Bob Beamon says he has to remind himself that his phenomenal world record long jump in 1968 was not a dream as he relives one of the biggest moments in Olympic history. He spoke to Sky Sports News about dealing with racism, why his own protest in Mexico City was not punished, and why we are “back to square one” as athletes consider protesting in Tokyo.

Beamon describes the period leading up to the 1968 Games in Mexico City as a “bittersweet feeling.”

“This was because of going to school, being under the gun (under pressure) of preparing for the Olympic Games, and dealing with a lot of racism that occurred during that time.”

But he says he remained “focused on the big prize of making the Olympic team” with the hope of a gold medal.

Despite being “very confident” with his training, Beamon fouled with his first two jumps because he overstepped and almost failed to qualify for the final. He sought help from his friend, team-mate and rival Ralph Boston.

With his third jump and final chance to qualify, Boston told him to make sure he started his jump well before the board so the jump would be legal. Beamon did and qualified easily for the final the next day.

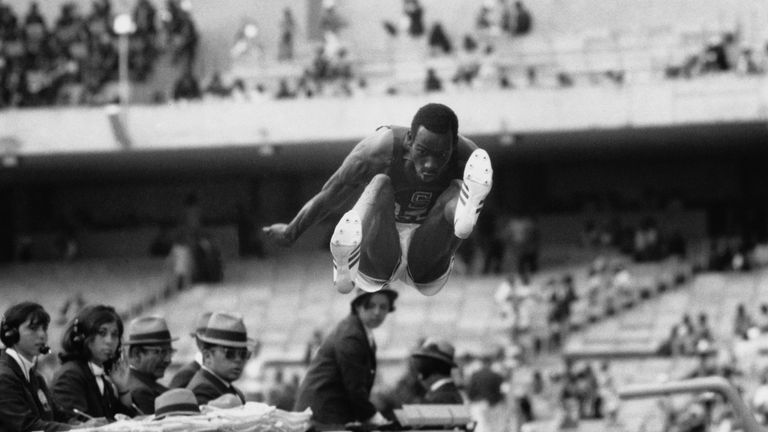

The incredible jump (18 October 1968)

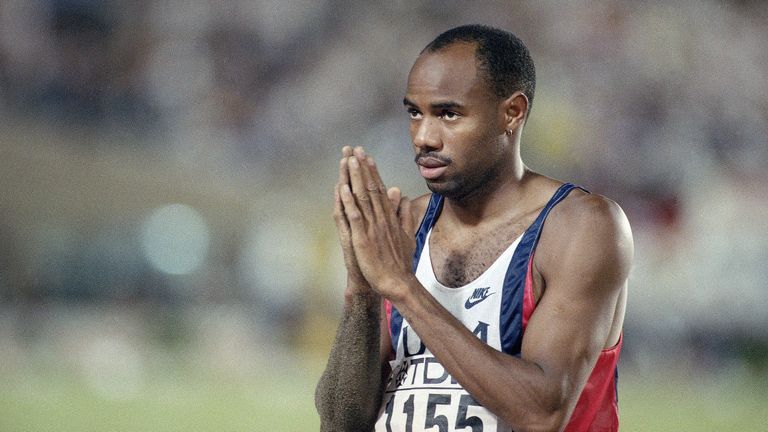

Beamon, only 22 at the time, was favourite to win gold at his first Olympics. He had won 22 out of 23 competitions that year.

His opening jump in the final changed the rest of his life.

He describes what happened as he smashed the world record and broke the Olympic record which still stands today.

“I was very confident everything was perfect. Life was perfect for me,” Beamon told Sky Sports News’ Gail Davis.

“Everything was pumping up and as I stood up at the head of the runway I couldn’t hear anybody speak or yell or anybody standing next to me.

“I could hear my heartbeat. And it was beating and so as I took off down the runway all I could hear was my heartbeat. I couldn’t even hear my feet pounding up against the rubberised track.

“And as I lifted off the board, I knew something was special because while I was in the air, I was looking at my watch,” Beamon laughs. Beamon loves to repeat the joke about the watch because those listening to the story enjoy hearing it.

But he admits he did not have a clear idea just how good his jump was.

