I WAS KATO. So was everybody else. We all wanted to be Kato, and fought each other for the right to fight like him. We had learned to put up our dukes, growing up on rough-and-tough Long Island. But Kato put up his feet. He challenged our idea of what was forbidden and expanded our idea of what was allowed. He kicked. He used his hands like claws as much as he used them as fists. He made sounds like an alley cat and had the body of a scorpion, small and sleek, all tensile strength. He was the only reason to watch “The Green Hornet,” a superhero show whose titular character wore what our fathers wore to the commuter train on rainy days, a hat and an overcoat. Kato was the sidekick, but he was also the superhero. No, he couldn’t leap tall buildings in a single bound. But he could fly, delivering his kicks from out of thin air. He could break boards bare-handed. He had superpowers to which suburban boys could aspire. We had never seen anyone like him, and yet he was one of us.

Us: Back then it was an even more limiting word than it is now. In the Long Island of the 1960s, almost everyone I knew was a first-generation suburbanite reared by men and women who were second-generation immigrants. We were taught to believe in the ethos of the melting pot, but also that our parents had “escaped” from tough neighborhoods in New York for a “better way of life” on the Island. We were so convinced of our status as scrappy underdogs that most of us never thought to question the racial exclusivity of neighborhoods that were simultaneously “ethnic” — Irish, Italian, German, Jewish — and all white. The only place we occasionally challenged the color line was in our choice of heroes, where we were free to argue that Willie Mays was a better ballplayer than Mickey Mantle.

Kato was a hero. But we couldn’t help but be aware that he was something no hero of ours had ever been. Behind the leather mask and the chauffeur’s livery, his name was Bruce Lee, and he was Chinese. To want to be him was to face the uncomfortable realization that he wasn’t allowed to be us. And for me, it was an introduction to my own future, which many decades later has turned out to be, in the most personal way possible, a Chinese one.

WHEN I WAS growing up, it was the most ingrained and least examined prejudice.

My mother and father openly reviled Asians, and so did the mothers and fathers of many of my friends. By the time “The Green Hornet” debuted in September 1966, barely 20 years had passed since the fireballs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended World War II. Even parents who kept their prejudices against black people to themselves thought nothing of pulling at the corners of their eyes and barking what they thought to be pidgin Japanese at boozy backyard parties, the power of racism erasing the distinction between the aggressors of the Eastern theater and their primary victims. It was a terrible irony of the postwar years: Japan and China, two countries enmeshed in centuries of conflict, came to be seen as nearly identical by virtue of their both being “Oriental” in the minds of so many Americans. In the three decades since 1941, the United States had fought wars against Japan, North Korea and Vietnam. But what I heard in my home was my father telling my mother to pick up fried rice from “the C—ks” and voicing his distrust of the “Chinaman” who washed his shirts.

Television and movies were no more enlightened. The kids who watched Kato on “The Green Hornet” also watched Oddjob in “Goldfinger” and Hop Sing on “Bonanza,” the former a silent Asian butler with a lethal bowler hat and the latter a helpless and excitable cook humored and protected by the valiant Cartwright clan. The message, in either case, was the prevailing one: In order to gain entry to American popular entertainment, Asian men had to be sinister or emasculated. They had to be servants, as peripheral to the eye of the camera as they were to the story. They couldn’t be leading men, and their bodies weren’t shown unless they were sumo wrestlers. And they could never, ever win a fight.

