A bad time to be alive’: More than half of all Earth’s ocean life died off 444 million years ago because it ran out of oxygen, study shows

- Researchers studied samples of black shale from the Murzuq Basin in Libya

- They used this and existing data to build a model of ancient ocean oxygen levels

- It suggested severe oxygen loss likely struck ocean bottoms across the globe

- This three-million-year-long event killed around 85 per cent of marine species

More than half of all of Earth’s ocean life died off 444 million years ago because of falling oxygen levels, a study has found.

Experts believe that the ‘Late Ordovician’ mass extinction 450 million years ago was due to widespread ‘anoxia’, or oxygen depletion, over a three million year period.

The Late Ordovician event was the first of out planet’s ‘big five’ mass extinctions — although some experts believe humanity is presently causing a sixth.

The researchers hope that their findings will help scientists better monitor oxygen in the oceans occurring as a result of modern climate change.

Scroll down for video

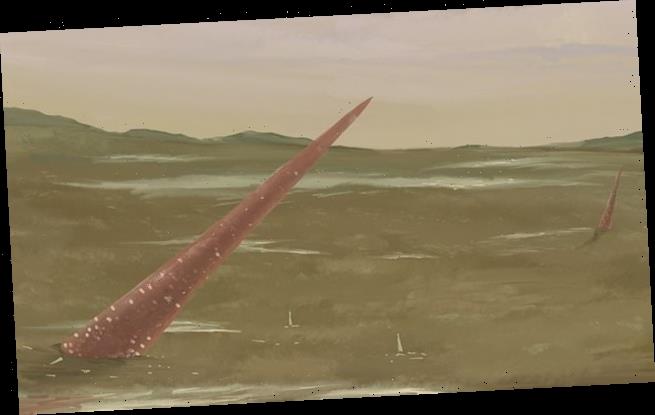

More than half of all of Earth’s ocean life died off 444 million years ago because of falling oxygen levels, a study has found. Pictured, an artist’s impression of the cone-like shells of dead Cameroceras shells sticking up out of the muddy foreshore after the extinction event

‘Our study has squeezed out a lot of the remaining uncertainty over the extent and intensity of the anoxic conditions during a mass die-off that occurred hundreds of millions of years ago,’ said geologist Richard Stockey of Stanford University.

‘But the findings are not limited to that one biological cataclysm.’

At the outset of the Late Ordovician event, the world was a very different place than it is today, with the vast majority of life to be found in the oceans, with plants having only just begun to appear on land.

Most of the modern-day continents were jammed together as a single super-continent, which researchers have dubbed Gondwana.

An initial pulse of extinctions began as a result of global cooling, which left Gondwana covered by glaciers around 444 million years ago.

Over the next three million years — a period dubbed the Hirnantian–Rhuddanian boundary — a second pulse of extinction wiped out around 85 per cent of marine species.

Previous studies gleaned valuable information about ancient oxygen levels by looking at changes in radioactive metals caused by different levels of the gas. Using this information and new data from samples of black shale from the Murzuq Basin in Libya, researchers created a new model to map out the oxygen levels in the prehistoric environment. Pictured, Laminated black shales and cherts exposed on the Peel River in the Yukon, Canada, that were deposited during the late Ordovician and earliest Silurian and show no evidence of life

The researchers looked specifically at the second pulse of extinction to find out exactly how low oxygen levels were, how long for and where in the ocean.

Previous studies gleaned valuable information about ancient oxygen levels by looking at changes in radioactive metals caused by different levels of the gas.

Using this information and new data from samples of black shale from the Murzuq Basin in Libya, Mr Stockey and colleagues created a new model to map out the oxygen levels in the prehistoric environment.

‘The model’s conclusion: In any reasonable scenario, severe and prolonged ocean anoxia must have occurred across large volumes of Earth’s ocean bottoms,’ Mr Stockey said.

‘Thanks to this model, we can confidently say a long and profound global anoxic event is linked to the second pulse of mass extinction in the Late Ordovician,’ said paper author and geologist Erik Sperling, also of Stanford University.

‘For most ocean life, the Hirnantian–Rhuddanian boundary was indeed a really bad time to be alive.’

The full findings of the study were published in the journal Nature Communications.

WHEN WERE EARTH’S ‘BIG FIVE’ EXTINCTION EVENTS?

Traditionally, scientists have referred to the ‘Big Five’ mass extinctions, including perhaps the most famous mass extinction triggered by a meteorite impact that brought about the end of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

But the other major mass extinctions were caused by phenomena originating entirely on Earth, and while they are less well known, we may learn something from exploring them that could shed light on our current environmental crises.

Source: Read Full Article