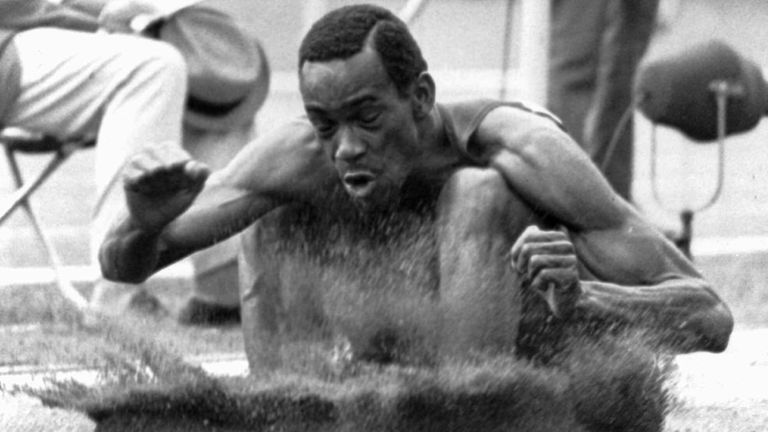

He said: “I landed and I didn’t land in the right way and I was rather upset about it, but what I noticed was that when I turned back a little bit and looked at the officials, they had the white flag up, which meant that I had a legal jump.

“And so I said: ‘oh well, what I will do is I’ll settle for this one but when I come back, I’m really going to take a real big one’.

“But what was happening was … the officials were trying to measure the jump on the electronic device, and the judge that was in charge of the electronic device kept telling the head judge ‘we can’t see it on the electronic scope’.”

At this stage, Beamon thought he could have broken the world record by a couple of inches and the officials were being careful. But this was not the case.

“The judge kept pointing to the devices, ‘there’s no there’s no indent in the sand here’,” the 74-year-old added.

“And so they had to go and find a manual tape to actually measure the jump because the electronic device only went up to about 28 feet and some change.”

‘I didn’t understand metres and centimetres!’

It took 20 minutes for the distance to be announced.

“And so they measured it at eight metres and 90cm and of course I didn’t even know what metres were! I only knew feet! And even today I have problems with centimetres,” said the 1968 Olympic champion.

With Beamon unfamiliar with the metric system, he turned to his friend Ralph Boston, who had helped to train Beamon and was a friend and rival for gold. Boston had won gold in the 1960 Olympics and silver in the 1964 Games.

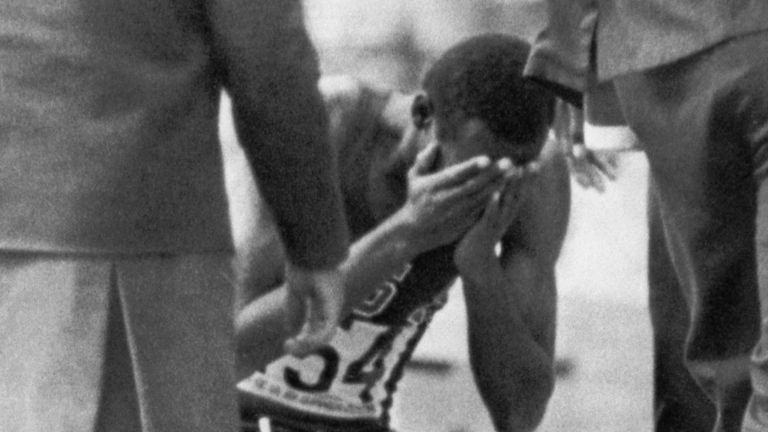

Beamon explains what happened next. “Ralph was very familiar with centimetres and all of that kind of good stuff – Ralph started calculating. He said ‘Bob, you just jumped over 29 feet.’ When he mentioned that we were actually walking and then all of a sudden I was on the ground.”

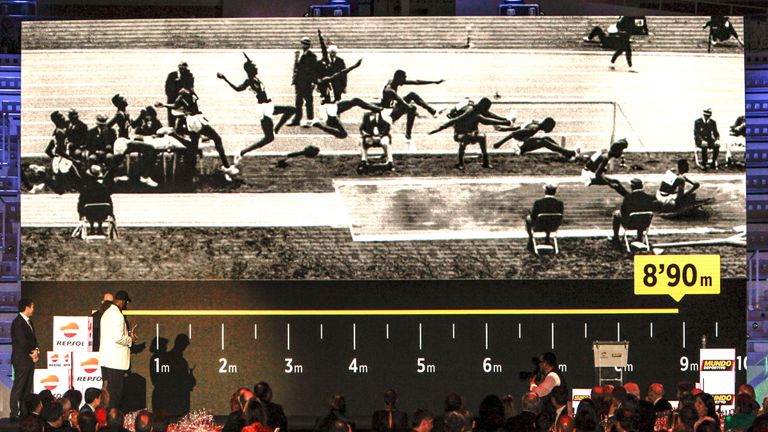

Beamon had jumped 29 feet and 2.5 inches, which smashed the previous world record by almost two feet (55cm). Nobody had jumped 29 feet before. And nobody had even jumped 28 feet before.

He said: “This was the part of the emotion. The feeling of ‘Oh my God, what are you talking about 29 feet?’ It was just an incredible moment for me. I think in a minute here, I’m going to wake up, and it was a nice dream. It was Oh God. Oh gosh, I’m having a wonderful dream. But it was for real.”

