How many DIY filmmakers can shoot footage so arresting in composition and content that it could fit seamlessly in a Steven Spielberg movie? Underwater documentarian Valerie Taylor and her husband Ron did just that. The Australian filmmakers captured the footage in “Jaws” of a great white shark mauling the diving cage that supposedly held Richard Dreyfus just moments before, its powerful body thrashing against its metal bars with unrelenting destructive force. The message to the world was clear: not even steel could stop a great white on the hunt.

That’s a message Valerie Taylor, now 85, has been trying to dispel ever since. It’s a regret Australian documentarian Sally Aitken captures in her new film about Taylor’s life, “Playing with Sharks,” a NatGeo-ready documentary that mixes some of the most beautiful images you’ll ever see with a talking head-filled structure too pedestrian for so extraordinary a subject.

An achievement in editing together superlative archive footage, “Playing with Sharks” owes its beauty almost entirely to Valerie and Ron, who was usually the one behind the camera as this husband-and-wife team dove into coral reefs, kelp forests, and all manner of shark breeding grounds. Ron, who died in 2012, is the first credited cinematographer of “Playing with Sharks” (out of five total listed), which seems only fair. He and Valerie married in 1963 after meeting on Australia’s competitive spearfishing circuit, a hyper-macho milieu where male hunters outnumbered women 100 to one.

Valerie, still radiating star power, appears on camera in the present as she prepares for a diving trip to Fiji, and she’s as full of daring and passion for the briny depths as she was more than half a lifetime ago. She talks frankly about how she too was scared of sharks when she first saw them on her dives way back in the 1950s — and she speaks with regret about killing one large nurse shark on-camera for a black-and-white underwater film. It’s easy to see how Australian media at the time would have presented her, with her self-made bikinis, as a kind of Bond girl of the deep in pursuit of the scariest “big game” of all.

But Taylor and her husband quickly abandoned her spear gun for a movie camera. What one of the talking heads — among whom are shark lover and shark attack survivor Rodney Fox and “Jaws” author Peter Benchley’s widow Wendy — alludes to is something Aitken might well have focused on a bit more: how it is that hunters often become the most committed conservationists. It’s a missed opportunity that speaks to a larger issue with Aitken’s film. Just like you need a line to reel in a great fish, you need a throughline on which to hang your film, especially one built so extensively on decades-old footage shot by others. Aitken never quite finds that throughline, other than just her obvious pie-eyed wonder at Taylor, a reverence that almost interferes with us seeing her for who she really is and not just as Aitken sees her.

Maybe that’s harsh criticism for a movie that has more wonders on display second-by-second than most others you’re likely to see this year: but that is due entirely to the footage Taylor, her husband, and their small circle of collaborators shot themselves. Sometimes sharks swim directly into their camera, bumping their noses on the aperture. Valerie has a tête-à-tête with a group of seals lounging on rocks underwater as if they were above the surface. She swims through giant walls of kelp and through school of bright pink jellyfish. She hand-feeds a great white shark. It’s like “Planet Earth” as home movies, which makes for nature cinematography that’s quite singular.

While most of the 4K-ready nature documentaries you’d see from the likes of David Attenborough and the BBC Natural History Unit emphasize the otherworldly nature of the animals on display, and cuddly, kid-friendly efforts like “The Elephant Queen” seek to anthropomorphize animals until they’re “characters,” Valerie and Ron Taylor sought something in between: wonders that are matter of fact and human-scaled. Putting Valerie into so many of his shots meant that you get an accurate sense of the size of the creatures you’re watching. It also makes them somehow more “real” and thus all the more urgently in need of our protection.

