Though it sets out on a ghost hunt, Adrian Sibley’s fitfully fascinating documentary works better as an exploration of its subject’s public and private personas, charting Richard Harris’ rise from local sports star to screen legend via an unexpected heyday as a chart-topping pop star in 1968.

Rather than start with a séance, however, The Ghost of Richard Harris, screening in the Classics section of the Venice Film Festival, opens with the more prosaic sight of the actor’s three sons — Damien, Jared and Jamie — going through their late mother’s lock-up, where they find journals full of poetry, King Arthur’s crown (a prop from 1967’s Camelot) and trinkets from the Harry Potter franchise, in which their father played Dumbledore until his death in 2002, aged 72.

This set-up proves to be somewhat self-defeating, as the three middle-aged men, while reminiscing, then admit that they were packed away to boarding school for some two-thirds of their childhoods — pretty much the exact periods when Harris was at the peak of his artistry and in the prime of his hell-raising (a term coined by British tabloids almost exclusively for Harris and his drinking buddies Peter O’Toole and Oliver Reed).

Happily, though, this is not a family whitewash, and Sibley’s film is refreshingly gung-ho about Harris’ carousing: in interviews, the actor is heard to be unapologetic about his drinking, drug-taking and womanizing (with the now-familiar caveat that this was “a different time”), and he even claims that — for an artist — personal demons are actually a gift to be embraced for inspiration rather than sins to be cleansed.

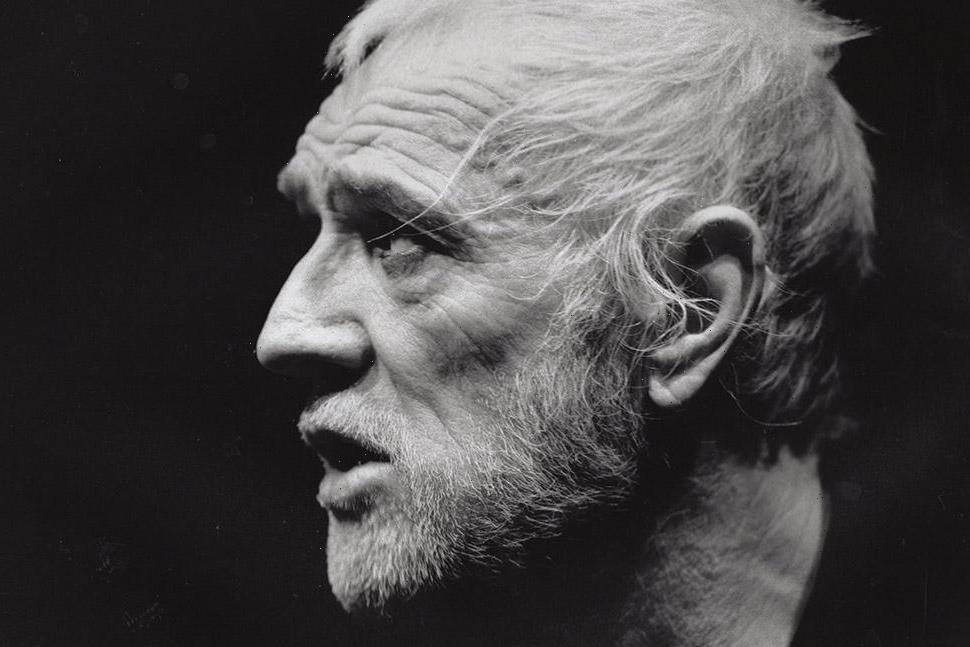

This, to be clear, is the public Richard Harris talking, the man who shot to fame after starring in Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life (1963), part of a new wave of realist cinema that gave voice to working-class actors from the UK (and, in Harris’ case, Ireland). The private Richard Harris, known as Dickie back home, was a less arty beast, an avid swimmer and sports enthusiast whose only real regret was that he didn’t get to play rugby for his homeland. Sibley’s film delves into this supposedly hidden side of Harris’ life, but even the most colorful nuggets aren’t all that revealing — and, for some strange reason, one of the film’s biggest insights is left to the end, explaining that a childhood bout of tuberculosis was what killed off those sporting ambitions for good.

Equally curious is that Harris’ big-screen outings are a little less celebrated than his early stage work, which, admittedly, was more impactful and a hell of a lot more focused than his casual demeanor would suggest. The game-changing musical Camelot, of course, gets a lot of attention, but Harris completists might want more mention of, say, 1970’s A Man Called Horse, or 1974’s Juggernaut, although any oversight about his talent is corrected in a whole section devoted to Jim Sheridan’s The Field (1990). The latter brought Harris his second and last Oscar nomination after This Sporting Life — not a bad achievement for an actor who claimed he never played the Hollywood game even after being filmed and photographed at parties and awards ceremonies doing exactly that. But then, Harris was never a man to abide by anyone’s rules, especially his own.

Two remarkable sequences lift the film above what you might normally expect from a TV arts show, which is what this basically is. The first is the retelling of Harris’ “lost week” — actually a planned and well very documented event that was gifted to the actor for staying sober during the shoot of period drama Cromwell (1970). The boozy images of Harris and friends passed out in the streets of Paris and dancing in a German brothel put to shame the antics of any contemporary rock or pop act. And speaking of which, Harris finally gets his due as the motivating force behind “MacArthur Park,” the easy-listening 1969 epic written by a then-unknown Jimmy Webb that became a huge hit with its teasing flirtation with the LSD/hippie culture of the day in the famous line about a mysterious rain-sodden cake and “the sweet green icing flowing down.”

Interest is likely to be niche after its festival bow at Venice, but The Ghost of Richard Harris is a valuable reminder of a time not just before the cancel culture of today but the era of strict PR control that immediately preceded it. Harris would have scoffed at both, but then he was always an immaculate self-publicist, keeping a tight rein on his supposedly contradictory identities as “Richard” and “Dickie” and always mindful of the media’s choppy waters. As the actor says himself, in a clip from his lauded 1990 version of Pirandello’s Henry IV: “Woe to him who doesn’t know how to wear his mask.”

Must Read Stories

‘The Rings Of Power’ Aftershow: Eps 1 & 2; Amazon Reveals Record Ratings

Summer Wrap-Up: Chaos Isn’t Reigning With $3.35B+ Take Despite Exhibition Woes

Red Carpet Restrictions Frustrate Press Agencies; Chalamet Fever; Reviews: Full Coverage

Chris Rock Slams Will Smith’s “Hostage” Apology Video During London Show

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article