Beamon did jump again in the final but was nowhere near his opening jump. His rivals could not get close.

Bob Beamon. An Olympic champion who fulfilled his dream.

His phenomenal jump, sometimes referred to as “Leap of the Century”, was shown worldwide on television with tens of millions of Americans seeing it.

Many people have tried to explain why Beamon jumped so well that day. Many point to the tailwind and also the high altitude – which has been suggested is the reason many world records fell in Mexico City. But all the long jumpers experienced the same conditions that day.

Beamon says he had spent time working on his running speed with US sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos and he could run fast enough to make the US relay team.

“To be honest with you, I look back at it and I say, maybe it’s still a dream. Or sometimes you have to feel yourself and say, we’re in a real world,” he said.

His world record stood for 23 years until the World Athletics Championships in 1991 in Tokyo. American Mike Powell jumped 8.95m to set a new world record eclipsing Beamon’s jump by 5cm. Powell’s jump is the only time someone has jumped further than Beamon.

Beamon still holds the Olympic record and it is still the longest-standing record in a summer Olympics.

Losing my scholarship for boycotting

Growing up, Beamon had experienced racial injustice and division across the United States. This included the assassination of Dr Martin Luther King Jr. Just a few days after the death of the civil rights activist, Beamon and some athletes decided to make their own stand.

Beamon joined seven athletes to boycott a track meet at Brigham Young University because of their views and treatment of black African Americans. Beamon was at the University of Texas at El Paso at the time and was warned by the athletics director that he would lose his scholarship if he went ahead with the boycott.

Brigham was a Mormon school and the athletes were angry because they thought the institution promoted racial injustice.

Beamon told Sky Sports News: “There was not a good feeling or it was addressed as we were not as equal or were looked down upon as black people.”

But Beamon would not back down and with six months to go before the Olympics, he was suspended and his scholarship was taken away.

He had been “very sympathetic” to the views of many black athletes who wanted to boycott the Olympics that year over racial injustice. But Beamon also saw it as the first opportunity to achieve a dream.

“My gut reaction and my feeling was that I had trained from the time I was seven,” he said.

“I can’t say that I was training for the Olympic Games at seven, but that’s when I started to really feel like sports was something that was fun and something to do, and track and field became a part of it directly and indirectly.

“I kept my eye on the big prize and the big prize was to make the Olympic team.”

He feels it was vindicated as he won gold and also bravely protested on the podium after getting his medal.

Beamon protested but did anyone notice?

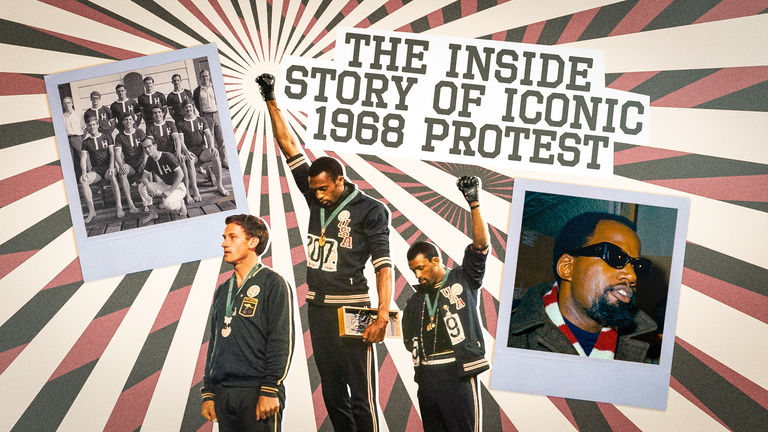

Two days before Beamon’s gold medal, John Carlos and Tommie Smith carried out their protest during the 200m medal ceremony.

Both men took off their shoes and wore black socks on the podium to highlight black poverty. Smith also had a black scarf to represent black pride, while Carlos had a necklace of beads to remember people who had been lynched.

They raised their fists in black gloves to show their support and solidarity with black people and racial injustice in the world. But they were punished by being suspended and were sent home.

Beamon got some advice from Boston on what he might do. Beamon said: “He [Boston] said with all of the negative publicity that John and Tommy got during the Olympics, he said that it would probably be appropriate that we use another form of protest that we feel would be the right thing to do.

When Beamon stood on top of the podium, he raised his right arm to show his fist but without the black glove famously used by Carlos and Smith. He also rolled up his tracksuit pants to show black socks in solidarity with the pair.

“I felt very comfortable with that protest of how African Americans were treated in the United States at the time,” Beamon added.

Beamon was not suspended or punished like Carlos and Smith. Why did his protest not get as much attention?

