A reporter who trades in scoops should have only one responsibility: to get it right. Regardless of the size of the scoop, it can’t be bogus. Yes, sometimes sources mislead reporters to serve their own purposes. But there’s only a limited pool of sources for this kind of transactional stuff, anyway: The people in the know are front-office staff, agents, or players. Even if they each have their own agendas, that comes with the territory and doesn’t necessarily disqualify them as useful sources. But it is the job of a scoop trader to figure out whose interests are actually coloring the facts they pass along. If a reporter doesn’t have the ability to parse that and keeps getting burned, their credibility gets singed, too.

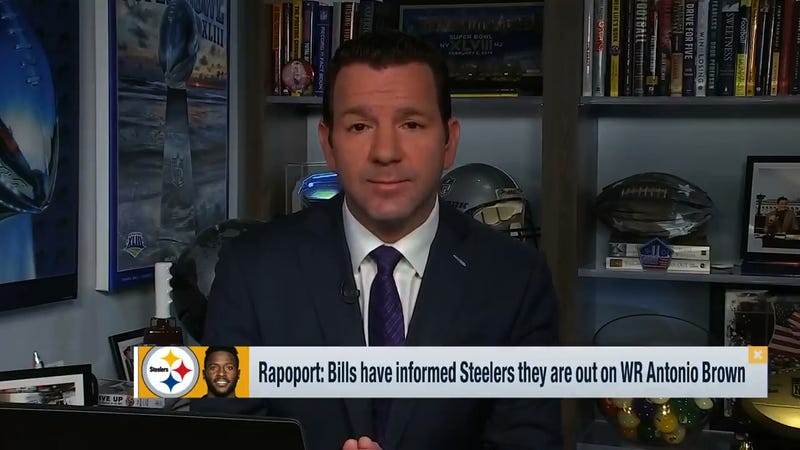

On March 8, NFL.com and NFL Network scoopster Ian Rapoport reported that the Steelers were “closing in on a deal” to trade disgruntled receiver Antonio Brown to the Buffalo Bills. He added a little flourish at the end of the news, as it had been expected that Brown would be shipped somewhere in the offseason. The deal never actually happened, though, and throughout the night Rapoport added details to soften the very expectations he had raised:

Advertisement

Brown was still on the Steelers the next morning. The WR ended up going to the Oakland Raiders in a deal reported on March 10. Bills GM Brandon Beane admitted that the team had engaged in trade discussions, but “ultimately it didn’t make sense for either side.”

When I called Rapoport this week to learn more about how his reporting had unfolded, he insisted his source hadn’t given him bunk information. To prove there was truth to his report, he referred to Mike Mayock’s quotes when the Raiders introduced Brown on March 13. The Oakland GM—who worked as an analyst for NFL Network before the Raiders hired him in December—said that to his knowledge, the Bills’ deal for Brown had dissolved:

We weren’t even in on the process until Friday. I’m not going to get into specifics, but the bottom line is that I think Pittsburgh wanted a certain pick, we weren’t going to be able to get there. When that deal fell through with Buffalo, we got involved and I’ll tell you a couple things: I thought [Steelers GM] Kevin Colbert from Pittsburgh did a great job in getting this thing close. I think [Brown’s agent] Drew Rosenhaus was amazing because there were some times where I wasn’t sure if we were going to get there or not. Any time you have a high-profile negotiation like this, there are points to be made by both sides. You have to get through some things. Drew did a great job keeping this thing alive.

Advertisement

There’s enough on-the-record information here to reasonably determine that Rapoport wasn’t wrong at the time he said the Bills were close to a deal for Brown. He would’ve had a better case if he hadn’t declared at the end of the tweet, “There it is.” I asked Rapoport why he had written that.

“Basically my meaning on that was, ‘This is the team,’” Rapoport said. “We were all searching for which team it would be. You know, I would say maybe it’s not the greatest phrase. It’s sort of a cliché anyway, so not something that I would probably use again, even though I did use it at two in the morning two nights later.

“But, I mean, I did not say the trade was done. Now, I mean, if I could do it again I would have been more specific in saying, like, ‘The trade parameters are agreed to. This is close. But there are other issues to work out.’ But, you know, those are the things that I ended up talking about on TV a lot, but on Twitter, it got amplified and that’s what a lot of people read.”

Advertisement

Reasonable minds can disagree on the effectiveness of a justification—“it got amplified”—that is, functionally, a lot of people saw my tweet. And it feels fair to say that this was not the first time Rapoport’s choice of wording on Twitter bit him in the ass. In 2013, he reported this bizarrely complex item about quarterback Ben Roethlisberger:

“Expect.” “To ask.” “To explore.” If he needed two infinitive verbs to couch his reporting and then wrap the whole thing in conjecture, perhaps it was worth holding the news to get more out of the source, because in that form, it meant nothing. (The Steelers did not trade Roethlisberger that season.)

Advertisement

Last season, when he reported a quarter-long suspension for Patriots receiver Josh Gordon that never happened? Rapoport used to be a beat writer for the Boston Herald, so he should’ve had some reliable connections within that team.

