The Skripals were ‘frozen like statues’: Britain’s top chemical weapons expert provides a gripping account of the Salisbury attack and how he became a target for Russian goons as Putin is accused of poisoning ANOTHER foe

As Putin is accused of poisoning ANOTHER enemy, a gripping inside account by Britain’s top chemical weapons expert of the day of the Salisbury attack – and how he ended up as a target for Russian goons

I took my phone out of my pocket and quickly gave it a glance. There were 52 missed calls and 108 WhatsApp messages. This was unusual. Something was clearly up.

Quickly finding a quiet corner after having come off a stage in Abu Dhabi where I had been delivering a keynote address at a security conference that day in March 2018, I noticed that, most worryingly, one of the missed calls was from a number I knew to be from friends in the intelligence world.

Ensuring that I couldn’t be heard, I dialled the number, only to swiftly be greeted by some choice Anglo-Saxon: ‘Where the hell are you?’

‘I’m in Abu Dhabi,’ I replied, bemused.

‘We have a situation.’

I instantly assumed this must be an issue in the Middle East, most likely Syria, where I had been doing a lot of work.

What came next stunned me.

‘We think there has been a chemical attack in Salisbury.’

The words chilled me to my core. I lived just outside Salisbury, with my wife Julia and our two children.

‘We think there has been a chemical attack in Salisbury.’ The words chilled me to my core, I lived just outside Salisbury, with my wife Julia and our two children

I only became more concerned as my friend outlined the situation.

‘Two Russians are in a serious condition. The doctors have never seen anything like it. They’re frozen, like statues.’

During my time as commander of the Army’s Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) Regiment, as well as Nato’s Combined Joint Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Defence Task Force, I had worked in war zones all over the globe, experiencing all the horrors that working in such a field can throw at you.

I’d stood on the edge of mass graves in Iraq, watched in horror as children gasped their last breaths in Syria, been chased through Afghan streets while carrying a huge fertiliser bomb, joined the Kurds in facing off against Islamic State, and risked my life trying to smuggle chemical samples across borders.

Yet following those inauspicious beginnings in the Gulf, it seemed my post-Army career had now come full circle, as my home town of Salisbury, my supposed safe haven, had been hit.

There was to be no escape. It seemed the spectre of chemical weapons had been following me all my life, no matter how hard I tried to avoid them.

News was still coming out in dribs and drabs but as my contact told me the details, it already sounded extremely serious.

‘The two victims are currently at Salisbury District Hospital,’ he said. ‘The doctor said they had to inject one of them with atropine over 30 times!’

‘Christ…’ I muttered. It would usually take a maximum of three atropine shots – a drug used to treat someone subjected to a nerve agent. Thirty was virtually unheard of.

‘Do they know what agent was used?’ I asked. ‘The doctor who treated them has worked on Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear with the Territorials,’ my contact replied.

‘He said it was unlike anything he had ever seen before.’What were the symptoms?’

‘They were found frothing at the mouth on a park bench, then they froze, almost like statues.’

‘It sounds like a nerve agent,’ I replied. ‘Maybe sarin.’

Yet even as I said this, I was aware that if 30 atropine shots had been used, it must have been either an extremely heavy dose of sarin or something far, far worse.

It would soon emerge that the two victims were Sergei Skripal, a former officer from Russia’s GRU intelligence directorate, and who had been a double agent in the 1990s before being arrested in Moscow in 2004, and his daughter Yulia.

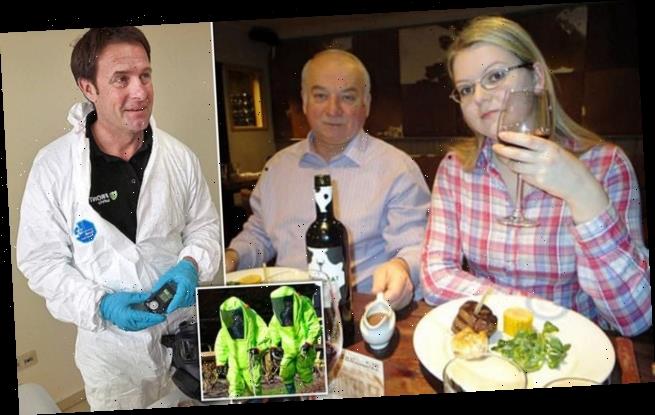

The Salisbury attack victims were Sergei Skripal (right), a former officer from Russia’s GRU intelligence directorate who was a double agent in the 1990s, and his daughter Yulia (left)

‘So we’re thinking Russian agents are behind this?’ I asked.

