By Katherine J. Wu

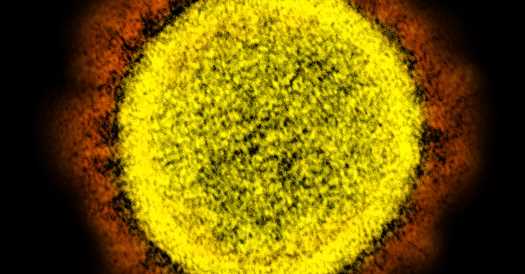

An overwhelming body of evidence continues to affirm that the coronavirus almost certainly made its hop into humans from an animal source — as many, many other deadly viruses are known to do.

But since the early days of the pandemic, experts have had to fight to combat misinformed rumors that the coronavirus emerged from a lab as part of a sinister scientific project.

Last week, yet another piece of unfounded and misleading prose entered the fray: a study, posted online but not published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal, contending that the virus is artificial and an “unrestricted bio-weapon” released by Chinese researchers.

My second scientific report is published in zenodo.

This is the only account in Twitter for Dr. Li-Meng YAN. pic.twitter.com/THgVjuQawx

The manuscript also baselessly denounced several parties, including policymakers, scientific journals and even individual researchers, for censoring and criticizing the lab-made hypothesis, accusing them of deliberate obfuscation of fact and “colluding” with the Chinese Communist Party.

Though scientists immediately condemned the study as disreputable and dangerous, it rapidly commanded a storm of social media attention, garnering more than 14,000 likes on Twitter and more than 12,000 retweets and quote-tweets within days of its posting. Shared on Facebook, Twitter and Reddit, it reached millions of users, and was covered in at least a dozen articles written in several languages.

The paper’s findings, however, have no basis in science.

“It’s ridiculous and unfounded,” said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at Columbia University who criticized the study on Twitter the day it was released. “It’s masquerading as scientific evidence, but really it’s just a dumpster fire.”

The publication is the second in a series from a team led by Li-Meng Yan, a Chinese scientist who released an initial paper on Sept. 14, also not peer-reviewed, asserting that the coronavirus was synthetic. Dr. Yan’s background is a little murky. She left her position as a postdoctoral research fellow at Hong Kong University for undisclosed reasons some time ago, according to a July statement from the institution, and fled to the United States. Both papers list Dr. Yan and her co-authors as affiliated with the Rule of Law Society, a nonprofit whose founders include Steve Bannon, a former White House chief strategist, who has since been charged in an unrelated case of fraud.

“That alone should give people pause,” Dr. Rasmussen said of the team’s connection to Mr. Bannon’s nonprofit.

Dr. Yan and her colleagues did not respond to a request for comment.

Their original paper — known as “the Yan report” — was also seized upon by thousands online and reported on in The New York Post, even though experts rapidly debunked its findings. Researchers called it unscientific and said it ignored the wealth of data pointing to the virus’s natural origins.

Close relatives of the new coronavirus exist in bats. The virus may have moved directly into people from bats, or first jumped into another animal, such as a pangolin, before transitioning into humans. Both scenarios have played out before with other pathogens.

“We have a very good picture of how a virus of this kind could circulate and spill over into human beings,” said Brandon Ogbunu, a disease ecologist at Yale University.

It may take quite some time to pinpoint exactly which animals harbored the virus along this chain of transmission, if scientists ever do at all — inevitably leaving some parts of the virus’s origin story ambiguous. Like many other conspiracy theories, the lab-made hypothesis “exploits the open questions in an ongoing investigation,” Dr. Ogbunu said.

But there is no evidence so far to support a synthetic source for the virus.

Dr. Yan’s Twitter account was suspended in September 2020 for pushing coronavirus disinformation. She shared the “second Yan report” from a second Twitter account, which has gained more than 34,000 followers.

Together, the papers written by Dr. Yan and her colleagues lay out what they identified as abnormalities in the genome sequence of the coronavirus. They suggested that those unusual features indicated that the virus’s genome had been purposefully spliced together and modified, using the genetic material from other viruses — a sort of Frankenstein’s monster pathogen, Dr. Yan told Fox News in September. The cousins of the coronavirus that had been identified in bats, they said, were also fake, human-made constructions, thus supposedly quashing the natural origin hypothesis.

The authors also contended that the coronavirus’s genome had been manipulated by scientists to enhance the virus’s ability to infect human cells and cause disease.

But outside experts have found no validity in either Yan report. The first was “full of contradictory statements and unsound interpretations” of genetic data from viruses, said Kishana Taylor, a virologist at Carnegie Mellon University.

And the second Yan report “was even more unhinged than the first,” said Gigi Kwik Gronvall, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and an author of a response debunking the original Yan report.

The supposedly strange features found in the genomes of the coronavirus and its natural relatives aren’t actually red flags at all, Dr. Ogbunu said. Viruses frequently move between animal hosts, changing their genetic material along the way — sometimes even swapping hunks of their genomes with other viruses. And many of the purported abnormalities in the coronavirus are found in other virus genomes.

The notion that the coronavirus was “designed” to be dangerous is also “just nonsense,” Dr. Ogbunu said. Scientists don’t know enough about viruses to predict which mutations would increase their lethality, let alone engineer these changes into new pathogens in the lab.

Building the coronavirus from such a mishmash of genetic templates, as described by Dr. Yan and her colleagues, would also raise herculean logistical hurdles for even the most dogged scientists. Part of this process would require researchers to laboriously tinker with thousands of individual letters in the alphabet soup that is a virus’s genome — an absurdly inefficient scientific strategy, Dr. Rasmussen said.

“Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,” Dr. Rasmussen said. “And this is not that.”

Site Index

Site Information Navigation

Source: Read Full Article