Gordon ended up playing from the start of that Monday night game against the Bills, and Rapoport didn’t provide a useful explanation on why he was wrong. Here’s a transcription of what he said on his podcast, via Patriots Wire:

“It was on Monday afternoon I got a tip that Josh Gordon was informed that he was going to be sitting out a quarter of the game against the Bills because of discipline. I was told he had a lateness, and so I checked on it. I had three sources confirm that Gordon was informed that he was going to miss a quarter. Other reporters, including Mike Giardi, reported that it wasn’t one lateness; it was actually two. He was late to the team flight and he was late to a meeting, and I checked all the boxes and I went with my report. And then first play of the game, there goes Josh Gordon on the field. And so everyone wants to know what happened.

“And I will say the honest truth is, I do not know. Sometimes the reporting of things and getting it out there, especially before the game, does change what actually happens, but I may never know. I have since gotten calls from people who confirmed it to me calling me and asking me what changed, and I literally have no idea.”

Advertisement

How about when Rapoport divulged during the 2017–18 playoffs that the Titans would extend head coach Mike Mularkey, only for them to fire him a day later?

This was similar to the Brown trade, in that Rapoport dug his own hole when he didn’t need to. “He’s staying” made it seem like Mularkey was … well, staying. It was a definitive claim, which was odd to put in a tweet that broke news about an offer. This was how Rapoport reacted when Mularkey was fired:

Advertisement

Rapoport’s original report came the day after the Patriots beat the Titans in the playoffs. He added, after Tennessee canned Mularkey, that the team was uncertain about keeping the coach in the first place. Why was Rapoport so sure in the original tweet if he knew that was the case? This instance provoked the ire of former NFL Network colleague Rand Getlin:

Advertisement

Here’s another one: On Sept. 3, 2017, before the start of the regular season, Skins safety Su’a Cravens abruptly announced his retirement. Two weeks later, Rapoport dug up a nugget and proudly presented it to the class: Cravens would be returning to the team. This was how he worded the news:

According to several sources, Cravens is expected to report back to the team early this week, likely on Tuesday. The situation is complex and fluid, and simply reporting may not be the end of the story.

Advertisement

What the fresh hell does that second sentence mean? The next day, the Skins placed Cravens on injured reserve. He didn’t play at all in 2017 and was traded to the Broncos the following offseason. This is not an argument that Rapoport should be on the hook for predicting the whims of a front office as incompetent and capricious as the Skins; it’s that he had only a half-baked piece of news and tried to present it as more than that.

Rapoport is far from the only national football reporter who screws up. ESPN’s Adam Schefter, who is seemingly always awake and never shameable, pushed the idea that there were bigger fish than Patriots owner Robert Kraft caught up in the Florida prostitution bust, bigger fish that apparently do not exist. Dianna Russini, another ESPNer, mangled the passive voice to suggest that Bill Belichick and Tom Brady would retire at the conclusion of Super Bowl 52, then walked it back after an hour and claimed her tweet had never been a report in the first place. Rapoport’s NFL Network colleague Mike Garafolo botched the breakup of Landon Collins and the New York Giants just a couple of weeks ago.

There are two types of scoops: the speculative, and the dry passing-along of something that’s happened. Rapoport knows the former is a minefield of sources with agendas.

Advertisement

“There are facts, like, this person has been cut. That’s a fact. This person tore their ACL, that’s a fact. But almost everything else, there’s a reason you’re finding it out,” he said. “A lot of it is because you just happen to know and then someone says, ‘Yeah that’s true. You’re right.’ There’s no perspective there, but a lot of it is like, ‘Hey, I’m gonna give you this,” and you can tell where the person’s coming from.

“So for contract numbers, let’s say it’s an agent. A lot of times, they give you the max number. If it’s a team, they give you the base number. I mean, there’s there’s a lot of different perspectives as far as why I get news or people like me. Right? So, there’s always a reason. So I think the main thing for me and for all of us to do my job is to figure out why you’re getting the information. How did it come to you? There’s a lot of times when, in free agency, teams will say to you, ‘Hey this player’s going here and I know this because we’re out.’ And then you’re like, ‘Okay, is that true? Why am I getting this? For them to throw me a bone, or for them to get someone to flip?’”

A scoopster’s value, then, is just as much in being able to sift through disinformation as it is building the relationships with sources in the first place. That becomes more difficult when reporting something falsifiable that hasn’t occurred yet.

Advertisement

It’s common for reporters to use the future tense—you can’t be first on a story until you wait until after it’s happened to report it—and Rapoport usually does it too, but he also has a self-admitted tendency to add a personal reaction that actually changes the expectations of what he’s reporting. “The main thing is, the language we use is so important,” he told me. “And when something big is happening, obviously it’s exciting, and the inclination is to be like—just to add to it.” It’s fine for a reporter to react to the wild news they’re breaking. They’d better be sure it’s absolutely happening, though.

Source: Read Full Article