In 2013, a cataclysmic meteor the size of a six-story building broke apart above Chelyabinsk, Russia, and the resulting blast was stronger than a nuclear explosion. In 2068, astronomers believe a potentially hazardous “God of Chaos” asteroid could slam into Earth. Both events suggest humans—and every other animal and plant on Earth—are much more susceptible to total annihilation than we think.

That’s why scientists at the University of Arizona are proposing a far-out concept that just might save us all: a 21st-century version of Noah’s Ark … on the moon.

This ark wouldn’t contain two of every animal, but rather, a repository of cryogenically frozen reproductive cells from 6.7 million species on our planet.

Consider it a global insurance policy of sorts, says Jekan Thanga, Ph.D., the mastermind behind the project. Thanga is an assistant professor at the University of Arizona’s Department of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering, where he and a group of his undergraduate and graduate students have been toiling over this “lunar ark” concept for the past two years.

“As a human civilization, we’re in a fragile state,” Thanga tells Pop Mech. “We’re not really that rigid or able to face all kinds of adversities. And Earth’s ecosystem is also very fragile.”

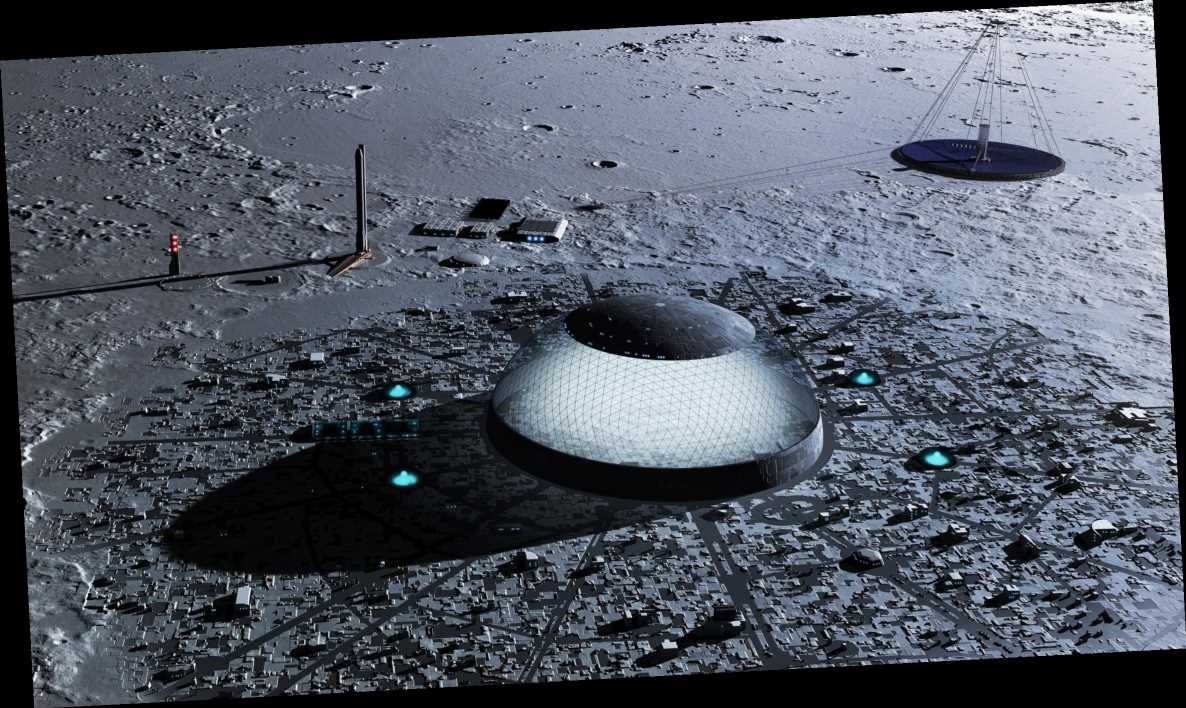

Enter the lunar ark, which would be a storage shelter filled to the brim with genetic material for the most important plants and animals on Earth.

From the network of lava tubes just beneath the moon’s surface where scientists hope to build the compound, to the lunar solar farm that generates electricity for the underground facility, to the robotic lab techs, the lunar ark sounds like the setting for a sci-fi novel. But Thanga says the possibility for such a shelter is very real—and it could come to fruition in the next few decades.

The Moon as a Storage Unit

While we Earthlings may eventually need to evacuate our planet if we’re right in the trajectory of a massive asteroid, a moon colony isn’t necessarily the best option, Thanga says.

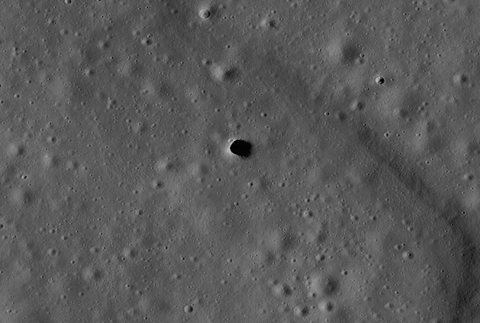

For the past seven years, his team has been studying the moon’s extensive network of over 200 lava tubes just beneath its rocky surface—the underground tunnels where a moon settlement would make the most sense.

