Before I talk about anyone’s drinking, you should know some things about me: I loved beer, too. Beer and bourbon and red wine and tequila neat and martinis that were so dirty with olive juice they were like slurping down the ocean. Sometimes, though, I forgot parts of an evening. It might be a sliver of a memory, a minute here or there, or it might be an hours-long swath of time. I tried to ignore these missing pieces. If I didn’t remember a thing, hey, maybe it didn’t happen.

It took a long time to understand the damage of my blackouts. It took a long time to understand blackouts, period, because most of us don’t. I’ve found a surprising number of people think blackouts are the same as passing out, but those two activities are quite different. A passed-out person is unconscious, while a person in a blackout may be conscious, but the next day they will have no memory of events. A blackout is a temporary memory loss likely brought on when the hippocampus stops placing information into long-term storage; it’s the brain’s version of “failure to send.”

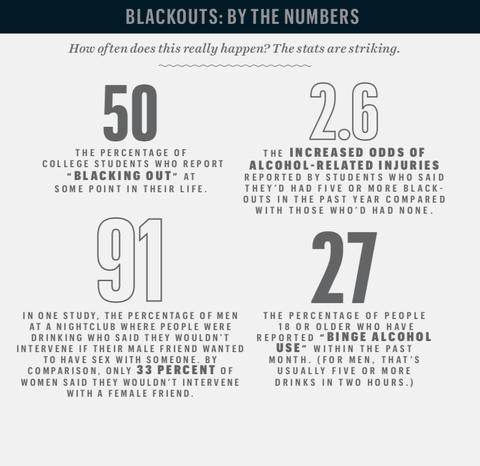

Not everyone has blackouts. The link may be genetic, but environment plays a part, too. Blackouts are rife in binge-drinking circles, because they’re caused by a rapid rise of alcohol in the blood, so it’s not just how much you drink that matters but, among other things, how fast. College provides an ideal landscape for blackouts. Shot contests, beer bongs, all those cutesy-clever games designed to force otherwise diligent students to chug mystery punch from red Solo cups. Drinking on an empty stomach can bump up blood-alcohol content and lead to blackout; drinking before going out to drink more, pregaming, is a good example. Social drinkers experience blackouts more than people once thought, and a landmark 2002 Duke University survey of college students found that about half of them had a blackout at some point in their life. Subsequent studies have backed up its findings. (Yes, it wasn’t even until this century that the medical industry began to see how pervasive blackouts are, even though drinkers themselves were familiar.) College kids have made a morning-after ritual out of scrolling through their camera rolls and laughing about the antics their brains didn’t record. When I mentioned this at a dinner party recently, a skeptical friend called over her 20-year-old son to confirm. He blushed and told us the name of his last frat party: Blackout or Back Out.

Journal of American College Health

For decades, society hasn’t looked too hard at this excess. College kids drink; that’s what they do. One problem with such an attitude is that many of us hold on to those habits well past graduation. I left a trail of empties across my 20s and early 30s, as my social activities and friend circles became more dependent on the bar. I moved to New York, where I never had to worry about driving, and a guy I used to drink with called our blackouts “time travel.” That sounded nifty to me. We weren’t drinking to the point of our brains shutting down; no, no, we had a superpower.

That blackouts are both morally and medically dangerous and yet touted as a badge of honor is a strange paradox. Somewhere along the way, extreme drinking became a rite of passage, a marker of courage and badassery for some, a mask of coolness for nerds like me. Drinking eased my social anxiety, my nagging sense of never being smart or pretty or brave enough. But the blackouts ratcheted up the anxiety alcohol was meant to manage. What did I say last night? Does everyone hate me now? I finally cried uncle at 35, and in the years after I quit, I decided to write a memoir about my drinking. People wanted to talk about women and their blackouts—that sounded dangerous, maybe salaciously so—but they rarely asked about the men, even as the men showed up in my in-box to hauntingly recount the damage.

That blackouts are both morally and medically dangerous and yet touted as a badge of honor is a strange paradox.

Punching walls. Punching friends. Punching girlfriends. All questionable manner of verbal and sexual assault. DUIs, jail terms, divorces. I’ve heard it all, and I can promise you that none of them are like that awesome tiger scene in The Hangover. That 2009 buddy comedy has probably done more than any other movie to elevate the fantasy of oblivion drinking into hilarious hijinks. But in real life, the hangovers are not so fun. The terror of blackouts is that you don’t know what you’ve done. You become an unreliable narrator in your own life. But just because you don’t remember something doesn’t mean you aren’t responsible for it.

I realize nobody wants to talk criminal liability at the kegger. But we have emerged into a moment when failing to discuss the repercussions of men’s excessive drinking is not only a failure of decency; it’s dumb. Heavy drinking and blackouts are like a river raging underneath today’s headlines: campus sexual assault, fraternity deaths, the #MeToo movement, an epic tussle over a Supreme Court nominee, not to mention the less sensational but no less tragic number of personal injuries and alcohol-related deaths that happen literally every day.

And here’s the thing: You don’t have to drink to such excess. You don’t have to quit drinking, either. You can just drink differently. Skip the shot contests, drink water between cocktails, try limiting yourself to two or three drinks in a night, instead of ten or 12. (Can anyone imagine ordering 12 slices of cake?) Stop egging each other on toward oblivion. No more chugging, no more guzzling.

Our culture has lied to young men. We told them the more they drank, the more impressive they’d be, but take a look at the frat boys facing probation for their brother’s death, or the college students forced to answer for sexual violence they committed in a blackout, or the grown men whose reckless pasts have come up for revision. Excessive drinking will unravel a future much faster than it will ever build it. What’s impressive is the man who knows his limits. Who has learned to savor the moment, not disappear inside of it.

Sarah Hepola is the author of the best-selling memoir Blackout: Remembering the Things I Drank to Forget.

Source: Read Full Article