‘Definitely,’ my contact replied. ‘We are looking into the identities and whereabouts of all known agents and any Russians who have recently entered the country.’

As he spoke, fragments of the puzzle started to come together in my mind.

I thought this clearly sounded like another state-sponsored Russian hit job, in which a nerve agent had evidently been used. However, it sounded far more serious than anything we had ever seen before, far more potent. ‘It could be novichok,’ I blurted out.

‘What?’

I couldn’t blame him for not having a clue what I was on about, such was the mystery and secrecy surrounding one of the world’s most deadly agents.

I didn’t have time to explain all of this to my contact, as another terrible thought suddenly struck me. ‘The Skripals, where had they been before they were found?’ I asked.

I held liquid that could kill a million

Chemical weapons are the most vile weapons man has ever inflicted upon himself. They are undoubtedly extremely deadly, and they kill people in the most horrific ways possible.

I got a sense of just how powerful they were during training as commander of the Army’s Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) Regiment. On one occasion in a laboratory, I was manipulating a mixture that was the viscosity and colour of light honey. It didn’t look dangerous at all, and I felt quite confident as I stirred it with a glass rod.

‘In your hands you are holding the nerve agent VX,’ a scientist told us. ‘It is 50,000 times more potent than chlorine and many times more potent than sarin.’

I knew a bit about sarin, a deadly nerve agent developed by the Germans in the 1930s. But ever the smart aleck, I asked the scientist how deadly were the few centimetres I held in my hand.

‘If you were to correctly distribute what you are holding,’ he warned, ‘you could kill one million people.’

I quickly put the mixture down, my hands shaking. How could such a small amount of mixture kill so many people? It made the mind boggle and I realised why dictators such as Saddam Hussein craved such weapons.

No wonder that one lecturer had once used a phrase I will never forget: ‘As you can see, these are morbidly brilliant weapons.’

‘Brilliant’ was hardly the word that came to mind, but he was right.

From gas there is no escape. It can be released from out of harm’s way, spreading like an invisible secret agent, slipping into nooks and crannies, maiming and murdering anyone in its path, even if they try to hide.

As effective weapons, they certainly are ‘brilliant’, but they’re also downright evil. They kill indiscriminately, suffocating non-combatants who have no protection or even any warning that they are under attack.

‘All we know at this stage is that they had been at Sergei’s home in Salisbury, then the Italian restaurant Zizzi, before they were found by members of the public in the Maltings area.’

This was extremely concerning. If it was novichok, or even any other nerve agent, anything that the Skripals touched could be contaminated, not to mention the members of the public who found them, as well as the paramedics who initially treated them.

‘You need to close off everywhere you know they’ve been and decontaminate those areas quickly,’ I urged.

But it was already too late for some.

I later found that two of the police officers who had attended the Skripals’ house soon after the attack required treatment for itchy eyes and wheezing, while one, Detective Sergeant Nick Bailey, was in a serious condition in hospital.

As it dawned on us how serious this incident could be, I cut the phone call short to speak to my wife Julia.

‘Julia, don’t leave the house!’ I breathlessly shouted as soon as she answered.

‘What are you talking about?’

‘Where are the children?’ I asked, with no time to explain.

‘Jemima is getting ready to go out and Felix is in the cinema in town.’

‘Call him immediately, tell him to come home and tell him for Christ’s sake don’t touch anything.’

‘Hamish, what on earth is the matter with you?’

It was only as I outlined the severity of the situation that Julia hung up and ensured that she and the children remained safe at home. Until the emergency teams had decontaminated the area, and had tracked all of the Skripals’ movements, going into Salisbury was just too risky.

Large parts of the country now know exactly how this feels following the outbreak of Covid-19, but coming into contact with novichok would have been far more serious.

Arriving home, I found it all very strange. Usually, Salisbury was my sanctuary, a place where I could relax without the fear of chemical weapons. Now it was right at the heart of a major attack and it took a while to get my head around it.

I was curious to get a better look at where the Skripals had been found, in the Maltings area. I had to see the site of the attack itself to actually believe it had happened. As I drove there, I was amazed at just how deserted the streets were. I saw barely a soul.

Just as Britain has been on Covid-19 lockdown this year, Salisbury then was going through something very similar. It was clear that most people were terrified of this unknown, invisible enemy.

When I arrived at the Maltings, it looked like a scene from a war zone. Usually full of shoppers, the area was cordoned off, surrounded by police, while experts in hazmat suits collected further evidence. I was very surprised to see that the park bench where the Skripals had been found was still there.