These tunnels formed billions of years ago when streams of lava melted through the soft rock underground. While the lava tubes are about 328 feet in diameter and could provide a sanctuary from solar radiation, micrometeorites, and cruel surface temperatures, they aren’t a particularly homey space for people to live in and thrive.

“Setting up a base inside a lava tube seems like a plausible way to go if we wanted to set up a permanent settlement on the moon,” Thanga says, but these moon shafts may not be compatible with the human condition.

He puts it bluntly: “We as humans are not mole rats. We’re going to feel pretty stuffy being underground without being able to see outside.”

So what’s the next best use for a nearby celestial body with a stable environment that only takes about four days to reach on a supply mission? Turn it into a storage locker of sorts for the most precious data on Earth: our own reproductive cells.

Noah’s Ark 2.0

To build a lunar ark, you don’t necessarily need to reinvent the wheel; much of Thanga’s inspiration for the architecture includes the kinds of materials you might use to build a structure on the surface of the moon, so long as the parts would fit inside a lava tube.

Thanga and his colleagues have proposed sending miniature hopping and flying robots into the lunar lava tubes to collect samples of regolith, or loose rock and dirt. Then, researchers could examine those samples to learn about the layout, temperature, and makeup of the lava tubes, ultimately guiding design considerations for the base.

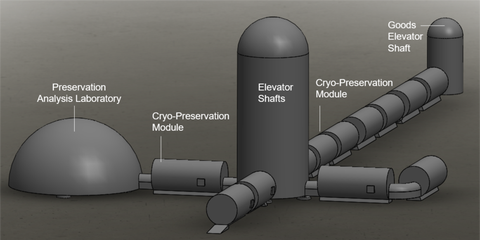

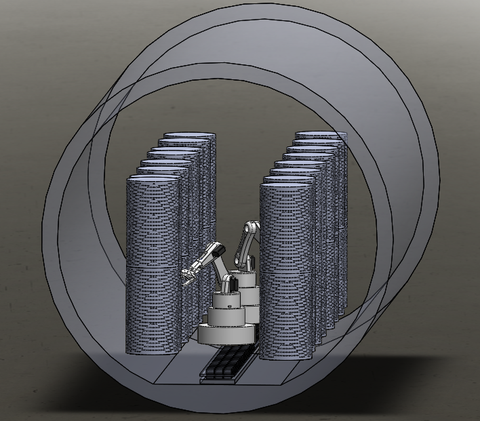

“What we envision is taking one of the existing pits—just the opening into the lava tube—and installing an elevator shaft there,” Thanga says. From there, the elevator shafts would function as the entry and exit to the cryo preservation modules below the lunar surface. Robots or astronauts would be able to use the elevators to check in and check out samples in petri dishes, “much like a library.”

The plans also include room for a second elevator shaft that robots or astronauts could use to transport construction material below the surface. That way, they could expand the base from inside the lava tubes.

To send messages back to Earth, we’ll need a parabolic antenna at the surface of the base. It would likely operate on the Kₐ band, says Thanga, which is the most modern portion of the electromagnetic spectrum used for data transmission.

“That system could directly get in touch with Earth in its line of sight,” he says. “Out of line of sight would need a relay satellite, which is possible, but the infrastructure isn’t there at the moment.”

For power, the lunar ark will use a set of solar panels—much like a solar farm on Earth—to turn sunlight into electricity. But depending on where the base is set up, the surface of the moon could go through cycles of 12 days of daytime and 12 days of darkness, Thanga says.

His design calls for modular batteries that will attach to the cryo preservation modules to keep the lights on and maintain the right temperatures for the samples.

Lunar Cryogenics

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway is a somewhat appropriate analog for the lunar ark. But storing 6.7 million gametes, spores, and seeds isn’t the same in space as it is on Earth; there are added challenges due to the microgravity on the moon and bitter cold temperatures.

To preserve the samples with cryopreservation techniques, human or robotic archivists must store the seeds at -292 degrees Fahrenheit, and the stem cells at -320 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s far cooler than the inside of the lava tubes, which usually remain stable at about -15 degrees Fahrenheit.

This means the cryogenic modules could jam or freeze together. To combat that risk, plus the relative lack of gravity, the facility could use a spinning apparatus—much like a cement truck—that uses centrifugal force to keep the modules in motion.

All the while, robots connected to a magnetic strip could remove the samples from their modules and transport them to an analysis lab, periodically checking to see if the seeds and sex cells are stable.

250 Launches, 30 Years, and 6.7 Million Species

If this all sounds a bit far-fetched, Thanga says the lunar ark could actually be possible in the next 30 years, especially as private companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin continue to drive down the cost of space launches.

With some back-of-the-envelope calculations, Thanga estimates it would take 250 rocket launches to carry 50 specimens each of the 6.7 million species his team wants to preserve on the lunar ark. To put that into context, it took 40 launches to build out the International Space Station.

And what happens when that devastating meteor inevitably strikes the Earth? Let’s just hope there’s someone left who knows how to get to the lunar ark and use those reproductive cells to create life.

🎥 Now Watch This:

Source: Read Full Article