Valerie Taylor in the work shop on Marthas Vinyard with “Bruce” the mechanical Great White shark, during the filming of “Jaws”

Ron & Valerie Taylor

Watching the Taylors’ footage is an act of time-travel in a sense, because so many of the glories they captured have now vanished: many of the coral reefs they swam through have died, and sharks themselves are profoundly endangered. That human-scale photographic approach they took lent itself perfectly to working with Spielberg on “Jaws.” Because the great whites the Taylors would be capturing on film were only 13 feet long and Spielberg wanted the effect of a 25-foot shark he suggested they use a half-size boat, a miniature protective cage, and a little person, Carl Rizzo, as a stand-in for Dreyfus in underwater long shots. An ingenious bit of forced perspective that added to an unfortunate legacy of the film: the demonization of sharks and a decades-long wanton disregard for the fact that they may actually be endangered, especially given the massive global market for shark fins (for soup and as trophies).

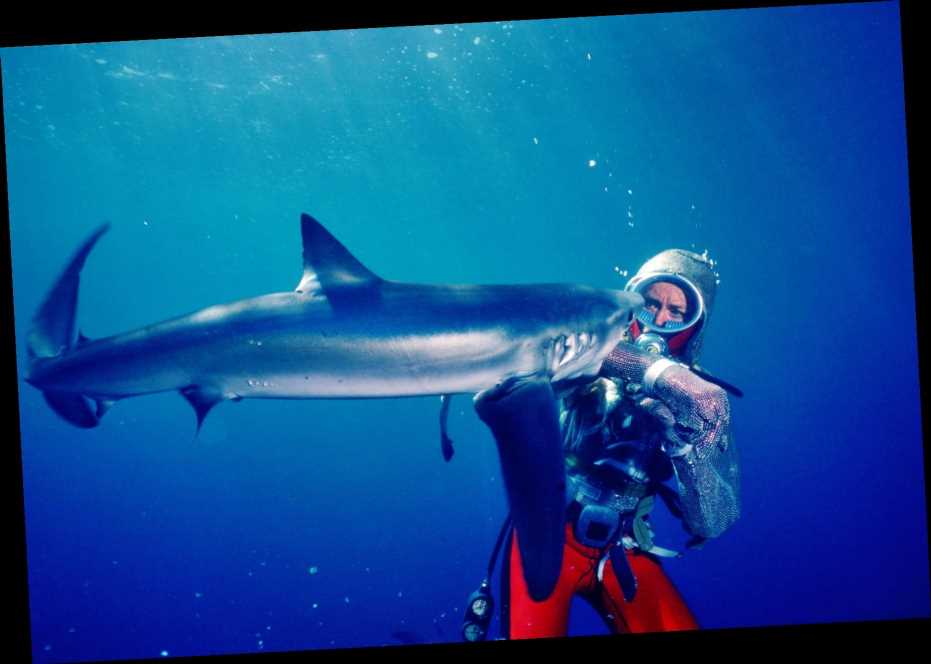

Taylor’s efforts to make sharks less scary ever since have included her development of a chain-mail suit to let sharks bite her. Most shark experts had thought they overwhelmed their prey with their jaws’ “crush power” — suggesting great whites apply thousands of pounds of pressure per square inch — while Taylor’s observations of their behavior left her to conclude they killed their prey by using a sawing-action with their teeth. So a chain-mail suit would protect her, even if she let a shark bite down full-bore onto her arm.

Even as an octogenarian in the moving final sequence of the film, which finds Taylor diving near Fiji, she wears a bright pink wetsuit. She’d been warned it would alert the bull sharks to her presence. But that’s exactly what she wanted.

“Playing with Sharks” plays a bit like the “Apollo 11” of this year’s Sundance: a film that mixes the magical and the mundane in equal doses — the crude animatics in that film, used to explain the astronauts’ journey through space, functioned like the talking heads do here. You wish there would be a more engaging storytelling device. Setting the Taylors’ footage in such a quotidian structure is like setting the world’s most beautiful diamond in a ring pulled from a Cracker Jack box.

Grade: B-

“Playing with Sharks” premiered at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival in the World Cinema Documentary Competition section. The film is currently seeking U.S. distribution.

Source: Read Full Article