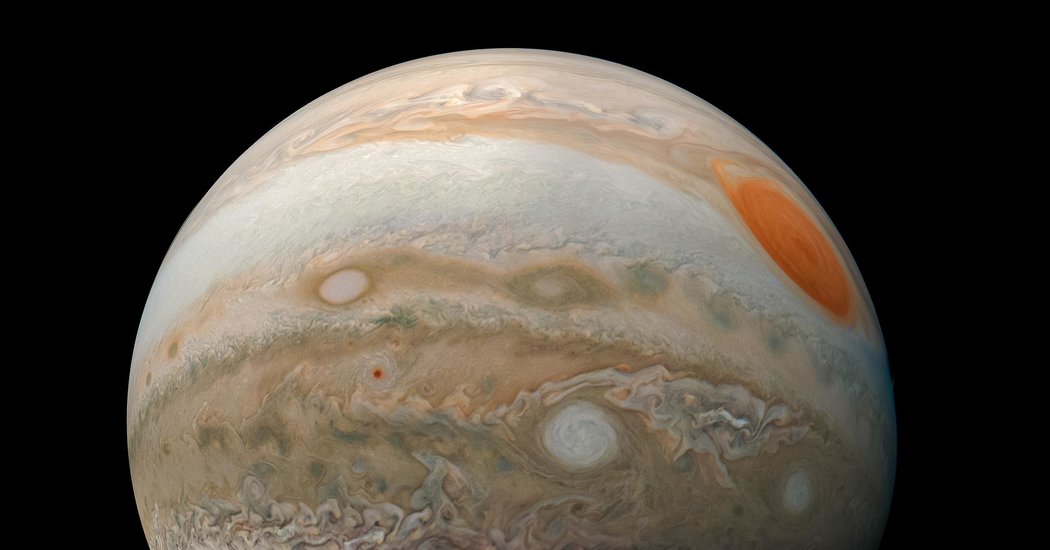

Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is shrinking, but that does not necessarily mean that it is dying.

Earlier this year, amateur astronomers caught the red spot seemingly starting to fall apart, with rose-colored clouds breaking away from the storm that is some 15,000 miles wide. In May, giant streamers of gas appeared to be peeling from the spot’s outer rim, blown into the winds circling the planet.

The spot — which is red for reasons not fully understood — has become smaller in recent decades. Some Jupiter-watchers wondered if they were witnessing the beginning of the Great Red Spot’s end.

“We beg to differ with that conclusion,” Philip S. Marcus, a professor of fluid mechanics at the University of California, Berkeley said on Monday during a news conference at a meeting of the American Physical Society’s division of fluid dynamics in Seattle. In essence, Dr. Marcus said, the odd dynamics in the spot are just the result of weather on Jupiter, the solar system’s largest planet.

Jupiter and Its Moons

Spinnable maps of Jupiter and the Galilean moons.

Robert Hooke, an English scientist, first reported an oval on Jupiter in 1664. The following year, Giovanni Cassini, an Italian astronomer, also observed a spot and he and others continued observing it until 1713. (Cassini died in 1712.) Then astronomers lost track of it for more than a century. That could mean Cassini’s spot disappeared and another one formed later, or it could mean that no one was looking carefully during that time. The current spot has persisted for at least 189 years, and probably for centuries before that.

The Great Red Spot is an anticyclone — a high-pressure system that, because it is in the southern hemisphere, rotates in a counterclockwise direction. That makes it unlike hurricanes and other large storms on Earth, which are low-pressure weather systems, or cyclones, that rotate in the opposite direction of anticyclones. Cyclones also exist on Jupiter, but the warm air at the centers of Jovian cyclones often forms wispy clouds, or no clouds at all.

Thus, just looking at the clouds of Jupiter is sometimes misleading, missing the effects of unseen cyclones.

The clouds, at the top of Jupiter’s atmosphere, do not necessarily tell what is going on deep down, hundreds of miles below the Great Red Spot in the vortex that drives the storm.

“You can’t just conclude that if a cloud is getting smaller that the underlying vortex is getting smaller,” he said.

Through computer simulations, Dr. Marcus and his colleagues have been studying the dynamics of the Great Red Spot and other Jovian anticyclones.

The clouds of anticyclones do not always match the boundaries of the underlying vortex. But they also give clues to nearby cyclones.

The simulations indicate a coincidence of two phenomena accounts for the odd dynamics of the Red Spot. Every decade or so, a cyclone comes close to the Great Red Spot and the winds of the two systems collide and deflect at an angle.

“It’s like having two fire hoses aimed at each other,” Dr. Marcus said.

At the same time, the storm was merging with a smaller anticyclone, the deflected winds from the collision with the cyclone carved off pieces of the merging anticyclone. That formed the blade-shaped clouds that were seen separating from the spot, Dr. Marcus said.

He added that the event was just part of the normal dynamics of Jupiter. The Great Red Spot, he predicts, will live “for the indefinite future” — likely centuries longer.

“Of course, I probably just gave it the kiss of death,” Dr. Marcus joked, “and it’ll probably fall apart next week.”

Source: Read Full Article