For fans of cult television from yesteryear, the word “quantum” might evoke images of actor Scott Bakula bouncing around points in time with a holographic sidekick in the bygone NBC show “Quantum Leap.”

But quantum technology is not science fiction.

It’s real. And the next generation of that technology is slowly emerging from research labs into the commercial sphere right now. It’s early yet, but the technology has the potential to transform everything from chemical development to self-driving car technology to computing as we know it, backers and researchers say.

Amid all that buzz, Colorado, specifically, the Denver-Boulder area, is putting its stamp on the quantum realm. The area sports decades of research expertise, a pipeline of talent and a roster of ambitious companies aiming to make waves. It’s an industry concentration that could pay huge dividends for the state’s economy if the technology lives up to its promise.

“People call Silicon Valley Silicon Valley for reason. We think about it as the Quantum Front Range,” said Tony Uttley, president of Broomfield-based Honeywell Quantum Solutions. “It’s in its absolute infancy right now but at the front of something is going to be absolutely gigantic.”

What is quantum?

Quantum technology already impacts people’s lives on a daily basis, said Jun Ye, a physics professor at the University of Colorado and a fellow at JILA, a joint research institute between CU and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, or NIST, that has been at the heart of major quantum breakthroughs. (Note: Ye is also a fellow with NIST.)

It is used in cellphones, global positioning systems and medical devices, Ye said. The excitement percolating now is around what the physicist calls a “second quantum revolution.”

“We’ve had a good time working with individual particles when they are in a quantum state. Now we are teaching those particles to work as a team, what we call quantum entanglement,” Ye said.

When you have multiple quantum particles working together, it increases speed for computation and uses for science, Ye said. He uses quantum technology to build ultra-accurate atomic clocks.

“There are existing clocks we use to define seconds,” Ye said. “And the current clocks we are developing now already exceed the performance of those clocks by two or three orders of magnitude.”

If scientists can better harness quantum entanglement and mitigate “noise” in that process, Ye envisions applications like using quantum technology to control vehicles on Mars from Earth and providing more sensitive tools for measuring sea-level change and glacial melt.

“Quantum will continue to define the frontier of technology,” he said before adding a caveat. “In some cases, these computers are still very primitive. They are not yet powerful enough to do universal quantum computation.”

Alex Challans, of the Quantum Daily, an industry news site dedicated to making quantum technology more accessible and understandable, admits it’s not an easy topic to introduce to the uninitiated.

“You can’t explain this over a beer in the midst of a conversation because you will ruin the conversation,” he said.

The site has a detailed resource page covering terms and questions around quantum computing. When it comes to real-world applications, the Quantum Daily is preaching patience.

“We have been very cautious about companies that say that have new technology that going to change the world, We’re just not there yet,” Challans said. “If we are able to make quantum computers that are scaleable then it will be transformative.”

Like the early days of the internet

Boulder-based company ColdQuanta is jockeying to be at the forefront of the quantum revolution and it recently brought in a tech sector heavy hitter to help get it there.

Last month, the 14-year-old company named Dan Caruso its executive chairman and interim CEO. Caruso co-founded two internet infrastructure giants along the U.S. 36 corridor, Level 3 Communications and Zayo Group, the latter of which Caruso led onto Wall Street before taking it private again last year via a $14.3 billion sale.

Caruso likens the opportunities in quantum today to the early days of the internet.

“Commercialization is going to increasingly become commonplace beginning now and over the next handful of years,” Caruso said. “In 10 years, it will become prevalent across the board.”

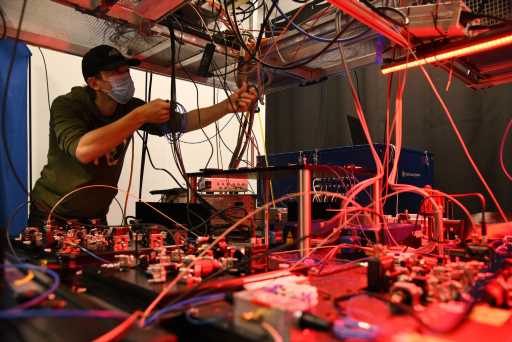

There are different ways to harness the power of quantum computing. Google uses superconducting loops for its quantum computer. Honeywell is focused on trapped ion technology. ColdQuanta, as its name might suggest, is focused on keeping things cold.

Using what the company calls the cold atom method, ColdQuanta builds off Noble Prize-winning work at JILA, to use lasers to super cool atoms, putting them in a quantum state. In the news release announcing Caruso’s hiring, ColdQuanta calls this method the “most scalable, versatile and commercial viable area of quantum.”

Caruso said the challenge before the company, already a strong research and development outfit with $50 million in research contracts and another $54 million in funding, is turning the technology into usable products. Getting there will take more capital.

ColdQuanta last month launched a fundraising effort, leveraging Caruso’s connections to bring in New York investment bank PJ Solomon to lead the ambitious round.

“My guess it is it will take multiple months to get to the finish line because we want to find the right investors who want to take this to the full potential that we feel is in front of it,” Caruso said. “We would like to get well north of $200 million.”