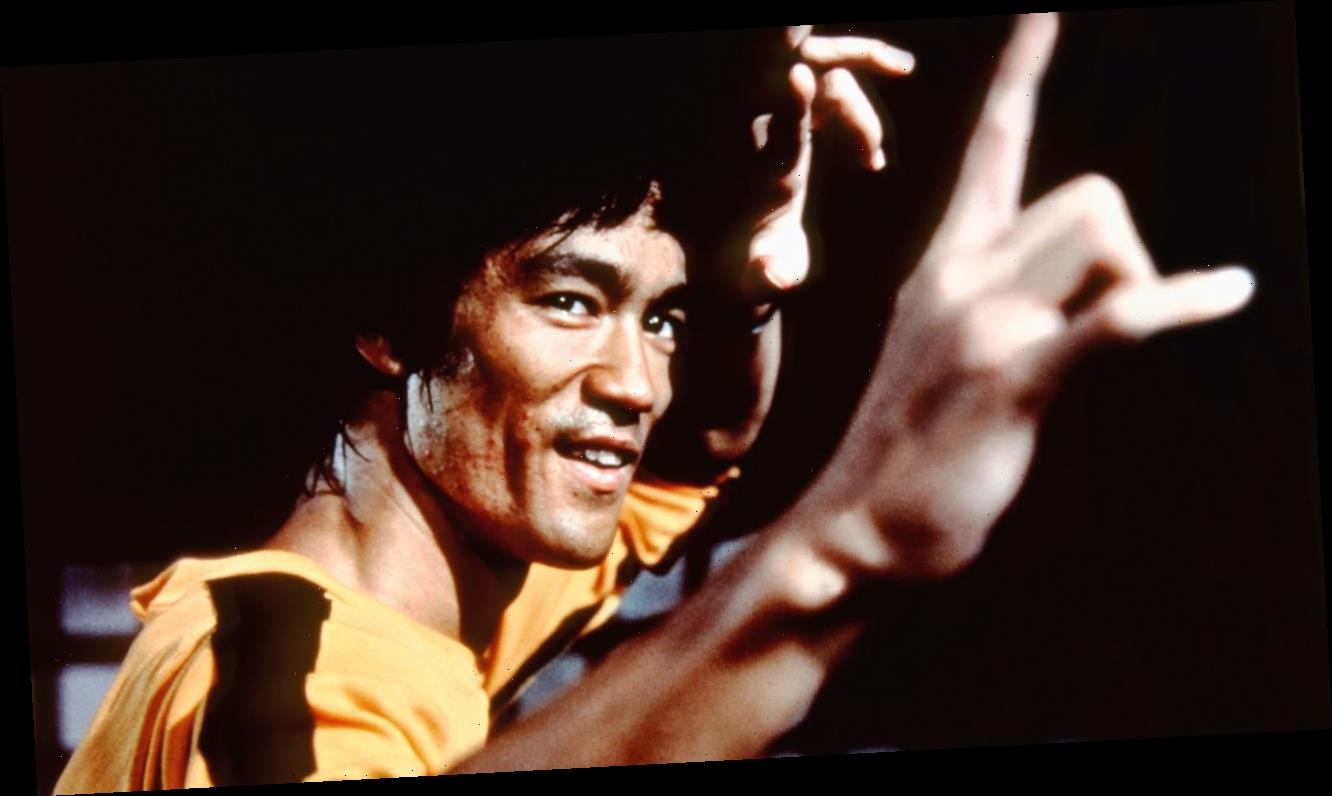

Bruce Lee won fights. But his victories were more than the result of his skills in kung fu, the discipline he helped introduce to the United States. In “Be Water,” the new 30 for 30 documentary debuting on ESPN on June 7, Bruce Lee steps out of the past as a man who had to fight for everything, including his right to be a fighter. From his scene-stealing entrance in 1966 as Kato to his eventual apotheosis seven years later in “Enter the Dragon,” he fought for the right to be a hero and he fought for the right to display his body and he fought for the right to be a leading man. He fought for the attention of the camera, as if daring his non-Asian audience not only to look but also to look away. It didn’t. I didn’t, and neither did many of my contemporaries. We couldn’t take our eyes off him and recognized him for what he was then and what he remains now:

An American original.

THE SECOND HALF of the 20th century, sometimes known as the American century, was prolific in the production of people the likes of which no one had ever seen. There was Elvis Presley. There was Muhammad Ali. There was Little Richard. There were Nina Simone and Janis Joplin, Malcolm X and Mister Rogers. There were — well, there were many more men and women who comprised the core and corps of American originals, an oxymoronic legion of the unique. We call them icons now. Back then, they were emblems of rebellion and proof of America’s promise, fulfillment of a magpie version of the American dream, improbable here, impossible anywhere else. The originals were melting pots unto themselves, immigrants of heart and soul who very often changed their names in the cause of their assimilation and also in the cause of their refusal to be assimilated. Often rejected, they brokered the terms of their acceptance by ingenuity and sheer will. They appropriated from other cultures with abandon and formed an unlikely aristocracy of the influential. They were fluid at a time when fluidity was suspect. In most cases, they wanted to be somewhere or someone else. In all cases, they turned out to be entirely themselves and created a whole new kind of American identity — one that was, yes, like water.

Bruce Lee was one of them, an original in a line of originals. He was, like all the rest, cool in the only way that term can be defined: You knew it when you saw it, and when you saw it you wanted to be it, or at least tape a poster of it to your wall. He was cool as Elvis and Ali were cool, to the extent that Elvis eventually stopped shaking his hips onstage and started doing kung fu routines instead, and Ali came under the tutelage of a martial arts master. He was cool because he was committed to being cool no matter the cost, and the possibility that his days were numbered became part of his mystique. He was never anything but cool, and yet, while a member of the only club that counted, he was also its first and only Asian. And his singularity raises a question: Was he cool because of his heritage or because he transcended it? Did he belong to the American audience that claimed him or to the Asian audience he took such pains to represent? It is not easy to become a universal hero while straining to stay a specific one. It is not easy to tell a simultaneous story of escape and arrival, but that’s precisely the story Bruce Lee was determined to tell, fated to tell, from beginning to end.

