Julie Akins, a freelance journalist based in Ashland, Oregon, began a life-changing road trip in August 2016. Off and on over the course of the next two years, she pitched her tent and lived among homeless people from Portland to Denver.

Fascinated by the working homeless, Akins asked what they needed to get off the streets as she chronicled their stories for the book she’s writing, One Paycheck Away.

Then Akins noticed families living in school buses. Curious, she knocked on the door of an old blue school bus and met a family with seven children living inside. They had ripped out the seats and put down floors. There were mattresses on the floor, tubs full of clothes and a stacked bookcase.

“It was in disarray,” says Akins, 58. “There was no toilet, shower or kitchen.”

The father had gotten too sick before he could complete the renovation and was in hospice care when Akins met the family.

After meeting other families who found homes in the buses, she came up with the idea to take retired school buses and convert them into nice, livable spaces with kitchens and bathrooms for working homeless families.

“They want to have a place to live that is their own, that’s safe — and they want to be mobile, so they can get better jobs,” says Akins.

RELATED: Doctor Brings ‘Solar Suitcases’ to ‘Light Every Birth’ in Hospitals Without Steady Electric

Akins launched the non-profit Vehicles for Changes about 18 months ago. The first family moved into a converted, tricked-out “Skoolie” about nine months later.

“This is a project that I really think can have an impact,” says Alex Daniell, 57, who has spent years designing and building tiny houses for the homeless in Eugene, Oregon, where he helped develop Opportunity Village and Emerald Village.

But Daniell believes refitting retired school buses may be a better idea than tiny houses. It’s more cost-effective, he says, because there’s less to build from the ground-up. Plus, the buses are mobile and won’t have to be hauled on a truck, so families looking for work can relocate.

“I’m hopeful,” he says of the concept.

He liked Vehicles for Changes so much, he asked if he could help. Now he’s working on designing and building their next two buses with the assistance of a team of volunteers.

The Flood family had fallen behind on their rent. David Flood, 63, was working as a substitute teacher and finishing a master’s degree in interdisciplinary studies at Southern Oregon University. (Flood says he holds master’s degrees in both language arts and mental health counseling.) Due to a series of health issues, his wife wasn’t working. They had lived in their two-bedroom, two-bath trailer for about 10 years, he says, and their landlord had been “very gracious” in the past about late rent. But this time she said no, and the family became homeless on June 24, 2018.

“What people don’t understand, is that even if someone has a little bit of income, they can end up on the street — even families,” says Flood.

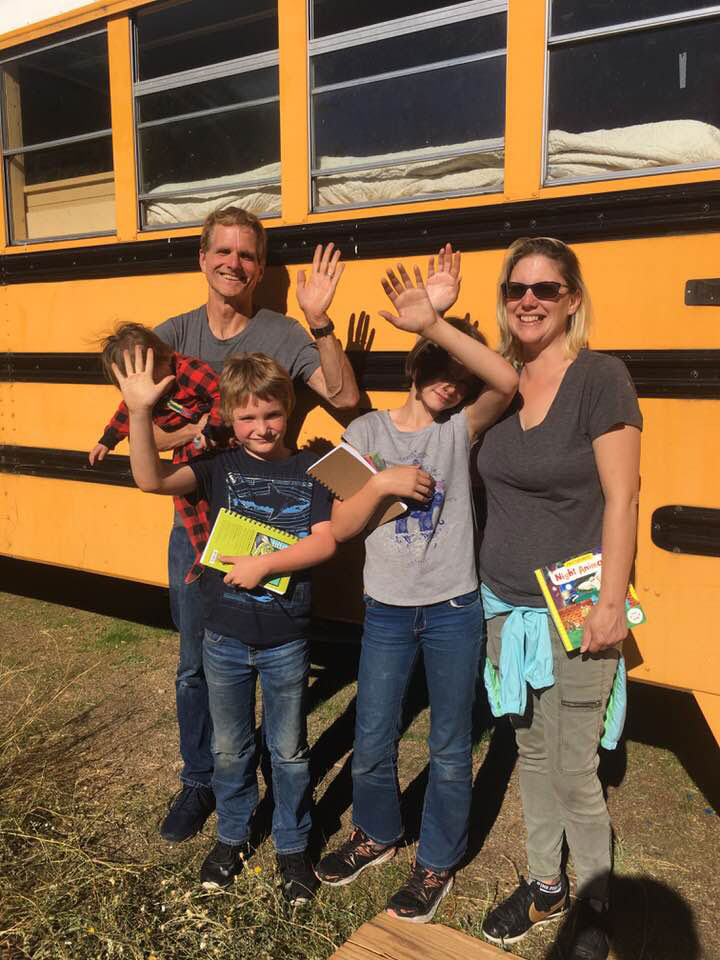

He and his 37-year-old wife, Jennifer, and their three kids — Raylee, 11, David Jr., 9, and Noah, 2 — lived in a tent at a campground through the summer, until it closed for repairs.

Then they lived in their silver 2006 Mercury Grand Marquis, alternating between a Walmart parking lot and rest stops. Worried as winter grew closer, he started thinking about driving to southern California.

Instead, his wife saw Akins on the news talking about her new non-profit and remembered that they had met Akins a few years ago, when they were all riding a city bus while Akins’ car was in the shop. The Floods applied, and on Thanksgiving Day last year, the family moved into their new home. Akins offered to paint the bus any color they wanted, but they insisted it stay yellow. They call it their “Yellow Submarine.”

“As a family, we used to always sing, ‘We all live in a Yellow Submarine,’” Flood says. “And that came true.”

The bus changed their lives, he tells PEOPLE. “It made the little money we had stronger,” he says. “It took the stress off of our lives. It allows us to breathe for a moment.”

His wife, Flood says, looks visibly less stressed. Looking forward, he hopes to finish his degree and get a job as an adjunct professor.

“It really is The Magic School Bus,” Akins says. “They’re in there learning all the time. David’s always learning a new thing and teaching his kids.”

They’ve planted an organic garden beside the bus, currently parked in a mobile home park in Ashland.

Rising third-grader David Jr., known to family and friends as “The Private,” enjoys playing basketball and running track. He loves hot dogs and catching crawdads. And he really loves his home.

“On the outside, it looks very small — and just like a plain school bus,” the boy says. “But it opens up on the inside. On the inside, it’s a mansion.”

When Akins blogged about her idea of starting a non-profit, a woman in Michigan — whom Akins has never met — asked for more information and eventually funded the non-profit for five years, giving $25,000 a year.

The current plan is to make one “Skoolie” a year. “But if I could raise more money and awareness, there’s no reason why we can’t make a lot more,” she says.

“What I’m pushing toward,” says Akins, is to make five per year.

Two more retired buses have been donated by a school district, and Daniell is working on them in Eugene.

“The idea of getting used, donated buses from schools and then converting them with volunteer labor — it’s very appealing to me,” Daniell says. “It’s so community-oriented.”

He plans to bring in volunteers from various church groups and ask artists and artisans to donate their time and talents to reimagine the insides.

“The end product results from keeping a family from breaking apart,” says Daniell, who wants to create a design that can be replicated by other organizations around the country. “My experience with the homeless is: if the families don’t get split apart, and the kids stay in school, they don’t end up on the street. Once somebody’s been on the street for a while, it’s hard to find their way back in.”

Source: Read Full Article