More from:

Mike Vaccaro

Albert Pujols, Chris Paul latest to prove old guys rule

Why this Subway Series is so important for Yankees, Mets

Simulating an all-time modern Subway Series between Yankees, Mets

This Islanders defeat will sting for a while

Islanders hoping this do-or-die chance ends as happily as their first

The Suns had waited just over 52 years to exact their revenge when the ball was tipped just past 9 o’clock Tuesday night at Phoenix Suns Arena, signaling the start of the 2021 NBA Finals. In so many ways this is a rematch the Suns have coveted since March 19, 1969, when they had their first-ever crucial match.

That, too, involved the Milwaukee Bucks as a foil.

There were no basketballs in play that day, just a four-way conference call connecting New York City, Phoenix, Beverly Hills and Milwaukee. At stake was the most important sweepstakes in the sport’s history.

Both the Suns and Bucks had been awful in their maiden NBA voyages of 1968-69. The Bucks, playing in the East, were 27-55, five games clear of the next-worst team in the conference (Detroit). The Suns were even worse, at 16-66, some 14 games worse than Seattle. There was no questions of tanking. These were expansion teams who’d earned their record on merit (or lack thereof).

Of course, the prize in question would’ve been worth a full-blown tank.

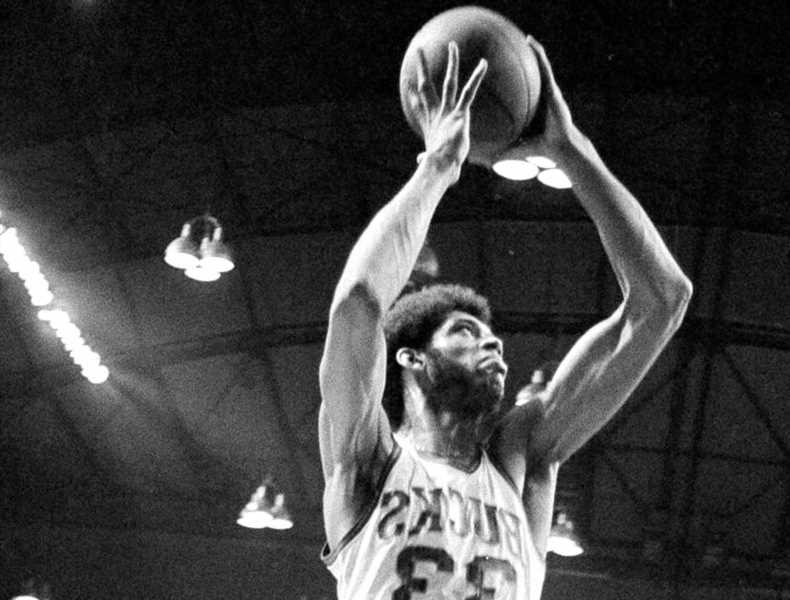

That was Lew Alcindor, UCLA All-American, who in a few days would lead the Bruins to their third straight NCAA championship in his three-year stay in Westwood. There had never been a bigger prize in an NBA draft, ever; even when Wilt Chamberlain was coming out of Kansas (by way of the Globetrotters) he had been a territorial pick of the old Philadelphia Warriors.

This time it was simple:

Winner got the right to Alcindor, and all the tantalizing promise that went along with that.

Winner didn’t.

NBA commissioner Walter Kennedy would flip a coin inside the NBA’s offices in Manhattan. He carefully explained the kind of coin they would be using — a 1964 JFK half-dollar. Joining the call was Suns GM Jerry Colangelo, Suns president Richard Bloch from Beverly Hills and a contingent of Bucks brass led by GM John Erickson and chairman Wes Pavalon.

The Suns had already won the first mini-battle of the day, earning the right to call the coin while it was in the air. They’d opened that to a vote of their burgeoning fan base in the Valley of the Sun and by acclimation the people had chosen “heads.”

Kennedy tossed the coin in the air.

“It felt,” Colangelo said years later, “like it took two weeks for it to come down.”

It was only a second or two.

“Tails,” Kennedy said.

And in an instant, the fates of two franchises were altered for the foreseeable and long-term future. The Bucks selected Alcindor — who would soon adopt the name Kareem Abdul-Jabbar — and then held off the Nets, who owned Kareem’s ABA rights (the story of how the Nets sabotaged themselves on that one is epic, and worthy of another column on another day).

Alcindor gave the Bucks instant credibility: in his rookie year they won 56 games and a playoff series before being trounced in five by the Knicks, but by 1971 they’d added Oscar Robertson, won 66 games and went 12-2 in the playoffs en route to the city’s first major league title since the 1957 Braves. In 1974, they returned to the Finals and dropped a seven-game classic to the Celtics.

The Suns?

“I’m disappointed, of course,” Colangelo, then the Suns’ 28-year-old boy wonder GM, said a few minutes after the reality of “tails” sank in. “It makes our job that much harder now in regard to the draft. We have big decisions to make now. We have a number of players under consideration for our No. 1 pick.”

Yeah. About that. It turned out the 1969 draft was absurdly top-heavy. The only other notable players to go in it were JoJo White to the Celtics at 9 and Norm Van Lier to the Bulls at 34. The Suns went with 6-foot-10 Neal Walk, who’d had a fine college career at Florida (1,600 career points) and was a serviceable NBA center for eight seasons (including his last three as a Knick), averaging 12.6 points and 7.7 rebounds.

But …

Well, through no fault of his own, Walk’s claim to fame is as the NBA’s ultimate consolation prize, its ultimate parting gift. The Suns did make the Finals in 1976 and again in 1993, but have never gotten where the Bucks got on the strength of their first-ever critical meeting, some 52 years ago. It was time for a rematch.

Share this article:

Source: Read Full Article