any photographs until I’m a year old because of my adoption. On my biological father’s side, there is no living female relative, and we don’t have any photos. It’s a huge absence, I can’t find any image of any Black woman of my direct bloodline in my family narrative. I’m also this fair-skinned woman, and I hated people questioning, “What’s your right to all this stuff?” It made me so furious, and it was painful to not be able to back it up with something. I used to think that this was insanity, but when I was a teenager, I’d walk around and look for Black women and take pictures of them, or if there was a flea market and there was a picture of Black women, I would keep the photograph.

When I went to boarding school, it was the first time that nobody knew anything about me. They didn’t know I was adopted. So I put all these pictures up in my dorm room, and I was like, “This is my mother.” Of course, I had to undo all that storytelling later on, and it was painful. So for me, curating this book is also about wanting to break the walls of colorism, of class, and of all these boundaries that we set up for ourselves.

Source: Read Full Article