If you purchase an independently reviewed product or service through a link on our website, SheKnows may receive an affiliate commission.

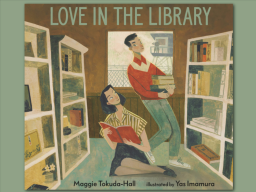

Like any children’s book author would be, Maggie Tokuda-Hall was thrilled at the news that Scholastic — arguably one of the most prominent publishing houses in the industry — wanted to license her book, Love in the Library, and feature it in an Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander (AANHPI) narratives collection. The book, for kids ages 6-9, follows the story of her real-life grandparents, Tama and George Tokuda, whose beautiful WWII-era love story blossomed in the unlikeliest of places: Japanese American incarceration camp Minidoka. Gorgeously illustrated by Yas Imamura, it’s a story of hope amid adversity. But also, and perhaps more importantly, it’s a reminder of a hard truth: the fact that, in 1941, 120,000 Japanese Americans were wrongfully and cruelly imprisoned simply because they were Japanese.

“[A]s soon as I cleared the opening paragraph, my heart sank,” Tokuda-Hall wrote of Scholastic’s invitation on her blog, Pretty OK Maggie. Because this invitation came with a very telling clause: Scholastic wanted Tokuda-Hall to erase any mention of racism — even the word “racism” itself — from the accompanying author’s note.

-

A Glaring Omission

Image Credit: Courtesy of Maggie Tokuda-Hall As shown on Tokuda-Hall’s blog, Scholastic’s proposed edits were essentially an attempt to take out the most uncomfortable-but-necessary part. The paragraph they wanted to strike read as follows:

“As much as I would hope this would be a story of a distant past, it is not. It’s very much the story of America here and now. The racism that put my grandparents into Minidoka is the same hate that keeps children in cages on our border. It’s the myth of white supremacy that brought slavery to our past and allows the police to murder Black people in our present. It’s the same fear that brings Muslim bans. It’s the same contempt that creates voter suppression, medical apartheid, and food deserts. The same cruelty that carved reservations out of stolen, sovreign land, that paved the Trail of Tears. Hate is not a virus; it is an American tradition.”

But that’s not all. Scholastic’s suggestion was to exclude the word “racism” from the author’s note entirely.

“They wanted to take this book and repackage it so that it was just a simple love story. Nothing more,” said Tokuda-Hall. “Not anything that might offend those book banners in what they called this ‘politically sensitive’ moment.”

-

Book Banning Runs Rampant

Image Credit: Getty Images According to NPR, 2023 is on track to beat last year’s book-banning record: “The free speech group PEN America counted 2,500 instances of book bans in U.S. schools during the 2021-22 academic year.” This especially disheartening when you consider that, per The New York Times, 2022’s banned book pace nearly doubled that of 2021. Conservative advocacy groups such as No Left Turn in Education are fueling the bans with claims that these books are “used to spread radical and racist ideologies to students.”

Suzanne Nossel, Chief Executive of PEN America, noted to the Times that these groups “have essentially weaponized book lists meant to promote more diverse reading material, taking those lists and then pushing for all the included titles to be banned.”

-

Fighting Back

Image Credit: Twitter/Maggie Tokuda-Hall It was in light of this that Tokuda-Hall decided to make the public aware of Scholastic’s astonishing request, even though it was a scary prospect.

“I waffled a bit, deciding if I wanted to talk about this in public,” she wrote on her blog. ” … And I would be lying if I didn’t admit I am afraid, deeply afraid. That this will negatively impact my career in some irrevocable way. That I’ll be labeled as too sensitive or a primadonna. I am aware that reputations matter. I am aware people have faced worse. And I’m tired, and I’d rather not do any of this. It’d be easier not to.”

But it was an issue that’s far too important to ignore, so Tokuda-Hall decided to publish the proposed edits from Scholastic, in addition to the contents of the letter she sent them, which read in part: “What is particularly boggling to me about this offensive offer is that — in so many bans — books about Japanese Incarceration are included. Baseball Saved Us: banned. They Called Us the Enemy: banned. Regardless of any commentary like mine, our stories have already been deemed dangerous. There’s no appeasing those that would ban this book anyway. So to come to me, and to dangle this amazing opportunity, but to do so at this terrible price? To me it communicates that [Scholastic has] chosen their side. And it isn’t mine. Years from now when they ask themselves what they did in this time of rising book bans, I hope they remember this moment. I know I will.” (You can read Tokuda-Hall’s letter in its entirety on her blog here.)

-

The Irony is Real

Image Credit: Twitter/Scholastic Ironically, in March 2021, Scholastic’s official Twitter account tweeted the above statement from Chairman & CEO Dick Robinson, outlining how they “denounce all acts of bigotry and racism” and promise to “continue to amplify diverse stories and creators.” Given their request to Tokuda-Hall, however, this seems almost performative. SheKnows reached out to Scholastic for comment, but at press time, they had not responded.

“The irony of curating a collection tentatively titled Rising Voices: Amplifying AANHPI Narratives with one hand while demanding that I strangle my own voice with the other was, to me, the perfect encapsulation of what publishing, our dubious white ally, does so often to marginalized creators,” wrote Tokuda-Hall. “They want the credibility of our identities, want to market our biographies. They want to sell our suffering, smoothed down and made palatable to the white readers they prioritize. To assuage white guilt with stories that promise to make them better people, while never threatening them, not even with discomfort. They have no investment in our voices. Always, our voices are the first sacrifice at the altar of marketability.”

-

Lifting Up ‘Love’

Tokuda-Hall’s grandparents’ tale is as much about their unjust circumstances as it is about their love story, and it deserves to be seen and heard for all its facets — not just the comfortable, non-offensive parts. Because, like every book that’s banned or challenged, it brings truths that are not always easy to swallow — but our children deserve to know, so that they can do better.

Booklist said of Love in the Library: “The author’s gentle text captures the resilience of human dignity and optimism even during times of immense challenge and adversity. Imamura’s stunning gouache and watercolor illustrations convey both the setting and the emotions of the characters …Tokuda-Hall’s author’s note discussing her grandparents, Japanese internment camps, and the continuing impact of racism caps off this powerful must-read.” Bookpage said that Love in the Library “tells a love story for the ages without sugarcoating history.” And Kirkus Reviews called it “An evocative and empowering tribute to human dignity and optimism.”

Love in the Library by Maggie Tokuda-Hall$12.60on Amazon.com

Buy nowWe sincerely hope that Scholastic rethinks its stance on Tokuda-Hall’s author letter (though by now, it may be too little, too late), and admire Tokuda-Hall for bravely shining a light on a problem that all too often gets swept under the proverbial rug.

“Every time I see a marginalized creator tell the truth about what they face, I feel this way: frustrated. Furious. Disheartened. But also less alone,” she wrote.

“Each incident reminds me that we are braver than they are, even if it’s only because we have to be. And that the more of us who do this, the more likely there may come a day when we can stop doing this.”

Source: Read Full Article