Pete Davidson on Saturday posted a troubling message on his since-deleted Instagram page that led to concerns about his well-being. “i really don’t want to be on this earth anymore,” he wrote. “i’m doing my best to stay here for you but i actually don’t know how much longer i can last. all i’ve ever tried to do was help people. just remember i told you so.” The note prompted a well-being check by police and an outpouring of support from other celebrities, including Davidson’s former fiancée, Ariana Grande. He was found accounted for on the set of Saturday Night Live and briefly appeared on that evening’s episode to introduce musical guest Miley Cyrus, but the note put mental health awareness and online bullying front and center.

As far as spectacle goes, the image of Kanye West embracing Donald Trump in the Oval Office this past October fell somewhere between the Krispy Kreme backflip Vine and the series finale of The Sopranos. It was confusing. It was compelling. It was unhinged. It was, in short, irresistible. The rapper’s widely broadcast ten-minute soliloquy was as rambling as it was enticing, touching on everything from male energy to Montessori to the 13th Amendment. West in the West Wing was the perfect storm of celebrity, power, and—for lack of a better word—content. You would not be alone if you periodically said, “Man, he’s crazy!” as you watched.

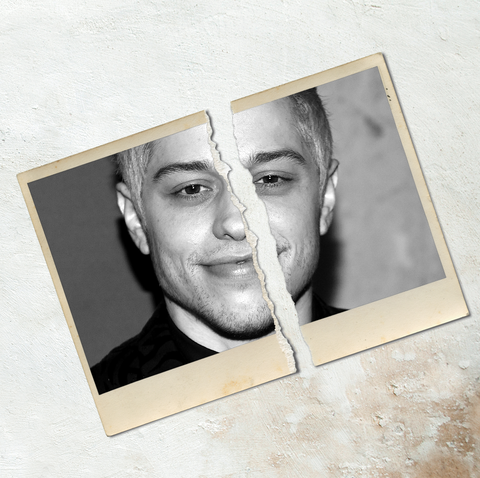

Getty Images

And you wouldn’t be wrong, either. In fact, you might be a little too right. West, who not too long ago discussed his diagnosis of bipolar disorder with the world, joins a list of celebrities who are open about their struggles with mental health and also struggle with their mental health openly. They include SNL’s Pete Davidson, who courageously (and hilariously) mined his borderline-personality-disorder diagnosis for material before engaging in a public, brief, and somewhat torrid love affair with Ariana Grande; Tesla cofounder Elon Musk, who tweeted about the corrosive effects of stress on his mental health even as he bore those out in a series of ill-advised (and possibly illegal) tweets about his company; and Roseanne Barr, who was diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder years before she sent a racist tweet in May that scotched her comeback show. Their struggles have played out in the white water of popular culture, and it’s been a crazy ride indeed.

But when used to describe a person, crazy is halfway between a common adjective and an informal diagnosis. Toss it out with little thought and it’s fun and flirty. Think about it more—what it really means, what’s really going on when we say it, and what’s going on with those we say it about—and the word becomes heavier and heavier.

For the millions of Americans who, like me, live with mental illness, crazy is a heartbreaking and terrifying reality. Living in the tide pools of sanity, I can confidently say that whatever glimpse of crazy you catch in public is vastly outstripped by the private suffering you’ll never see. That’s the suffering that rends the fabric of primary relationships, that barges into the cockpit of the self and messes with the dials; it’s a suffering that doesn’t care if you’ve got a blue verified badge on Twitter, a sitcom, Yeezys, or millions in the bank. If you know what that suffering is like, there’s no way to just sit and watch a public meltdown with popcorn.

But that’s not to say we should simply look away, change the channel, or fasten ourselves to a different trending hashtag. Any of these episodes can be an opportunity to spur a genuine and much-needed discussion about mental health. Granted, this is a whole lot less fun, and it pries open a can of morally slippery worms. Does the fact that Roseanne has been diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder absolve her of her racism? Does the fact that Kanye may be bipolar render his opinions about minorities invalid? This conversation becomes even more difficult in light of the silence of mental-health professionals, who, bound by what’s called the Goldwater rule, are barred from offering a professional opinion about the mental health of individuals they have not examined personally. Thus an illness goes unnamed and, in the silence, dangerous and dismissive confusion grows.

These incidents and others like them also provide an opportunity to develop empathy. You don’t have to suffer from mental illness like I do to have compassion for those who do. There’s a Buddhist practice, meant to foster loving-kindness for all creatures, in which one visualizes that all sentient beings were, at some point, your mother or will, at some point, become your mother. Now, you might have a complicated relationship with your mother—I know I do—and you might not believe in rebirth. But that way of thinking, of considering another person as a loved one, even for a second, is like catching a glimpse of a set of keys that fell into the sidewalk grate. It’s heartbreaking. It’s eye-opening.

Ultimately, no one can deny the brilliance of the sparks as someone—especially a high-profile someone—runs off the rails. Such a spectacle will never be ignored and probably shouldn’t be. But try not to marvel at the sparks and then ignore the passenger in danger. What’s there isn’t just a celebrity self-immolating but a person suffering, too. Take it from one who has also suffered. Crazy deserves our compassion, not just our clicks, and we owe it to ourselves to see through the spectacle to the human—on both sides of the screen.

Source: Read Full Article