Though everyone was wearing PPE, the bench must surely have been contaminated and presented a danger. But at least we knew the bench was contaminated. The big question was: what else had been?

I feared that traces of the agent must be all over the town, lying in wait, just like a virus. I also feared more might be out there. I shook my head at the thought.

The attack was so brazen, so reckless, that it almost defied belief. For more than an hour, I stood in the bitter chill, watching flecks of snow slowly cover up the scene, as if a crisp white layer might somehow mask and suffocate the evil that had been perpetrated.

Pictured, extremely lethal nerve agent VX stored in 1,269 steel containers at the Newport Chemical Depot in western Indiana in November 1997

With panic and wild conspiracy theories flying around, I tried to make myself available to answer any questions. However, it soon became apparent that I was being accused of spreading disinformation. The conspiracy theorists and ‘useful idiots’ were out in full force, as were Russian bots, who seized on any discrepancies to try to discredit the story that was now emerging.

A major Russian disinformation campaign was clearly under way, with Russian outlets posting at least 60 major pieces every day.

One of their favourite theories suggested that this was a ‘false flag’ attack to scapegoat the British authorities, and that the novichok that had been used had come from the UK Government military research centre nearby at Porton Down. This totally ignored the fact that the UK hadn’t manufactured nerve agents since the 1930s, apart from very small batches for research and testing. And this had certainly not been a small batch.

Such accusations were preposterous in any event. The UK had no motive for such an attack.

Yet as I sought to correct this story, the Russian-backed trolls soon turned their attention on me. They raced to tear through my private and professional life, eager to access any information that could be used against me, which thankfully was not a lot.

I did, however, start receiving threats in my direct messages, along the lines of ‘You’re next’, which alarmed me after what had just happened – and also considering that I was personally on Vladimir Putin’s radar.

For while working in Syria two years previously, the Russian President had warned my British doctor friend David Nott about my work trying to expose Syria’s use of chemical weapons.

After speaking with an intermediary of the Syrian leader, about trying to get Syria’s President Assad to call a ceasefire so that hundreds of injured children could leave the city of Aleppo, David received a call from a withheld number. It was Putin himself.

After David asked for a 24-hour ceasefire so that we could get the children out of the city on humanitarian grounds, Putin said ominously: ‘Tell your friend de Bretton-Gordon to stop accusing Assad of chemical attacks.’

But rather than back away, I decided that we needed to confront the Russians’ poisonous propaganda about what happened in Salisbury head-on.

I was curious to get a better look at where the Skripals had been found (above), in the Maltings area. I had to see the site of the attack itself to actually believe it had happened

Speaking to friends in the intelligence world, as well as some individuals I knew to be close to the Skripals, I was encouraged to do all that I could to counter the fake narrative.

I did the rounds on TV, spoke on the radio and did newspaper interviews, ensuring that the record was set straight and the various conspiracies were shown to be totally ridiculous.

To date, no one has been brought to justice for this appalling and reckless crime. Indeed, it has been alleged since that in recent years Russia might have killed 14 other so-called traitors on British soil.

The events in Salisbury were a real wake-up call for me.

For a good few years, I had found myself repeatedly smeared and threatened on social media, and, of course, Putin had warned David Nott about my work.

It appeared that the Russian state has no misgivings about targeting those they believe are enemies, so I have had to take steps to protect myself, my home and my family.

The threat is very real, not just to myself but to plenty of others, and I can’t but help think that the seeds for this were sown by the vote by British MPs in 2013 against taking action in Syria.

We were told at the time that a ‘red line’ had been crossed by President Assad, and that if action wasn’t taken, despots and terrorists would see chemical weapons as fair game. With no action taken, we have not only seen an explosion of chemical attacks across Syria and Iraq but we have now also witnessed attacks in the UK.

Indeed, in recent months the rules have been pushed to breaking point, with ever more chemical attacks being seen around the globe.

As a result, I still have a raging fire in my belly to make a difference, and just in the last few days I received a call from my good friend Dr Nott. ‘Hamish, I’m going to Syria. Do you want to come with me to train some of the staff on PPE and decontamination for Covid?’ At this, I looked at my wife. She was shaking her head, exasperated, but already knowing my answer. ‘Count me in,’ I replied, eager for the next challenge.

© DBG Defence Limited, 2020

Chemical Warrior, by Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, is published by Headline on September 3 at £20. Offer price £16 (20 per cent discount) until August 30. To pre-order, call 020 3308 9193 or go to mailshop.co.uk/books. Delivery charges may apply.

Source: Read Full Article