Since Major League Baseball’s players shut down the 1994 season with a work stoppage, only 13 teams have won a World Series. The Marlins have done it twice, with radically different teams, in 1997 and 2003. They’ve not been a factor in the National League East since the last of those wins, and never finished above .500 in the years between those two titles, either. This is the team’s 27th season in the Major Leagues, and it will almost certainly be the 21st in which the team finishes with more losses than wins; they are 19 games under .500 just 39 games into the season. There are few ways for a Marlins team to be bad in a way that the Marlins have not been bad before, but to watch this year’s team play is to know that they have earned their record.

And yet this organization has more World Series wins over the last quarter-century than any team besides the Yankees, Red Sox, and Giants; the Marlins have the same number of World Series wins during that period as the St. Louis Cardinals and at least one more than every other team in the sport. But where the Marlins’ apparent peers are associated with some combination of Tradition, Culture, and Opaque But Undeniable Supernatural Elements, the Marlins are widely and correctly understood to be about some very different things.

One of those fundamentally Marlins attributes is a dedication to open, shameless political graft. Another is a wildly cynical and multiply toxic institutional culture that has somehow survived multiple changes of ownership. Founding owner Wayne Huizenga bought the team with the money he made from his stake in Blockbuster Video—somehow the lurid teal jerseys the team wore were not the most 1990s thing about them—and won a World Series in 1997 with stars that money bought. He then dumped their expensive contracts as a matter of pure pissy principle and sold the team the next year.

Jeffrey Loria, in his second year of owning the team he acquired after having willfully run Montreal’s franchise into ruin, won a World Series in 2003 with mostly homegrown talent. He sold those players off too, but unlike Huizenga, Loria stuck around to do it again. Over those years he wrung billions in subsidies out of city and county taxpayers and grew but mostly shrunk the team’s payroll as a way to signal that he was committed to various things—to winning, or to competing, or to some sort of rebuilding plan. He never was, to any of those plans or to anything beyond his own grouchy aggrandizement and the pursuit of a big new stadium.

Since winning that World Series in 2003, the Marlins have never finished fewer than six games out of first place in their division. They only once even made it to 80 wins over Loria’s last eight years of ownership, despite developing not just superstars like Giancarlo Stanton and Jose Fernandez and Christian Yelich over that stretch, but other quality contributors who either matured enough that the team could trade them for parts (Marcell Ozuna, J.T. Realmuto, Hanley Ramirez) or flourished more or less as soon as they got out of Miami (they drafted Brad Hand and acquired Andrew Miller and got strikingly little out of either).

Advertisement

The 25 years of the Marlins’ existence has been a demonstration of a team that doesn’t know what it …

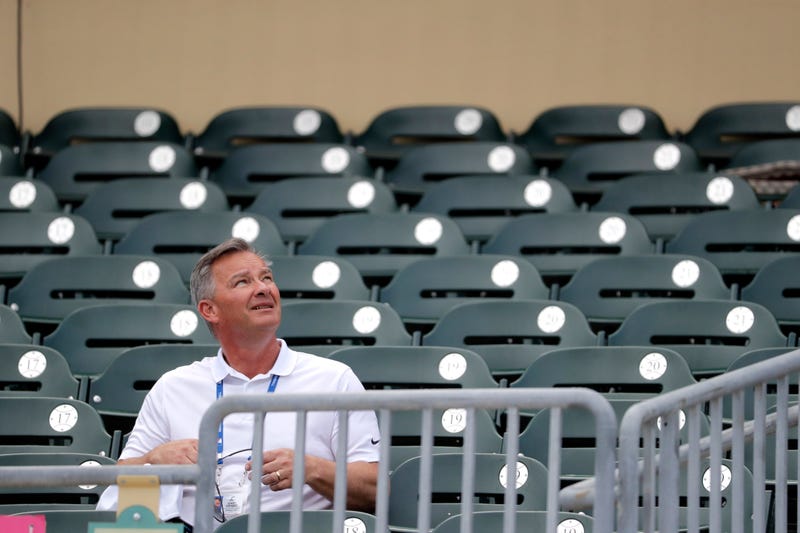

There were reasons to be wary when Loria finally sold the team to a group headed by financier Bruce Sherman and Ford Motor Company spokesmodel Derek Jeter in September of 2017. Most of those had to do with the fact that the new owners’ heavily debt-financed purchase immediately put the team underwater financially. On the other hand, neither Sherman nor Jeter was Jeffrey Loria. Totally different guys! It seems like a small thing, but then consider the alternative.

