During a recent trip to New York, Dave Asprey, 44, put ice packs on his body right before bed. The founder and CEO of Bulletproof, a company that sells coffee and supplements aimed at helping people “perform better, think faster, and live better,” Asprey had read research concluding that lowering body temperature is linked to improved sleep quality. He figured putting ice packs on his body would be a good substitute for taking an ice bath before bed, which he had previously tried with some success.

He was wrong.

“I ended up getting ice burns on about 15 percent of my body,” Asprey told MensHealth.com. “It hurt like crazy for weeks. That was definitely an experiment that didn’t work.”

Getting more sleep is a problem that has confounded people for centuries. The first recorded reference to insomnia dates back to Aristotle’s writings in ancient Greece in 350 B.C., and historical figures from Abraham Lincoln to Vincent van Gogh reportedly struggled with the condition. The issue has only been exacerbated by our modern work and screen obsessed culture, which requires employees to be glued to their phones late into the night. The Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) estimate that one in three adults doesn’t get enough sleep, even though sleeping for less than seven hours a day has been linked to health problems like obesity, high blood pressure, heart disease and stroke.

In light of the extensive body of research linking sleep to other areas of health and fitness, Asprey and other high-powered Silicon Valley CEOs have devoted themselves to biohacking their own sleep habits to achieve optimum performance. Biohacking is a term used to describe essentially conducting experiments on yourself outside of a traditional medical or research setting (hence, the ice pack experiment). It’s a broad term that has been used to describe everything from taking supplements to implanting a vibrating motor in your penis. But the overall aim is to become healthier, more efficient, and overall just better.

In general, Asprey says that he has spent more than $1 million on his biohacking efforts. He estimates that $200,000 of that sum has been spent on hacking his sleep. Unlike most medical experts, he eschews traditional wisdom that quantity is important when it comes to sleep (i.e., how many hours of shut-eye you get per night), citing research suggesting that sleeping only six hours a night can increase longevity.

“The conclusion is that people who are healthy need less sleep,” he says. “Anytime you can increase your resilience and human performance, it improves sleep.”

That’s why Asprey is more focused on sleep quality, which he hopes will reduce how many hours he needs to sleep, thus maximizing his productivity. He says he sleeps six hours and five minutes per night.

“Wouldn’t it be cool if getting healthy got you more hours every day?,” Asprey says. “That’s the mindset that I’ve had. Because we don’t all want to sleep.”

The aim is to become healthier, more efficient, and overall just better.

When Asprey tried it more than 20 years ago, he found it unsuccessful. “You have to be a perfectionist when you do it, and it takes a lot of energy to be a perfectionist with your sleep,” he says. “You can’t go to lunch with your friends. You can’t go on a date. You have to look at your watch and say, ‘Guys, I gotta go.'”

Asprey has tried countless other methods, including sleeping on a magnetic pad, which he says contains powerful magnets that help the mitochondria in his body better “power the system and provide more restful sleep.” (Whatever it does, it’s expensive: one such invention, the Magnetico sleep pad, retails at $510.)

He has also tried transcranial electrical stimulation, which requires putting electrodes behind each ear lobe and running a small amount of electricity between the ears. Asprey says he uses this technique to enhance delta sleep, or stage-3 sleep, the deepest sleep phase. “I run the electricity to my brain to say, ‘Hey, brain, you’re going to be in delta sleep this entire time and you don’t have much choice about it,'” he explains.

With a hugely successful podcast and 126,000 followers on Instagram, Asprey may be one of the most famous biohackers in the world. But he’s far from the only Silicon Valley mogul spending thousands of dollars to hack his own sleep. Geoffrey Woo is the CEO and cofounder of HVMN, a company that sells nootropics, or substances that claim to enhance mental performance — or, as it says on its website, “relentlessly pursue[s] human optimization.”

Woo began his adventures in biohacking five years ago, and admits he was initially drawn to it for selfish reasons. “I was like, ‘How can I be better than the people around me?'” he told MensHealth.com. In recent years, however, his stance has changed: “I wanna live in a society with healthier, happier, more productive human beings,” he explains.

