How long does coronavirus immunity REALLY last? 82-year-old man who recovered from the disease is struck down again just 10 days later with the SAME symptoms

- Sickly elderly man was taken into intensive care for four weeks and survived

- Just 10 days after being discharged from hospital he needed intensive care again

- Doctors and scientists can’t work out whether people can be infected twice

- Suggest the virus just lays dormant in the body before causing more symptoms

An 82-year-old man who spent four weeks in intensive care with Covid-19 was struck down by the virus again just 10 days after recovering.

The unidentified man went to an emergency department at Massachusetts General Hospital after suffering from a high fever for a week. He tested positive for Covid-19 and then his condition rapidly worsened while he was in hospital.

Doctors managed to save his life with a lengthy stay on a ventilator but he fell sick again less than a fortnight later, despite testing negative twice before being discharged.

The man’s case is one of many that raises questions about the type of immunity people build up against Covid-19, and how long it really takes to be cleared from the body.

Medics title their article ‘A case report of possible novel coronavirus 2019 reinfection’ and discussed how it was possible that the man recovered and tested negative but fell ill again.

Experts are still not sure whether people can catch the coronavirus twice and they are increasingly beginning to believe protection may only be short-lived.

Other coronaviruses that cause the common cold do not produce permanent immunity and people can catch them multiple times, and the same may be true of Covid-19.

Reports from around the world have claimed to see patients fall ill with the disease more than once, but there is little proof they are reinfections. A high profile group of cases in South Korea turned out to have been false positive results when patients were retested.

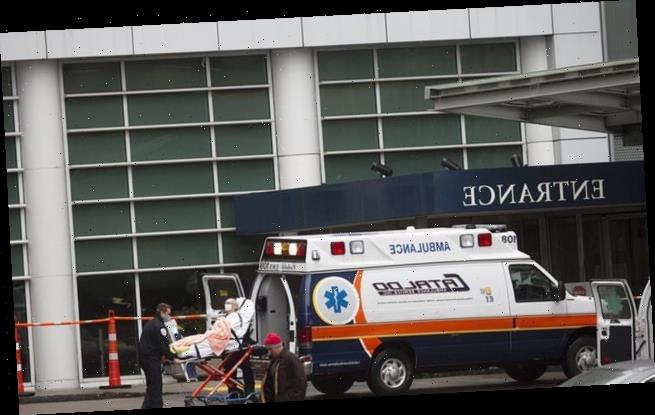

Doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital (pictured) revealed the case of the old man who, against all odds, managed to beat the virus twice despite ending up in intensive care both times (Stock image of the hospitals – the patient pictured is not the patient in the report)

The report, published in The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, detailed the case of the unnamed 82-year-old this month.

The man was already seriously ill before he caught coronavirus, suffering from Parkinson’s, diabetes, chronic kidney disease and high blood pressure.

All of these – and his old age – put him in the highest possible risk category of dying from Covid-19. But doctors managed to save him.

THE MYSTERY OF COVID-19 IMMUNITY

Scientists still do not know for sure whether people can catch Covid-19 more than once or if they become immune after their first infection.

With some illnesses such as chickenpox, the body can remember exactly how to destroy it and becomes able to fend it off before symptoms start if it gets back into the body.

But it is so far unclear if people who have had coronavirus can get it again.

Tests have shown that many people who recover have antibodies – which can produce future immunity – but it is not known whether there are enough of them.

One doctor, Professor Karol Sikora, said he had found that only 10 per cent of people known to have had Covid-19 actually developed antibodies.

This means it is hard to measure whether they could fight it off immediately if infected again.

Another study, by the University of Melbourne, found that all patients in a group of 41 developed antibodies but, on average, they were only able to fend off 14.1 per cent of viruses if they were exposed a second time.

Research into other similar coronaviruses, which also infect humans but usually only cause mild illnesses, found that people did tend to develop protective immunity but their antibody levels dropped off within months and they could get reinfected again after around six months.

However, antibodies are only one type of substance that can produce immunity.

Others, including white blood cells called T cells and B cells, can also help the body to fight off disease but are more difficult to discover using currently available tests.

The Melbourne study found signs of elevated numbers of coronavirus-specific B cells and T cells in recovered patients, suggesting those types of immunity may be stronger than antibodies.