HE WAS BORN in San Francisco. He grew up in Hong Kong, where he became a child star. In the late ’50s, he moved back to the United States, where his dream of opening a chain of kung fu schools took him to Hollywood. He returned to Hong Kong after he proposed the story of a wise martial artist to a television network and the network instead developed a similar show, “Kung Fu,” with a Caucasian actor, David Carradine, in the leading role. He began making martial arts movies in Hong Kong, and in his second, “Fist of Fury,” about a Chinese kung fu student avenging the death of his master against the Japanese colonial power, he made full use of his magpie’s treasure. He sneered like Elvis. He dominated the camera like Marilyn Monroe. He walked as theatrically as Charlie Chaplin and killed as remorselessly as Clint Eastwood. When facing a fighter of greater strength, he got up on his toes like Ali, floating like a butterfly and stinging like a bee, and his dubbed voice sounded unmistakably like John Wayne’s. He never relaxed and was never unaware that we were watching. Just as he remained Asian when he came to America, he remained American when he returned to Asia. When I first saw him as Kato, he was sporting a chauffeur’s cap and a uniform jacket buttoned primly to the neck. When I saw him again in “Fist of Fury,” he emerged shirtless and relentlessly jacked, as beautiful and doomed as any rock ‘n’ roll star. He was dead in a year.

Lee tells us exactly who he is in “Be Water” when he discusses his heterodox fighting techniques: “I personally do not believe in the word ‘style.’ Because of style, people are separate. They are not united together, because styles become law.” He is talking about fighting styles and the unorthodoxy of his technique. But of course he is also talking about everything else. Today, he is rightly celebrated as an Asian American pioneer, somebody who changed the rules of the game. And yet there was a time when by being cool he represented, well, me, and untold numbers of kids like me, white, yellow, black and brown. We are desperate for that kind of hero today, but it’s hard to imagine his return, because people are separate and styles have become law. We have come to distrust the weapons Bruce Lee kept in his arsenal — the strategies of appropriation and assimilation.

Was Bruce Lee authentic? He was clearly athletic, the way Baryshnikov was athletic. Was he an athlete? Could he fight? Was he … a fighter? It is hard to find footage of him in a fight that is not choreographed, and in some ways he is about as authentic as one of Ali’s role models, the professional wrestler Gorgeous George. He pays the price for this presumed fraudulence in Quentin Tarantino’s “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood,” where, in a sign of our time but not of his, he is portrayed as a ludicrous braggart who boasts he could beat Ali in a fight and then loses a fight to a stuntman who figures as the film’s white cowboy hero — where the first Asian I ever saw win a fight on American television gets unceremoniously tossed into a parked car by Brad Pitt.

Could Bruce Lee have beaten Muhammad Ali in a real fight? Could he have beaten Brad Pitt? It doesn’t matter to anyone but Tarantino. He arrived on the American scene not simply when Asian men couldn’t be considered leading men but when they were barely considered men at all — when they were, in the words of his daughter Shannon, “thoroughly dehumanized.” When he came to this country, he was 18, and men like him never won; when he died 14 years later, he never lost.

That’s an authentic accomplishment by any standard, but here’s the standard that counts for me: Back when I wanted to be Kato, I encountered Asian Americans only at the Chinese laundry and the restaurant that was rumored to serve cats. Now I have a daughter born in China. When she was a little girl, she demolished the anti-Asian animus my parents cultivated over a lifetime, and just by refusing to be anyone but herself she became, to them, a source of wonder. And my mother, in the last years of her life, became not the “Grandma” or “Nana” she was to her other grandchildren, but rather the proud “Po Po.”

My mother and father died when Nia was a little girl, but she still remembers their embrace. She is 17 now and faces complications rooted in her divided and doubled identity, fretting that she, as an Asian, is considered by many to be privileged and therefore “white,” and also that Americans are being primed to blame Chinese people for the pandemic. My wife and I tried to steer her into an awareness of her Chinese culture by the usual means favored by adoptive parents — lessons in Chinese dance and language — but she has found her own way through YouTube and TikTok videos. And so when I asked her to watch “Fist of Fury” the other day, she scoffed as if I’d asked her to watch “Gone With the Wind.” The movie wasn’t part of her past but rather of mine, and she didn’t need Bruce Lee.

But once upon a time on Long Island, I did — at least when it counted, which was when I couldn’t know it counted, which was when all I wanted was to be Bruce Lee no matter the implications. Can I say that my boyhood admiration of Bruce Lee led me to adopt my daughter? It’s hard to draw a straight line from one to the other. But it’s impossible to draw any line at all without him, because he was the first — and he was the first so that he wouldn’t be the last. By fighting for himself, he fought for his people, my daughter included. But he also fought for me, and he fought to win.

Source: Read Full Article