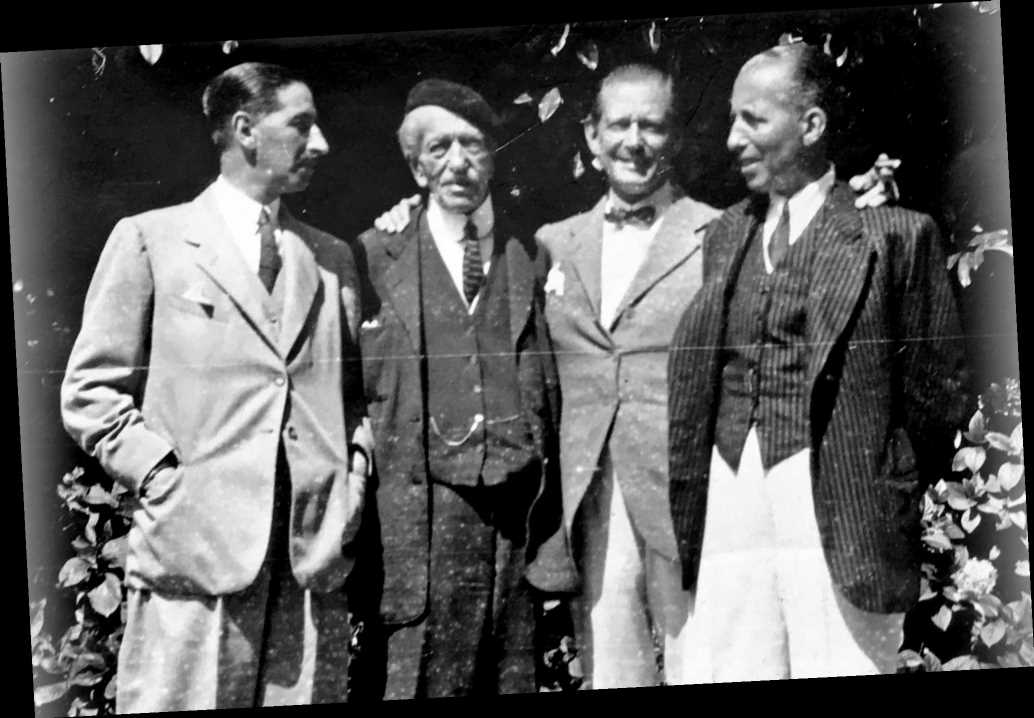

In the late 1890s, three brothers — Louis, Pierre and Jacques Cartier — sat hunched over a world map at their modest home in Paris.

The boys, then ages 18, 15 and 9, carefully split it into three key regions: Europe, the Americas and Great Britain. Louis, the eldest, assigned one area to each brother. Then, they joined together in a pledge “to create the leading jewelry firm in the world!”

The brothers knew that they would one day inherit the family business: a Paris-based jewelry store founded by their grandfather, Louis-Francois Cartier, in 1847. And they were already plotting to transform the shop from a local destination spot into an international luxury powerhouse, as detailed in the book “The Cartiers: The Untold Story of the Family Behind the Jewelry Empire” (Ballantine), out now.

Francesca Cartier Brickell, Jacques’ great-granddaughter and a former financial analyst, wrote the book after stumbling on a trunk full of hand-written letters while searching for a bottle of vintage champagne in her grandfather’s basement.

The treasure trove of correspondence sent her on a decade-long journey of discovery about her legacy.

Louis-Francois, Cartier’s founder, was a humble jewelry-store apprentice from a working-class background. As a young man, he scraped together the money to buy out his mentors when he learned they were moving on to a chicer part of town. For a generation, the family skated by, selling original jewelry designs as well as other fineries including porcelain dishware and vases.

But as the three grandsons came of age, they foresaw bigger opportunities for Cartier.

Louis was domineering as the oldest of four siblings (there was a little sister, too) and he gave himself the plum job of holding down Paris and the rest of Europe when he divvied up the map. But he compromised in other ways: He agreed to marry Andrée-Caroline Worth, the beautiful yet troubled granddaughter of Charles Frederick Worth, then one of the world’s leading couturiers. Louis’ father had arranged the match, knowing that a formal alliance with the esteemed dressmaker would be a boon to business.

But Louis resisted; it was clear to him that Andrée-Caroline, then just 16, was not well. “She wasn’t like other girls,” Brickell writes. “She was somber one minute, hysterical the next . . . he couldn’t help but judge her to be ‘ill of mind.’ ”

Still, he went ahead with the marriage. Not only would the match boost Louis’ social status, it was financially wise: Andrée-Caroline’s father was offering a dowry of 720,000 francs (the equivalent of $3.85 million today) as well as access to Worth’s top-notch international customers. Soon after the nuptials, the Cartiers moved their store to the Rue de la Paix, one of the leading shopping destinations in Paris and just down the street from the gleaming Worth showroom. That way, a wealthy woman on the hunt for a gorgeous gown didn’t have to go far if she wanted a brand-new bauble to go with it.

