By Chip Le Grand

Credit: Marija Ercegovac

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

The morning after Daniel Andrews was first elected Victorian premier, he swiped through the door at No.1 Treasury Place and got down to work. Although journalists were invited there to record the moment, it wasn’t just for show. Since that day and nearly every day in office, Andrews governed at a breathless, unrelenting pace.

The evidence of his nine years in power is there for everyone to see: the enormous tunnels and sky rails and freeway expansions; the immense changes to social policy; the electoral marginalisation of the opposition parties; debt on a scale beyond anything previously racked up by a state government in Australia.

Yet, when Andrews finishes as premier at 5pm on Wednesday, one of his most profound legacies will be largely hidden from public view. To govern as he did, Andrews forced a radical alteration to the way the Victorian government operates. He did not merely lead his government – he bent it to his will.

“Andrews operated like the executive chairman of the state, with a huge capacity to consume and command the detail of diverse issues,” said Chris Eccles, the man chosen by Andrews to run, reshape and oversee the Victorian Public Service to deliver his government’s agenda.

“There was an enormous breadth in the reform landscape, with very few areas of economic and social policy untouched. There was a lot of stuff going out the door and when you run that hot with that bias towards action, there are real consequences for how you govern.”

Eccles is in a unique position to reflect on the Andrews government. He joined the state government after running the public service in both NSW and South Australia. Before he resigned as Department of Premier and Cabinet secretary in late 2020, he had become one of the premier’s closest political confidants.

Since he retired, he has considered at length what the Andrews government did well and where it was challenged, particularly in the heady days of its reform-heavy first term in office. On the day Andrews announced his retirement from politics, Eccles agreed to share his reflections with this masthead.

He described an “exponential increase” in the volume of activity and pace and cadence of government, which began as soon as Andrews began work on that Sunday after the 2014 election. That pace never slowed to ordinary levels.

Andrews, in announcing his retirement, admitted he was “worse than a workaholic” and consumed by the job. “There are two types of people,” he explained. “There are people who fixate on these things. They don’t tend to build a legacy, they are all about themselves. I’ve always been about the work. Work hard, then work harder again, and the results will speak for themselves.”

Numbers provided by Eccles show how the premier’s mantra was reflected in the legislation passed and money spent by the government under his watch. The government worked hard, then worked harder again. It spent big, then spent bigger again.

Throughout the comparatively plodding four years of the Baillieu and Napthine governments, the average annual funding for new initiatives was $5.2 billion, an average of $5.5 billion was invested in infrastructure, and total government expenses were running at $42.8 billion.

In the first term of the Andrews government, average annual funding on new initiatives reached $8.8 billion, infrastructure spending topped $10 billion, and total government expenses totalled $78.6 billion. At the same time, the volume of legislation increased from 2500 pages in 2014-15 to 6000 pages by 2017-18.

To push through this extraordinary volume of work, Andrews changed how government decisions were made, how the public service was structured and how the state budget was accounted for. Instead of cabinet being a place where prospective policy was subjected to robust debate, Andrews preferred for policies to be developed elsewhere and presented to cabinet for approval.

The engine room of the Andrews government was not the cabinet room. Instead, Andrews established a series of subcommittees, which he chaired, to do the government’s heavy lifting on policy development. The other members of cabinet quickly came to understand that every major policy presented to them already had the support of the premier. What the premier wanted, Victoria invariably got.

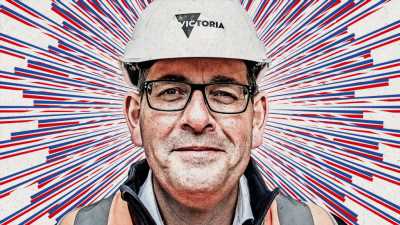

Daniel Andrews at the press conference announcing he is stepping down as premier.Credit: Jason South

The furious pace that Andrews demanded of government stretched the capacity of usual budget processes to keep up. In 2015-16, only 1.5 per cent of new funding initiatives were not included in that year’s state budget. By 2017-18, 18 per cent of new funding was booked outside the annual budget.

At the same time, the Victorian Public Service started to resemble a surge workforce, with a dramatic increase in the number of new bureaucrats brought in on one-year and two-year contracts and a doubling of the money spent on consultants. Throughout the first term, nearly $1 billion was spent on consultants commissioned for infrastructure projects.

Before the first COVID-19 case emerged in Wuhan, the Victorian government was already operating at something akin to an emergency setting. Andrews knew five years ago that this wasn’t sustainable.

Eccles said a sliding-doors moment came after the government was returned with a thumping majority at the 2018 election. Recognising frustrations around his own cabinet table and the need to rein in government spending, Andrews loosened cabinet discussions and authorised a series of internal government reviews, overseen by senior Department of Premier and Cabinet and Treasury officials, designed to reduce expenditure.

Before the product of those reviews could be implemented, Victoria was engulfed in flames and then plagued by COVID-19.

“There was a comprehensive whole-of-government review of expenditure in 2019, to be followed by planned rationalisation and adjustment for the 2020-21 budget,” Eccles said.

“Then came the bushfires and the pandemic. It would have been fascinating to see the outcome if the approach had been implemented without the intervention of the pandemic.”

A government already red-lining was plunged headlong into the worst public health crisis in a century. Eccles said the effect was to supercharge the defining characteristics of the Andrews government.

The COVID crisis was a sliding-doors moment for the government.Credit: Wayne Taylor

“Everything was heightened and taken to an extreme,” he said. “It exaggerated all the features of what, I think, was a highly successful government; the dominance of the principal and the speed to policy and program outcome.”

The consequences of this, and the missed opportunity for Andrews to reset his approach, will be felt for years in Victoria.

A senior Victorian business figure, speaking anonymously for fear of government reprisals, posed a question that will loom large in the remaining life of this state government and whatever government follows.

“How exactly is the state going to grow out of $175 billion of debt? All the assets have been sold, the state is in structural deficit. This is the worst Victorian government by the length of the Flemington straight,” they said.

A more measured assessment is that any state premier, no matter how extraordinary their capacity for hard work, needs to operate within the limits of good government. Andrews was determined to set his own.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.

Most Viewed in Politics

Source: Read Full Article