Self-isolation and contactless deliveries are nothing new: Britons adopted similar measures to help prevent the spread of plague in York during the 17th century, stone inscription reveals

- Plague struck the city of York in the year 1604, forcing measures in response

- Afflicted city-folk left the city to isolate in wooden lodges on a moor to the south

- A marker stone served as a ‘contactless’ drop-off point for food for the sick

- Coins as payment were left in a bowl-like indent full of cleaning water or vinegar

Self-isolation and sanitising are nothing new, as Britons adopted similar measures to help prevent the spread of plague in York during the 17th century.

A small stone on a moor about a mile south of York’s city walls tells the story of how the city dealt with an outbreak of the plague in the year 1604.

The epidemic — in what was then widely considered England’s second city — prompted strict measures to protect the wider public from those who fell ill.

The bubonic plague — also known as the ‘Black Death’ — struck across Europe and the Mediterranean repeatedly between the 14th and 17th centuries.

Scroll down for video

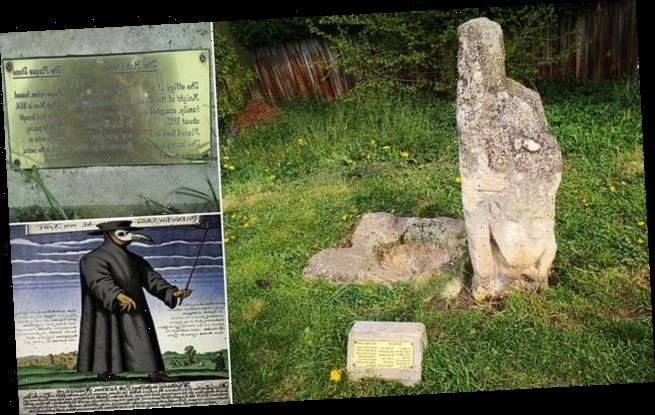

Self-isolation and sanitising are nothing new, as Britons adopted similar measures to help prevent the spread of plague in York during the 17th century. Pictured, York’s Hob Stone (left) and Plague Stone (right), on Hob’s moor. Food would be left for the ill by the plaque stone, whose bowl-like depression would have held water or vinegar to sanitise coins paid in return

A small stone on a moor about a mile south of York’s city walls tells the story of how the city dealt with an outbreak of the plague in the year 1604. Pictured, the plaque by the plague stone

Sufferers of the plague in York in 1604 had to leave the walled city and travel a safe distance away — as to protect the other inhabitants.

One such refuge for the sick was Hob Moor — a site near the city’s modern-day racecourse, where cows still graze but which is now surrounded by housing estates and allotments and cut-through by the North East railway line.

Those afflicted with the plague would have likely left the city through Micklegate Bar, which was one of the four principal gates to the city and the one traditionally used as an entry point by visiting monarchs.

Isolating city residents would have taken refuge in wooden lodges on the moor, a mile south of the gate, where they could not pass on the disease to the general population inside the walls.

The plague stone now rests next to the taller Hob Stone, which was carved in 1315 to depict a knight of the Roos family that gave the surrounding common to the poor.

Unfortunately hundreds of years of erosion have rendered the portrayal of the warrior scarcely recognisable.

During the 1604 outbreak, the plague stone would have served as marker where food was dropped off for the afflicted to eat.

Much like with the contactless deliveries of the present COVID-19 pandemic, the isolated would collect the provisions once the deliverer had safely retreated.

In the 17th century it was mistakenly thought that the bubonic plague was transmitted via money.

Accordingly, a depression on top of the stone would have once been filled with water or vinegar in which coins could be cleaned and left as payment for the food.

Those afflicted with the plague would have likely left the city through Micklegate Bar, which was one of the four principal gates to the city and the one traditionally used as an entry point by visiting monarchs. Pictured, Micklegate Bar in the present day

In the 17th century it was mistakenly thought that the bubonic plague was transmitted via money. Accordingly, a depression on top of the stone would have once been filled with water or vinegar in which coins could be cleaned and left as payment for the food

The bubonic plague — also known as the ‘Black Death’ — struck across Europe and the Mediterranean repeatedly between the 14th and 17th centuries. Pictured, an artist’s impression of a mid-17th century plague doctor

Today, York retains its historic walls, which surround virtually the whole of the old city.

Those living inside the old city boundary who are badly affected by COVID-19 will still likely have to travel beyond it for treatment.

This time, however, the district hospital at Clifton, to the north of the city centre, will be their likely destination.

Sufferers of the plague in York in 1604 had to leave the walled city and travel a safe distance away — as to protect the other inhabitants. One such refuge for the sick was Hob Moor. Those afflicted with the plague would have likely left the city through Micklegate Bar, which was one of the four principal gates to the city

WHAT CAUSED EUROPE’S BUBONIC PLAGUES?

The plague, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, was the cause of some of the world’s deadliest pandemics, including the Justinian Plague, the Black Death, and the major epidemics that swept through China in the late 1800s.

The disease continues to affect populations around the world today.

The Black Death of 1348 famously killed half of the people in London within 18 months, with bodies piled five-deep in mass graves.

When the Great Plague of 1665 hit, a fifth of people in London died, with victims shut in their homes and a red cross painted on the door with the words ‘Lord have mercy upon us’.

The pandemic spread from Europe through the 14th and 19th centuries – thought to come from fleas which fed on infected rats before biting humans and passing the bacteria to them.

But modern experts challenge the dominant view that rats caused the incurable disease.

Experts point out that rats were not that common in northern Europe, which was hit equally hard by plague as the rest of Europe, and that the plague spread faster than humans might have been exposed to their fleas.

Most people would have had their own fleas and lice, when the plague arrived in Europe in 1346, because they bathed much less often.

Source: Read Full Article