Supervolcano eruption in Sumatra 75,000 years ago led to a catastrophic drop in atmospheric ozone levels and a ‘bottleneck’ in the human population which fell to just 10,000–30,000, study finds

- The Toba super-eruption was first linked to the human bottleneck back in 1993

- However, evidence to support this controversial connection had proved elusive

- Researchers modelled the impact of the supervolcano on global ozone levels

- Volcanic aerosols block sunlight, cooling the Earth but slowing ozone formation

- The team found that Toba’s SO₂ emissions depleted ozone levels by 50 per cent

- This would have allowed UV radiation in the tropics to reach harmful levels

A catastrophic drop in atmospheric ozone levels around the tropics some 75,000 years ago caused a bottleneck in the human population, a study concluded.

Ozone levels fell by half as a result of the eruption of the Toba supervolcano in Sumatra, experts from Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Chemistry found.

One of the Earth’s largest-ever explosions, Toba is believed to have erupted some 5,097 square miles of material and triggered a 6–10 year ‘volcanic winter’.

Lake Toba — a 436 square mile body of water — has formed to fill the cauldron-like hollow, or ‘caldera’, left behind by the vast explosion.

The cooling from the volcanic winter would have had various knock-on effects including cooler oceans, longer El Niño events, crop failures and disease.

But by blocking out the sun and thus preventing protective ozone formation, ultraviolet radiation would have harmed humans more in the tropics, the team said.

According to past studies, the human population is believed to have fallen to just some 10,000–30,000 individuals in the wake of the Toba eruption.

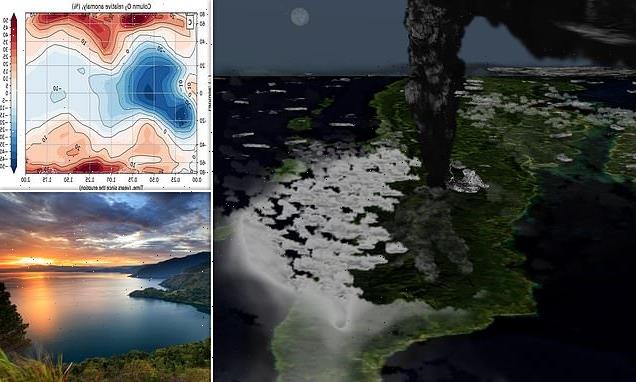

A catastrophic drop in atmospheric ozone levels around the tropics 60,000–100,000 years ago caused a bottleneck in the human population, a study concluded. Ozone levels fell by half as a result of the eruption of the Toba supervolcano in Sumatra, experts from Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Chemistry found. Pictured: an artist’s impression of the Toba eruption

What was the Toba catastrophe?

The Toba super-eruption was the biggest volcanic blast on Earth within the past 2.5 million years.

It blew its top on what is now the Indonesian island of Sumatra around 74,000 years ago.

The volcano fired out some 720 cubic miles (3,000 cubic km) of rock and ash which spread across the globe.

Some scientists believe the eruption blotted out the sky, bringing with it a volcanic winter that lasted a decade.

An eruption a hundred times smaller than Mount Toba – that of Mount Tambora, also in Indonesia, in 1815 – is thought to have brought a year without summer in 1816.

Toba’s eruption devastated life on Earth because its thick cloud of ash blocked out the sun, killing off much of the planet’s plantlife.

The event was so massive all that is left of the mountain is the enormous Lake Toba, which stretches 62 miles (100 kilometres) long, 19 miles (30 km) wide, and up to 1,657 feet (505 metres) deep.

The notion that the super-eruption was to blame for slowing the growth of human populations was first suggest by science writer Ann Gibbons in 1993.

‘Toba has long been posited as a cause of the bottleneck,’ explained paper author and atmospheric chemist Sergey Osipov from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz, Germany.

Yet, he added, ‘initial investigations into the climate variables of temperature and precipitation provided no concrete evidence of a devastating effect on humankind.’

Now, however, the link between the supervolcano and the bottleneck may have been established, said paper co-author and earth scientist Georgiy Stenchikov of the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST).

‘We point out that, in the tropics, near-surface ultraviolet (UV) radiation is the driving evolutionary factor,’ he explained.

Climate effects, such as the cooling caused by volcanic aerosols in the atmosphere blocking incoming sunlight, only become more relevant ‘in the more volatile regions away from the tropics,’ Professor Stenchikov added.

‘The ozone layer prevents high levels of harmful UV radiation reaching the surface,’ explained Dr Osipov.

‘To generate ozone from oxygen in the atmosphere, photons are needed to break the O₂ bond. When a volcano releases vast amounts of sulphur dioxide (SO₂), the resulting volcanic plume absorbs UV radiation but blocks sunlight.’

This, he added, ‘limits ozone formation, creating an ozone hole and heightening the chances of UV stress.’

In their study, the researchers ran a NASA-developed climate model on a KAUST-based supercomputer to simulate the impact of various eruption sizes on global levels of ultraviolet radiation.

Their modelling found that even relatively small super-eruption scenarios resulted in significant effects on atmospheric ozone, and that the estimated sulphur dioxide emissions from Toba likely depleted global ozone levels by up to 50 per cent.

This shift would have led to higher UV radiation levels reaching the Earth’s surface, increasing the harms to human health and negatively affecting survival rates.

‘The ultraviolet stress effects could be similar to the aftermath of a nuclear war,’ explained Dr Osipov.

Lake Toba — a 436 square mile body of water — has formed to fill the cauldron-like hollow, or ‘caldera’, left behind by the vast explosion. Pictured: the location of Lake Toba in Sumatra

One of the Earth’s largest-ever explosions, Toba is believed to have erupted some 5,097 square miles of material and triggered a 6–10 year volcanic winter. Pictured: Lake Toba, which fills the cauldron-like hollow, or caldera, left behind by the eruption, as seen in the present

‘For example, crop yields and marine productivity would drop due to UV sterilization effects. Going outside without UV protection would cause eye damage and sunburn in less than 15 minutes.’

‘Over time, skin cancers and general DNA damage would have led to population decline,’ he concluded.

The full findings of the study were published in the journal Communications Earth and Environment.

Source: Read Full Article