They called for more research on the subject.

A promising study done on monkeys found that they were unable to catch Covid-19 a second time after recovering from it, which led scientists to believe the same may apply to humans.

The rhesus monkeys were deliberately reinfected by scientists in China to test how their bodies reacted.

Because the coronavirus has only been known to scientists for seven months there has not been enough time to study whether people develop long-term immunity.

But, so far, cases of people getting infected more than once have not been numerous nor convincing.

He appeared in the emergency department of the hospital complaining of a fever and shortness of breath for a week.

A chest X-ray and examination of his blood oxygen levels led doctors to believe he had Covid-19 and a swab test confirmed his diagnosis.

While in A&E the man’s lungs began to fail so he was put on a ventilator and rushed to intensive care, where he then spent 28 days recovering.

He spent a total of 39 days – five-and-a-half weeks – in hospital before being discharged to rehab.

After two negative coronavirus tests he was allowed to leave the ward and was breathing on his own.

But just 10 days later the man reappeared in the emergency department – again with a fever and struggling to breathe.

Another chest X-ray showed signs of Covid-19 infection in his lungs again, and a swab test again confirmed he was carrying the virus.

This time he and his family had asked doctors not to put him on a ventilator and not to resuscitate him if his heart stopped, but he was admitted to intensive care again.

In the ITU he went into shock and his kidneys failed – but again he survived, recovered and was sent back to a normal ward after a week.

After testing negative for coronavirus a further two times, he was discharged from the hospital for a second time after 15 days and is since believed to have recovered.

His medics said that, rather than getting infected twice, it’s likely he never fully recovered the first time and that tests weren’t sensitive enough to notice he was still carrying the virus.

The doctors, led by Dr Nicole Duggan, said: ‘Many viruses demonstrate prolonged presence of genetic material in a host even after clearance of the live virus and symptomatic resolution.

‘Thus, detection of genetic material by [swab test] alone does not necessarily correlate with the active infection or infectivity.

‘Observational data suggest SARS-CoV-2 viral shedding may last 20-22 days after symptom onset on average with some outlying cases exhibiting shedding as long as 44 days.’

They said that in one 71-year-old woman, a study had found she continued to test positive for Covid-19 five weeks after her symptoms disappeared.

Because the virus was only first discovered in December, scientists have not had the opportunity to work out how it affects people in the long-term.

In one study done by the University of Amsterdam, researchers suggested the coronavirus may act in the same way as other coronaviruses that cause common colds and other infections.

The researchers followed 10 volunteers for 35 years and tested them every month for four seasonal and weaker coronaviruses named NL63, 229E, OC43, and HKU1.

Those viruses are much more common and cause mild illnesses similar to the common cold.

They found those who had been infected with the strains — from the same family as SARS-CoV-2, the type that causes Covid-19 — had ‘an alarmingly short duration of protective immunity’.

Levels of antibodies, substances stored by the immune system to allow the body to fight off invaders in the future, dropped by 50 per cent after half a year and vanished completely after four years.

By studying how people recover from viruses from the same family as the one that causes Covid-19, the scientists say their research is the most comprehensive look at how immunity might work for the disease that emerged in China last year.

Writing in the study, which has not yet been published in a scientific journal or reviewed by other scientists, the scientists said: ‘The seasonal coronaviruses are the most representative virus group from which to conclude general coronavirus characteristics, particularly common denominators like dynamics of immunity and susceptibility to reinfection.

‘In conclusion, seasonal human coronaviruses have little in common, apart from causing common cold.

‘Still, they all seem to induce a short-lasting immunity with rapid loss of antibodies. This may well be a general denominator for human coronaviruses.’

PEOPLE PRODUCE ‘MODEST’ ANTIBODY RESPONSE TO COVID-19

Covid-19 survivors do not develop strong immunity against the coronavirus, a study has claimed.

With some illnesses such as chickenpox, the body can remember exactly how to destroy it and becomes able to fend it off before symptoms start if it gets back into the body.

But the coronavirus — called SARS-CoV-2 — did not seem to trigger this response in everyone who caught it, according to the research that deals a blow to hopes for widespread immunity without a vaccine.

A study of 41 people in Australia found that only three of them developed a strong enough antibody immune response that they could block half of the viruses if they got into the body again.