By this point in the new management’s tenure, though, it is clear that the Marlins are not better off under new management. They’re not even very different. The Jeter Administration, after a year and change, has been defined mostly by the classically Marlins roster immolation that began its tenure; the core of a promising but underachieving team was mostly traded away in the 2017 offseason, with Realmuto as last out the door after 2018. That paroxysm of furious self-destruction and clammy, dubiously self-actualized reinvention is just one of those things the Marlins do, and is as Floridian as humidity and citrus and retired cops from Long Island with too many bumper stickers on their cars. The new part was the broader institutional pose, which was expressed by Jeter through some odd-smelling Success Guy rhetoric about Creating A Winning Culture and Demanding Accountability. Jeter talked about the work that needed to be done in fixing a broken organization in the familiar Jeterish circularities, and brought in longtime Yankees player development hand Gary Denbo to do that work. “We’re putting into place accountability for how you go about your job here,” Denbo told Jerry Crasnick in an exceptionally credulous ESPN feature on Jeter The Executive from 2018. “We’re trying to raise the expectations and have higher standards in the organization.” This could mean any number of things, but it signaled that the people in charge were different than the dour cheapskates and overt scammers that preceded them. They were committed. To something.

Advertisement

Last week, The Athletic’s Ken Rosenthal wrote about what the Marlins’ attempt to Create A Winning Culture looks like on the ground, in a long story centering on Denbo, whose official title with the team is Director of Player Development and Scouting. “A consistent portrait of Denbo as an unyielding authoritarian emerged in interviews The Athletic conducted with more than 20 former Marlins employees and a dozen others in baseball over the past 11 months,” Rosenthal writes. “Those former employees say Denbo engaged in verbal abuse, fat shaming, and blatant favoritism toward certain Marlins personnel.”

Professional that he is, though, Rosenthal begins with the bat dogs. The Marlins’ Low-A affiliate in Greensboro, N.C., had used dogs to pick up bats and run balls to the umpires since 2006; fans loved the dogs, and the bucket that a long-serving Labrador Retriever used to bring balls out before the game is currently in Cooperstown. Denbo didn’t like this, and really didn’t like that the dogs’ kennels were in the team’s clubhouse. He made the accountability-driven executive decision to scream at a clubhouse attendant about it and Greensboro’s G.M. and president refused to work with Denbo and the team’s 16-year relationship with the Marlins was over. “There must be only one guy in all of minor-league baseball who doesn’t like dogs,” the G.M. told Rosenthal.

Advertisement

The other Tales Of Denbo in the story are not quite as clearcut—for sheer heel-turn economy, it’s tough to top howling at a clubbie about Labradors—but the portrayal that emerges is not flattering. Denbo overhauled the Yankees farm system between 2014 and 2017 to great effect and is revered as a hitting coach; he is apparently also widely regarded as a bullying and relentlessly aggro prick. He was hired by Jeter to make the Marlins more like the Yankees, though, and this is how he and Jeter are going about doing that.

For all the talk about culture and accountability, the sense that the Marlins are ruled by opaque executive whims remains unchanged. When Jeter fired the president of business operations that he’d hired 14 months earlier, he cited expectations unmet, with special attention to the fact that people in Miami remain uninterested in paying to watch the Marlins lose 5-1 to the Nationals on a Tuesday. Attendance has been a special fixation of Jeter’s since his first days on the job, and is a problem he appears to believe he can solve by talking about how committed he is to solving it. That all this talk has come alongside owners unabashedly stripping the copper wiring out of the walls in every sense but the literal one speaks to a different sort of commitment, and a combination of brazen cynicism and smug laziness that will be familiar to many with a job and a boss in 2019.

Given the checked-out tightwads and grifty buttheads that have owned the team in the past, the Marlins were undoubtedly due for a cultural shake-up. Rosenthal’s story can be docked a point for a Disgruntled Employee here and there, but it does a good job of illustrating the actual commitments of the people in charge. Denbo’s signature executive approach could be termed Insult To Inspire; he seems to believe that the team had failed in the past because no one in leadership had dared to call the team’s scouts fat-ass idiots in an all-hands meeting.

Advertisement

The irony of all this is that a real commitment and a new culture are exactly what the Marlins need. Acts are more meaningful than faith in this particular area, but also notably more expensive; taking seriously the work of building a team that works and plays and spends like a proper Major League organization is a commitment that no Marlins owner has ever really made. Jeter doubtless believes what he professes, but stripping the team of talent while talking about how committed he is to Commitment suggests some limits to the sense of accountability he’s working to instill. All these big ideas are nothing without the courage to spend money on baseball-playing humans to make them real, but that last bit is clearly secondary here. The point is to let the powerful people up top, the ones that exist outside this Culture Of Accountability, tout their values and feel busy and smart. If the team is losing or demoralized or adrift, the answer will always be sloshing some more accountability downhill.

Denbo might just be one entitled jerk, albeit one who happens to be one of the CEO’s oldest buddies and holds a powerful position, but such a person only winds up using that job to insult and demean everyone under him if the institution that hired him has failed. Not just failed at protecting its employees from a bully, but failed to understand that accountability is only really accountability when it applies to everyone.

Source: Read Full Article