Much of what Woo does to improve his own sleep aligns with conventional medical wisdom. He uses light-blocking curtains and a white noise machine to keep his bedroom quiet and dark, and he gets about eight hours of sleep per night, which falls squarely within current CDC recommendations. “It’s pretty clear to me that if I don’t get eight hours, my day sucks,” he says. “My heart rate variability and resting heart rate are much wonkier [without it].”

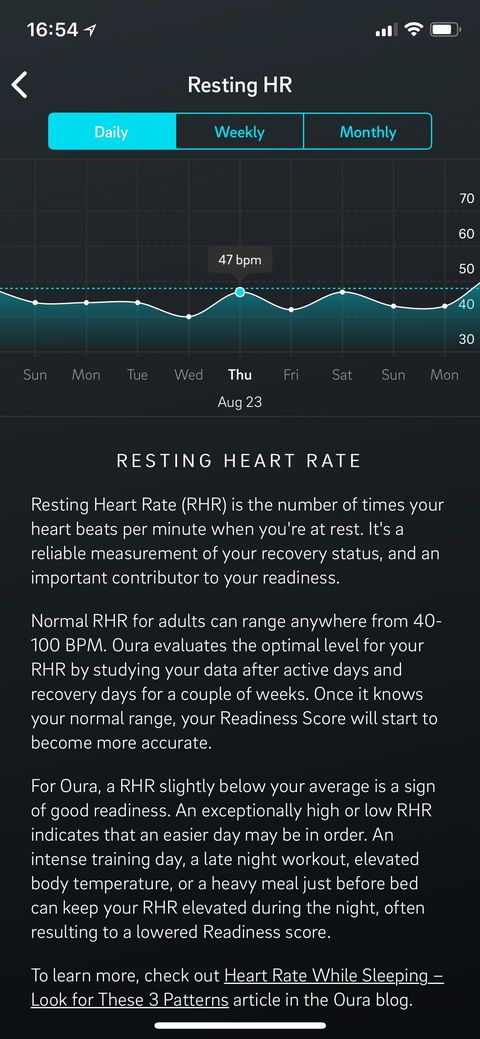

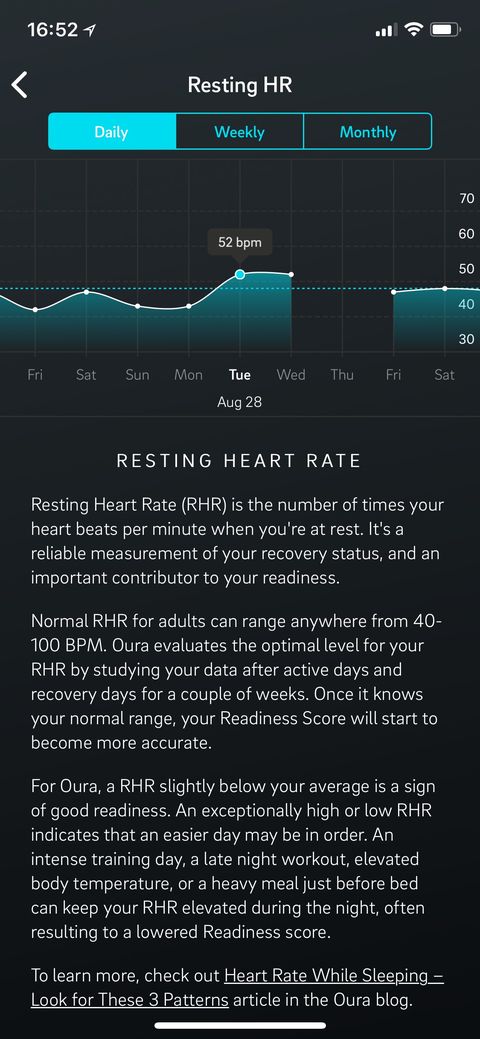

Woo also uses wearables to track his sleep. He’s a fan of the Oura ring monitoring device, which relays data like heart rate variability, resting heart rate, body temperature and how long is spent in REM, deep or light stages of sleep. Woo believes more time in between heartbeats and a lower resting heart rate are good indicators that his body is recovering better from daily stressors, like working out or digesting food, which presumably leads to better sleep quality.

