Let’s not mince words: “Jazz Fest: A New Orleans Story” is a high-stepping, hand-waving, spirit-lifting gas. Co-directors Frank Marshall and Ryan Suffern, with the invaluable assistance of editor Martin Singer, have fashioned an infectiously exuberant overview of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, the Big Easy’s unique and enormous celebration of its music, cuisine and multiculturalism, by combining their own footage of performances and interviews at the 50th iteration of the star-studded annual event — the last before COVID-19 forced cancelation of the 2000 and 2001 editions — and archival footage dating back to the festival’s earliest days.

Those days might have begun earlier, fest co-founder George Wein reveals during an interview conducted before his 2021 passing, if he had accepted a 1962 invitation by locals to establish the New Orleans equivalent of his Newport Jazz Festival. But no, Wein, a white guy married to a Black woman, didn’t see how a “Jazz Festival” could be conducted in New Orleans during a period of Jim Crow laws and racial discrimination. It took nearly a decade before Wein was ready to partner with Allan Jaffe of the Crescent City’s Preservation Hall and get the party started.

That frank acknowledgement of the bad old days early in “Jazz Fest” is counterbalanced by almost everything that follows in a documentary that emphasizes at every opportunity the inclusiveness of New Orleans in general and the festival in particular. Aptly described by one interviewee as “the world’s greatest backyard barbecue” where just about everyone is invited, the event evolved by 2019 into a sprawling social gathering at the city’s Fair Grounds with 7,000 musicians performing on 14 stages over eight days. Peak attendance: an estimated 100,000 people on a single day, a number that would make it the sixth largest city in Louisiana.

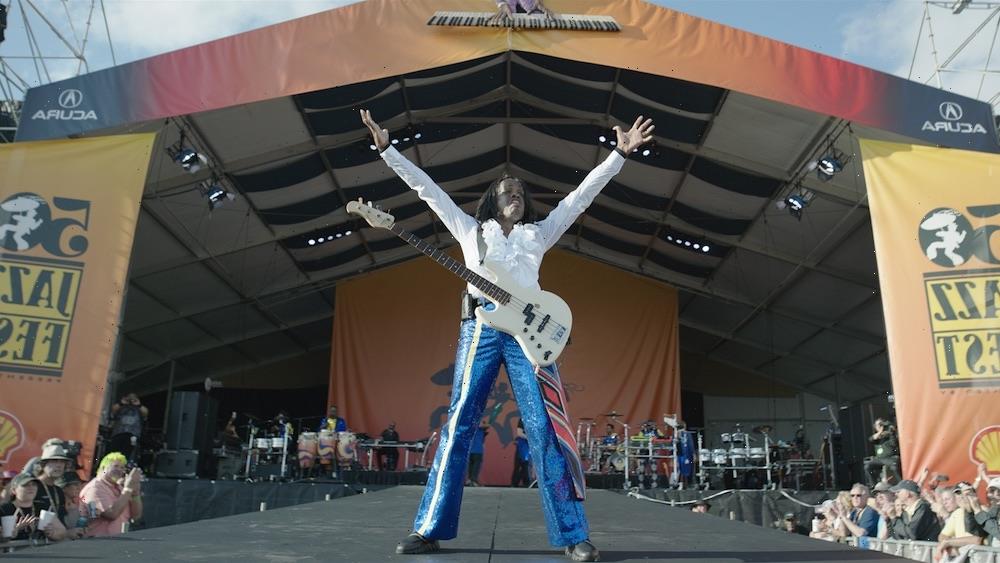

Among the stellar attractions represented by lengthy performance excepts: Earth, Wind and Fire (kicking off the event, and out the jams, with “September”), Irma “Soul Queen of New Orleans” Thomas, Pitbull, Jimmy Buffett (who claims musical roots in New Orleans, and is credited as a longtime festival draw) and Gary Clark Jr. Mind you, these are just a few of the household names. Festival organizers cast their net wide to accumulate a lineup of homegrown, national and international artists ranging from the Crocodile Gumboot Dancers of South Africa and 3L ifbed of Benin to New Orleans “bounce music” queen and spiffy dresser Big Freedia and Trombone Shorty & Orleans Avenue.

The singer-songwriter known as Boyfriend — who seems at once amazed and amused that she’s able get away performing with her all-girl ensemble on the Jazz Festival stage in hair curlers and lingerie — enthuses about sampling the horizon-broadening variety of music while traversing from tent to tent, stage to stage, and says that, one way or another, “You’re going to experience something that your computer would never put in your feed.”

As one of the most memorable show-stoppers in a show with more stops than a downtown bus, Katy Perry harkens back to her gospel roots with a vibrant rendition of “O Happy Day” with the Gospel Soul Children of New Orleans, then segues, still accompanied by the choir, into her own secular empowering anthem, “Firework.”

Typical of the diversity on display: Herbie Hancock’s bop “One Finger Snap” is followed by Samantha Fish’s blistering “Bulletproof,” and in turn is followed by Sonny Landreth’s spirited take on the traditional “Walking Blues.” At another point, jazz legend Ellis Marsalis Jr. offers a rare performance with his sons — Wynton, Branford, Defeayo and Jason Marsalis — and jovially expresses gratitude for still being remembered at his advanced age: “It’s nice to be wanted without being in a picture in the post office.”

“Jazz Fest” periodically ventures beyond the Fair Grounds to offer a more complete picture, traveling to Southwest Louisiana to explain to the uninitiated the difference between Cajun and zydeco music, and referencing Mardi Gras to underscore the distinction of New Orleans being the only city in the United States where students in high school bands can routinely expect a chance to shine in carnival season parades. And take heed: There are enough loving closeups of the mouthwatering and cholesterol-loaded Louisiana dishes for sale throughout the Fair Grounds that you may feel your arteries hardening just from watching.

Snippets of context-establishing history lessons are generously sprinkled throughout the film — the filmmakers respectfully connect the dots between music played as entertainment by slaves and the distinctive sound of New Orleans jazz drumbeats — though some viewers might wish there was even more time devoted to, say, the fusion of Native American and African American cultures in the tradition of brightly bedecked Mardi Gras Indians strutting their stuff at the festival.

On the other hand, the final scenes of “Jazz Fest” affectingly concentrate on history of a different kind, the 2005 devastation of New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina. In the wake of epochal flooding and destruction, some thought there couldn’t be a 2006 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. Some thought wrong. In Spring 2006, the festival not only survived, it thrived, drawing crowds that surprised even fest organizers and showcasing Bruce Springsteen as he seized the moment with a stirring performance of “My City in Ruins.” Springsteen claims in an on-camera interview that he actually was scared before performing that particular song to that particular crowd at that particular moment.

If there’s anything to complain about “Jazz Fest: A New Orleans Story,” it’s the brevity of the film, the obvious winnowing of the 2019 artist lineup — Tom Jones appears only fleetingly in interview clips —and the frequent interruption of performances by interviews. There doubtless will be additional material available in future special-editions, but that’s not quite the same thing as being able to sample everything now during a theatrical release. To paraphrase an admonition from a classic Rolling Stones album: This movie should be played real loud. And in venues where people can, if they choose, get up and dance.

Source: Read Full Article