He says: “It’s kind of hard to say because it depends on how a reporter or IOC official has best described what he or she was watching during the time when they were playing The Star-Spangled Banner for the first-place winners.

“I felt that what we did were protests, but there shouldn’t be any blowback or any kind of negativism from what we were doing.”

‘Beamon’s story has not been elevated’

Professor Akilah Carter-Francique is an associate professor in the Department of African American Studies at San Jose State University.

She says the impact of the protest by Tommie Smith and John Carlos was a factor in reducing the impact of what Beamon achieved in 1968.

“As much as it was a phenomenal moment, an iconic moment and an opportunity for Tommie Smith and John Carlos to stand up and speak up about the marginalisation and the disenfranchisement of Black Americans in the US; it was also the first time that the Olympic Games was broadcasted live,” Carter-Francique said.

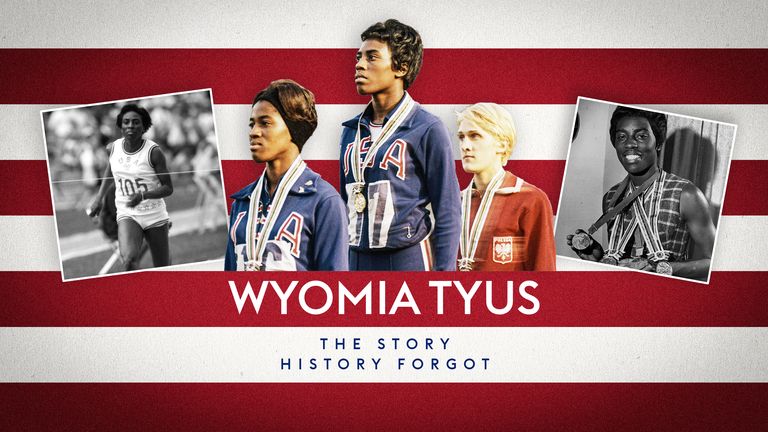

“So it took over the airwaves, it was uncensored. But within that, we found that great accomplishments like Wyomia Tyus [the first back-to-back Olympic 100m champion] and what she’s accomplished, and Bob Beamon there at the time got lost in that moment.

“And so those histories are there. They’re written, they’re documented, but they have not been elevated to the level that they deserve because of that moment and because of what happened in that significance.”

‘We’re back to square one on protesting’

Although the rules on protesting at the Olympics have been relaxed slightly, there is still a ban on protests during competition or medal ceremonies and at the opening and closing ceremonies of the Games in Tokyo.

Speaking before these rule changes were understood, Beamon says: “As much as we have moved forward, we’re almost back where we started some 50 years back.

“Because there are athletes that have said that they would make a protest. And this time, it’s not just black athletes, but it’s all types of athletes from all over the world, so this is not a one country kind of situation.”

Beamon feels progress has been slow as he watches Olympic athletes talk about a potential protest or sees LeBron James or Colin Kaepernick using their platforms.

“When they make those kinds of statements, when they make comments or when they talk about it, you see that we’re basically at square one again,” he said.

“After 50 years, you mean to tell me that young great athletes are now talking about what we talked about back in 1968. It’s a sad story … we’ve taken some steps forward, but we’ve taken five steps back.”

After the 1968 Games, Beamon carried on with the long jump sporadically but could not get close to his record in Mexico City. He was defined by that one jump by the public and felt the pressure to repeat the success.

After losing his scholarship, he went on to graduate with a degree in sociology from Adelphi University in 1972. In the same year, he had retired from track and field to end with one gold medal from one Olympics.

In 1983 he became one of the first athletes to be inducted into the US Olympic and Paralympic Hall of Fame. (His record jump is available to watch on the Olympics YouTube channel below).

https://youtube.com/watch?v=OnbIJcxLKgE%3Ffeature%3Doembed

What does ‘Beamonesque’ mean?

Beamon’s feat in that Games is still remembered today and is the longest-standing Olympic record. Sports Illustrated magazine put the achievement in their five greatest sports moments of the 20th century.

It also led to the word “Beamonesque” which the Olympics website described as “an athletic feat so superior to what has come before, it is overwhelming.”

He says he tries to watch the Olympics when he can but is still busy working in his 70s with business and other interests. He spends time to increase the opportunities of young kids so they have a better future than his tough upbringing in Queens in New York.

He has also worked as an ambassador for the Special Olympics and tells Sky Sports News he wants to remain involved in the Olympic movement.

What does he make of today’s track and field athletes? He says: “I say these guys are really unbelievable. I mean, they are just super, super, super-duper track and field athletes.”

Beamon never tires talking about the jump that made him an Olympics icon. He recounts the story weekly and sometimes daily.

He said: “That day in 1960, October 18, I can say that it was a peak experience in my life.”

Source: Read Full Article