ColdQuanta is hitting the venture capital market amid a craze in quantum investing. The Quantum Insider, a sister company to the Quantum Daily that provides private and public sector clients with data and information on quantum technology stakeholders, saw quantum technology investment more than triple from 2019 to 2020, hitting $930.3 million last year. This year, through less than four months, Quantum Insider has already tracked $757.2 million in investment.

Related Articles

-

Colorado makes a bid for quantum computing hardware plant that would bring more than 700 jobs -

Boulder born and (still) based Zayo Group is a private company once more after $14.3B sale -

Record unemployment, massive bailouts, new businesses: Colorado’s pandemic economy is a shifting landscape

Just what commercial applications does ColdQuanta’s leadership foresee for its technology? In a slide deck for investors, the company looks beyond quantum computing to highlight quantum’s next-generation sensing abilities. Global position systems could be things of the past, replaced by much more advanced and accurate quantum positioning systems. Radar, lidar and medical imaging technology will be pushed aside by much more acute quantum sensing.

ColdQuanta sees noncomputing quantum technologies as a bigger share of the quantum technology pie already and expects it to be a $49 billion market buy 2030 compared to quantum computing’s $44 billion, according to the investor deck.

“You think of everything that requires sensing in different contexts,” Caruso said.

ColdQuanta co-founder and chief technology officer Dana Anderson (also a CU professor and colleague of Ye’s a JILA) explains quantum technology’s importance like this: In applied physics, doing something as well and as precisely as possible is known as operating at the “quantum limit.”

“In the future, if you aren’t operating the quantum limit, you won’t be competitive. Period,” Anderson said. “Quantum science from a scientific point of view is important. It’s fascinating. But from a business and applied sciences point of view, my view is quantum, even if it’s a little bit fashionable today, it will never go away.”

The U.S. 36 corridor as a quantum hotbed

Honeywell — widely know for their thermostats and smoke detectors — has tech expertise that goes well beyond the average living room, touching on everything from cryogenics to magnetic fields to high-precision control systems used by NASA, officials say.

When the company decided to dive into the quantum waters five years ago, it chose the U.S. 36 corridor between Denver and Boulder. It’s not a big secret why: expertise in the field driven by NIST and JILA.

“We’ve built an exceptional team of scientists and engineers and technicians and then an entire functional business staff to be able to go after the quantum computing space,” said Uttley, a former NASA staffer who leads the company’s Honeywell Quantum Solutions arm. “We have a really good relationship with CU Boulder and the Colorado School of Mines to be able to foster this pipeline, from our standpoint, our future talent that is coming in as well.”

Honeywell Quantum Solutions employs about 110 people in Broomfield and about 40 more in Minnesota, Uttley said.

The company is pushing into commercialization. It made its first quantum computer available to subscribing businesses in June of last year. Its second went live in September, Uttley said. Customers so far include JP Morgan Chase, BMW and Samsung.

“What we’re finding is there are certain industries that are very forward-leaning when it comes to quantum computing. One is financial services. And then a lot of chemistry,” Uttley said, noting quantum could provide an edge in new pharmaceutical and material development.

With a major player like Honeywell choosing to locate in Colorado and local companies like ColdQuanta striving to scale up quickly, Colorado is on the shortlist of places that could be the epicenter of the quantum industry over the next five to 20 years. But it’s certainly not alone.

Caruso pointed to the Chicago Quantum Exchange, touted by officials in Illinois as the nation’s first quantum startup accelerator. That could be a model for Colorado, said the ColdQuanta executive, who happens to be a University of Illinois alum.

“I think they are a step ahead of Colorado but we would like to help Colorado close that gap and get right up there,” he said. “It would be gigantic.”

Colorado economic development officials are paying attention. In February, the state’s economic development commission approved up to $2.9 million in state job growth incentive tax credits for a manufacturing plant that will produce quantum technology hardware.

“I think quantum presents a really unique opportunity for Colorado,” said Michelle Hadwinger, deputy director of the Colorado Office of Economic Development & International Trade. “In terms of the state, I think we are just getting started in terms of getting aware of the ecosystem.”

The state would be well advised to move fast. President Joe Biden’s massive infrastructure investment plan includes money earmarked for scientific research and development. Administration officials have called out quantum by name as a focus area.

Corban Tillemann-Dick is the CEO of Maybell Quantum Industries, the manufacturing company approved for that job growth tax incentive earlier this year. He is currently looking for space along the U.S. 36 corridor to relocate his company from New York state.

He says Colorado has the talent and quality of life to attract early-stage companies like his, but as quantum emerges and the dominant technology of the next 30 years the companies will follow the tax incentives and jobs will follow the companies.

“This is a civilization-shifting technology but it’s not there today so you’re going to need leaders with real foresight to say it’s cheap for us to invest now in the future of this technology rather than waiting for it to be established and scaled,” Tillemann-Dick said. “Then the power will shift entirely to the companies doing quantum.”

Source: Read Full Article