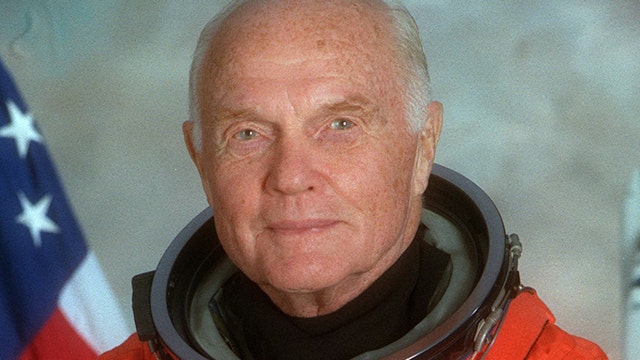

Life and times of John Glenn

The war hero was the first American astronaut to orbit the Earth and one of the most successful politicians on Capitol Hill

Sunday marks 60 years since NASA astronaut John Glenn became the first American to orbit Earth.

On Feb. 20, 1962, the “Mercury Seven” member set out on the agency’s three-orbit Mercury-Atlas 6 mission aboard the spacecraft he named Friendship 7.

New images released to Fox News show the mission – and Glenn – in remarkable detail.

The pictures, created by “Apollo Remastered” author Andy Saunders, were made using source footage provided by Stephen Slater, who headed up the archive research and production for “Apollo 11.”

Saunders, who has previously shared remastered images of the Apollo 15 moon landing, regularly posts new images on Twitter and Instagram.

To produce each new image, Saunders told Fox News he stacked hundreds of frames of the film on top of each other in several areas of the film — “averaging out” the image noise — and “stitched” the frames together, with each image containing more than 1,000 image samples. The output was then constructed using digital processing techniques.

Glenn can be seen waiting for launch for more than two hours before the space flight as well as in orbit, watching the booster and the curvature of Earth.

According to NASA, an initial launch attempt on Jan. 27 was postponed due to thick clouds that would have prevented observation of the rocket’s ascent.

Mechanical and weather problems added further delays.

Glenn observes his booster falling away against the curvature of Earth through the capsule window, signifying the moment he had reached orbit.

(NASA/Andy Saunders; Digital Source: Stephen Slater)

Glenn boarded the capsule at Launch Complex 14 of what is now known as Florida’s Canaveral Space Force Station.

Following additional delays, and after nearly four hours in the capsule, the countdown reached zero at 9:47 a.m. EST, and the Atlas rocket’s three main engines ignited.

Four seconds later, the rocket rose above the launch pad and, two minutes and nine seconds after that, its two booster engines cut off and were jettisoned.

After continuing to operate on the power of its center-mounted sustainer engine, at five minutes and one second into the flight, the sustainer engine cut off, and Friendship 7 separated two seconds later.

Glenn was in orbit and Friendship 7 turned around, flying with its heat shield in the direction of flight.

Glenn snapped pictures and continued to report on his and the spacecraft’s condition, successfully controlling the capsule’s altitude and eating a tube of applesauce and a xylitol pill before he was given the OK for his second orbit.

As Glenn passed over Cape Canaveral during the start of his second orbit, controllers noticed a signal indicating that the spacecraft’s landing bag had deployed, meaning that the heat shield required for reentry was no longer in place.

Although engineers believed the signal was an error, they devised a plan to keep the retrorocket pack on after retrofire, with the aim of having the straps keep the heat shield in place.

Glenn, who was not told explicitly about the issue, was advised to ensure the landing-bag deploy switch was in the “off” position.

He was given the green light to proceed to his third orbit, and controllers instructed Glenn to place the landing-bag switch in the automatic position and keep the retropack in place after retrofire if a light should come on.

Glenn reported he hadn’t heard bumping noises during attitude maneuvers that would indicate a deployed landing bag.

Close to California, the spacecraft fired its three retrorockets to slow its velocity, and engineers closely monitored Friendship 7’s reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere.

As planned, a temporary radio blackout lasting four minutes and 20 seconds occurred as the spacecraft sped through the upper atmosphere, and Glenn described reentry as a “real fireball outside” while pieces of the retropack burned off.

He manually controlled the spacecraft’s altitude and, eventually, exhausted its fuel supply.

Glenn holds steadfast as he observes the retro pack burn up outside his window.

(Credit: NASA/Andy Saunders; Digital Source: Stephen Slater)

At 28,000 feet, the drogue parachute deployed early, and at 10,800 feet the main 63-foot red and white main parachute followed suit.

Friendship 7 splashed down in the vicinity of Grand Turk Island at 2:43 p.m. EST.

Glenn’s flight lasted for four hours, 55 minutes and 23 seconds.

The closest vessel, the destroyer U.S.S. Noa, completed the retrieval from the water, and the recovery operation took 21 minutes

Glenn blew the side hatch, and doctors escorted him to the ship’s sick bay for a medical examination. He was then flown to Grand Turk Island, arriving there about five hours after splashdown.

Later, President John F. Kennedy presented him with the NASA Distinguished Service Medal.

Following a tour on Feb. 23, 1963, NASA formally passed Friendship 7 to the Smithsonian’s Institution in Washington, D.C.

When he was 77 years old in 1998, Glenn got a chance to fly again with six astronauts aboard the STS-95 Discovery shuttle flight.

Glenn, who was born in Ohio July 18, 1921, later became a U.S. senator and served in that role for 25 years. He also worked with college students at Ohio State University.

Glenn was a Marine pilot during World War II, fought in the Korean War and became an airplane test pilot, setting a speed record in 1957 during a flight from Los Angeles to New York that took less than 3.5 hours.

He died in Columbus, Ohio, Dec. 8, 2016, at the age of 95.

Source: Read Full Article