On average, the immune system’s antibodies were only able to block 14.1 per cent of the coronaviruses if someone was exposed to the illness a second time, making it likely that someone could get ill again.

Antibodies are only one type of immunity but they are usually the fastest-acting and what is needed to prevent illness.

Other types of immunity — such as that produced by white blood cells called T cells — may make disease less severe but not stop it completely. The Australian researchers said T cells appeared to be a better sign of immunity than antibodies.

The study was promising in that it showed coronavirus infection did stimulate the production of multiple types of immunity, including T cells and another form of white blood cell called B cells.

These could be ‘boosted’, one scientist suggested, if they weren’t produced in large enough quantities naturally.

The University of Melbourne researchers warned a vaccine is ‘urgently needed’ because having had Covid-19 once might not protect people from getting it again.

They added: ‘Our study also shows that herd immunity may be challenging due to rapid loss of protective immunity.

‘It was recently suggested that recovered individuals should receive a so-called “immunity passport”, which would allow them to relax social distancing measures and provide governments with data on herd immunity levels in the population.

‘However, as protective immunity may be lost by six months post infection, the prospect of reaching functional herd immunity by natural infection seems very unlikely.’

A study by the University of Melbourne discovered that antibody immunity – which many had pinned their hopes on – only seems to develop in ‘modest’ amounts in Covid-19 patients.

Tests on 41 people in Australia found that only three of them developed a strong enough antibody immune response that they could block half of the viruses if they got into the body again.

On average, the immune system’s antibodies were only able to block 14.1 per cent of the coronaviruses if someone was exposed to the illness a second time, making it likely that someone could get ill again.

Antibodies are only one type of immunity but they are usually the fastest-acting and what is needed to prevent illness.

Other types of immunity — such as that produced by white blood cells called T cells — may make disease less severe but not stop it completely. The Australian researchers said T cells appeared to be a better sign of immunity than antibodies.

The study was promising in that it showed coronavirus infection did stimulate the production of multiple types of immunity, including T cells and another form of white blood cell called B cells.

These could be ‘boosted’, one scientist suggested, if they weren’t produced in large enough quantities naturally.

The Australian researchers warned a vaccine is ‘urgently needed’ because having had Covid-19 once might not protect people from getting it again.

Other more promising research, however, has found that monkeys are unable to be reinfected with the virus in laboratory experiments.

Researchers in China infected rhesus monkeys with coronavirus, allowed them to recover, and then re-exposed them to the virus 28 days after the initial infection.

However, the monkeys were seen to have appeared to have developed protection against the infection and did not succumb a second time.

This, the team argued, would suggest that patients who appeared to become ‘reinfected’ with coronavirus merely had not fully overcome the initial infection.

MONKEYS CAN’T BE REINFECTED WITH CORONAVIRUS, IN A SIGN THAT IMMUNITY MIGHT WORK

Monkeys can’t be reinfected with coronavirus in a sign herd immunity could kick in, as scientists dismiss fears patients may ‘relapse’ after recovery from infection.

Researchers in China infected rhesus monkeys with coronavirus, allowed them to recover, and then re-exposed them to the virus 28 days after the initial infection.

However, the monkeys were seen to have appeared to have developed protection against the infection and did not succumb a second time.

This, the team argue, would suggest that patients in China who appeared to become ‘reinfected’ with coronavirus merely had not fully overcome the initial infection.

The findings also have the potential to help evaluate the development of a vaccine against COVID-19, the researchers said.

In their study, Linlin Bao of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and colleagues infected four adult Chinese rhesus monkeys with the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

The researchers observed the progression of the resulting disease for the next 28 days — monitoring the animals’ weight and temperature and taking various swabs to measure viral load.

During the course of the infection, the team observed the animals losing between 7–14 ounces (200–400 grams) of weight, alongside signs of reduced appetites, higher breathing rates and hunched postures.

Swabs also revealed that the monkey’s viral loads peaked at around three days after infection, after which they gradually decreased — reaching undetectable levels after around 14 days.

Twenty-eight days after infection, two of the monkeys — with both their symptoms having abated and having passing two successive coronavirus tests — were once again exposed to coronavirus, at the same dose as the previous infection.

While both monkey’s temperatures were seen to rise temporarily after re-exposure to, swabs taken revealed no viral load.

Source: Read Full Article