But Louis’ instincts about his wife turned out to be right: She remained erratic throughout their marriage. Because Louis didn’t care to spend much time at home, he became a regular at Parisian nightclubs, mingling with courtesans and the kind of reckless, extravagant men they attracted. These men — almost always married themselves — soon became some of Cartier’s best clients. “With almost every man came at least two opportunities for a sale,” Brickell writes. “A diamond necklace for his lover, perhaps, and a guilt-driven tiara for the unsuspecting, or aggrieved, wife.”

Louis even developed a special filing system at the store to accommodate such buyers, after one embarrassing mix-up where a store clerk asked the wife of a loyal client how she liked her new necklace. Her reaction said it all, and so Louis instituted a new policy where men’s purchase receipts were sorted by recipient. He understood that “discretion was crucial in this business,” Brickell writes.

Pierre, three years younger than his brother, also had a knack for anticipating the deepest desires of the elite.

“A born networker,” according to Brickell, Pierre joined the firm in 1900, with the intention of eventually expanding Cartier’s footprint to the United States, per the brothers’ original scheme. It helped when he fell in love with an American socialite, named Elma Rumsey, whom he met when she was shopping her way through Paris. Rumsey was the 33-year-old daughter of a St. Louis railroad tycoon and was representative of the new American upper crust. “The wealth of the New World was compounding at a phenomenal rate,” Brickell explains. “Self-made millionaires had riches to rival the royals and generally a wife and a daughter who were not shy about spending it.”

The pair wed in 1908 and not too long afterward, Pierre set his sights on opening Cartier in New York. Rumsey’s pedigree gave Pierre entree into a world of bankers, businessmen and American aristocrats; top Cartier client John Pierpont Morgan, who the brothers met through the Worths, helped him make connections, too.

Pierre then worked his network to advance the Cartier brand.

He personally wrote to influential men, suggesting they might want to familiarize themselves with a top European jeweler. He had business cards printed up to leave at the city’s most exclusive hotels, such as the Waldorf-Astoria. But it was two specific jewels — the Hope diamond and a very rare, double-strand natural pearl necklace — that secured Cartier New York’s status for future generations.

Cartier purchased the Hope diamond — an infamous, 45-carat, cornflower blue diamond — soon after Pierre moved to New York. The jewel was beautiful but controversial: Many people wouldn’t touch it, let alone buy it, because they believed that it was cursed. But “far from being put off by the curse, Pierre believed the gemstone’s notoriety could act in his favor,” Brickell writes. Sure enough, he soon offered it to a gem-obsessed, spendthrift socialite named Evalyn Walsh McLean. She was married to Ned McLean, then the irresponsible heir to the Washington Post fortune.

‘With almost every man came at least two sales — one for his lover and one for his wife’

The price was $180,000, or roughly $5 million today. A protracted, and very public, negotiation ensued. At one point, Evalyn tried to return the stone, but Pierre would not accept it. Meanwhile the story — of a well-known woman, an established European jeweler and a cursed diamond — became tabloid fodder. Ultimately, due to legal fees, Cartier lost money on the Hope, but Pierre understood that press was priceless. “Through this single transaction,” Brickell writes, “Cartier became a household name in New York.”

Years later, Pierre used a stunning, million-dollar pearl necklace ($24 million in today’s dollars) to snag a coveted piece of real estate.

Maisie Plant, who was married to transportation mogul Morton Plant, had admired the piece in the Cartier showroom one day so Pierre sprung into action and immediately tried to make the sale. Her husband claimed he couldn’t afford it, but he wanted to appease his wife so he was amenable when Pierre offered him a trade: the bauble for Plant’s mansion on Fifth Avenue and 52nd Street. Plant had been considering putting it on the market, so he agreed. That building became the regal Cartier townhouse.

“It wasn’t as absurd as it sounds today,” Brickell’s grandfather, Jean-Jacques Cartier, explains in the book. “Buildings, after all, could be built or rebuilt, but finding … enough good-quality, perfectly matched pearls for a necklace, well, that could take decades.”

Jacques Cartier — the youngest brother, who was the least interested in jewelry at first — ultimately forged his own lasting contributions to the family business, too.

Growing up, Jacques had aspired to be a Catholic priest. But that changed when he met Nelly Harjes, an heiress whose father worked with J.P. Morgan. The Cartiers were thrilled with the match, but Nelly’s family was underwhelmed, to say the least. They regarded the Cartiers “as shopkeepers, or ‘mere trade,’ ” Brickell writes. Nelly begged her father to sanction the marriage, but he remained doubtful of Jacques’ suitability.

Ultimately, John Harjes proposed a plan: If Nelly and Jacques could go a year without seeing each other, and still wanted to be together at the end, he would allow it. To distract himself during their prolonged separation, Jacques — who joined Cartier in 1906 — became utterly devoted to his work. His piece of the global puzzle was England and the colonies, and he traveled to India, making connections with gem-loving maharajas and immersing himself in the jewelry there, which ultimately informed Cartier’s signature, Eastern-inflected aesthetic.

After Jacques and Nelly reunited, they were happily married, with her father’s blessing, and the pair made a substantial impact on the Cartier legacy in 1919.

That year, they had a son: the first boy of his generation to carry on the family name. Pierre was delighted, and sent a cheerful, congratulatory letter to his brother.

“At last a boy!” he wrote. “Love to Nelly, must write news in social column.”

Source: Read Full Article