At $999 for a silver diamond ring, the Oura is expensive. But wearable sleep and fitness like the Oura are rapidly moving out of the realm of Silicon Valley CEOs into the mainstream, with the wearables market estimated to be worth about $25 billion by 2019. It’s not hard to envision a future in which many, if not most, of us will have the data that Woo has at his fingertips, effectively making us all biohackers in one form or another.

Like most things that take root among a handful of people in Silicon Valley, biohacking has spread to Reddit, where people crowdsource tips to improve the quality of their sleep or reduce the need for sleep altogether. In the latter category are those attempting to become members of the “sleepless elite,” a term used to describe people who can sleep only a few hours each night without feeling cranky or fatigued.

In 2009, geneticist Ying-Hui Fu at the University of California San Francisco set out to determine why a small handful people don’t seem to experience the effects of sleep deprivation, even if they don’t get much rest. She found these people had a mutation on the hDEC2 gene, which may explain why they were able to survive on less sleep. Researchers believe the number of people genetically programmed to need less sleep is small — approximately 1% to 3% of the population — but that hasn’t stopped people from attempting to condition themselves to be like them.

These attempts are most likely futile, according to Jamie Zeitzer, associate professor at Stanford University’s Center for Sleep Sciences and Medicine. In fact, they may be dangerous: long-term sleep deprivation can result in a lowered immune system and increase your risk of injury from accidents.

Zeitzer says that while he is unaware of the magnetic pads Asprey uses, he is familiar with transcranial electrical stimulation. But he says that there is little evidence to indicate that it can induce or enhance stage-3 sleep. “They’re not getting more delta sleep. They’re just getting more delta wave activity during sleep,” he says, adding that more delta wave activity does not necessarily provide the benefits of deep sleep.

Zeitzer is also skeptical of sleep-tracking monitors, saying that even the best ones are insufficient measures of sleep quality. “The best they can do is [determine whether you’re] awake, in non-REM sleep, or in REM sleep,” he says. (REM sleep, or rapid eye movement sleep, occurs several times per night and is the stage when dreaming occurs.)

That said, there is sound research to back up much of what biohackers like Asprey and Woo do, says Dr. Vikas Jain, a sleep medicine physician at Northwestern University. For example, Asprey sets the temperature in his house to 68 degrees Fahrenheit, which is widely considered in the range of the optimal temperature for sleep.

Jain also says that Woo’s use of curtains and a white noise machine are also practical methods of ensuring good sleep hygiene. The light-blocking curtains in particular help synchronize our circadian rhythms, as our bodies naturally want to sleep when it’s darkest and stay awake when it’s light outside.

Both Jain and Zeitzer say there’s nothing wrong with people tracking and trying to improve their sleep. “I think it’s a good thing to look at the things that you do to help you feel better and perform better,” Jain told MensHealth.com. But they both say that any positive effects may be attributed to the placebo effect, which could be dangerous in the long run: if you think something works, “you can get used to the signals of sleep deprivation and start to ignore them,” says Zeitzer.

Zeitzer also cautions against people trying more extreme measures, such as electrical stimulation, where long-term side effects are often unknown. “A lot of what biohackers do to themselves, my institutional review board would not let me do to them,” he says.

Ultimately, Jain says, there’s a lot we don’t know about the science of sleep, so it’s unclear if biohackers will crack the code for a perfect night’s rest anytime soon. For now, he recommends trying three simple strategies: getting at least seven hours of sleep each night, limiting light exposure, and turning off all electronic devices at least one hour before bed.

Beyond that, it’s best to leave the experiments to the millionaires.

Source: Read Full Article