David Attenborough explores 'very exciting picture'

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

In 2017, two amateur archaeologists, Sally and Neville Hollingsworth, made an incredible find at Cerney Wick quarry, just outside of Swindon. They came across an enormous bone belonging to a mammoth dated from around 215,00 years ago. It was, in other words, something you might expect to find in Siberia, not south west England.

Sir David chronicled the discovery in his BBC documentary, ‘Attenborough and the Mammoth Graveyard’, exploring which species of mammoth — steppe or woolly — once explored this part of suburbia, and after the discovery of ancient stone tools was made at the site, whether humans once lived alongside them.

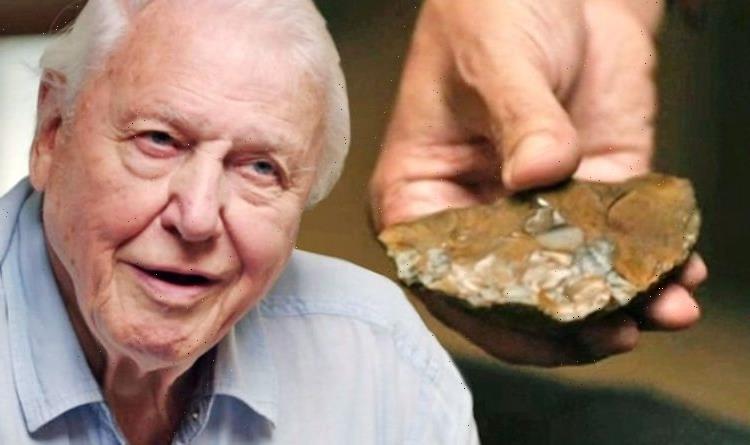

One aspect of this ancient human journey saw Sir David visit a secure facility in London ‒ part of the British Museum which holds one of the largest collections of prehistoric artefacts in the world.

Here, Professor Nick Ashton, its curator and a renowned expert on ancient stone tools, was recruited to analyse the piece found at Cerney Wick.

His explanations led them to the intricate and historic relationship between humans and fire, with Sir David commenting on the “exciting picture” that Prof Ashton painted.

Humans, it is believed, spread out of Africa around two million years ago.

A million years later, some of their descendants reached Britain.

We know very little about them and other prehistoric people because most of the evidence for their existence has since decomposed and disappeared.

But, their stone tools remain and reveal the remarkable story of early humans spreading from Africa throughout Northern Europe.

JUST IN: Egypt news: ‘Strange’ spots discovered in Tutankhamun’s tomb explained

By 500,000 years ago, humans in Britain were capable of crafting hand-axes like the one found at Cerney Wick, and would have used the items to hunt things like deer.

Humans first used fire in Africa, and by 400,000 years ago were using it in Northern Europe as well.

Prof Ashton, presenting a piece of stone tool that appeared singed, said: “This is a burnt flint; it’s a block of flint that shattered under heat.

“What we think we’re dealing with is a small campfire, which has all kinds of benefits.

DON’T MISS

Northern Lights show TONIGHT – aurora borealis visible in Shropshire [REPORT]

Solar storm warning: Earth to be battered this weekend [INSIGHT]

Scientists discover new approach to beat antibiotic-resistant bacteria [ANALYSIS]

“It’s not just warmth, it’s not just keeping away the big cats, it’s also a hub for social life.

“It extends your daylight hours into the night, it means you begin to tell stories, it’s all part of the development of language and those all-important social bonds that make us human.”

In response to this, Sir David said: “You paint a very, very convincing picture, actually, and anyone who has sat by a fire knows how hypnotic it can be.

“Just sitting there watching the flames.

“That’s a very exciting picture.”

Prof Ashton sifted through the institute’s large collection of stone tools, first laying out some simple flint tools found near Happisburgh on the east coast of England.

Researchers know that ancient humans had been making stone tools for some two to three million years before they reached Europe.

The earliest evidence available of humans using these tools in Europe dates to 900,000 years ago.

This also doubles up as the earliest evidence for humans in Northern Europe.

The species of human in Europe at that time was Homo Antecessor who would have looked very similar to modern-day humans.

In 2013, Prof Ashton’s team made a truly extraordinary discovery at Happisburgh after a storm washed away sand on a beach and revealed ancient footprints set in mud, the oldest human footprints ever documented outside of Africa.

But, within two weeks they had vanished, washed away by incoming tides, showing just how difficult it is to find and keep traces of our ancestors.

Source: Read Full Article