SAN FRANCISCO — In George Orwell’s “1984,” the classics of literature are rewritten into Newspeak, a revision and reduction of the language meant to make bad thoughts literally unthinkable. “It’s a beautiful thing, the destruction of words,” one true believer exults.

Now some of the writer’s own words are getting reworked in Amazon’s vast virtual bookstore, a place where copyright laws hold remarkably little sway. Orwell’s reputation may be secure, but his sentences are not.

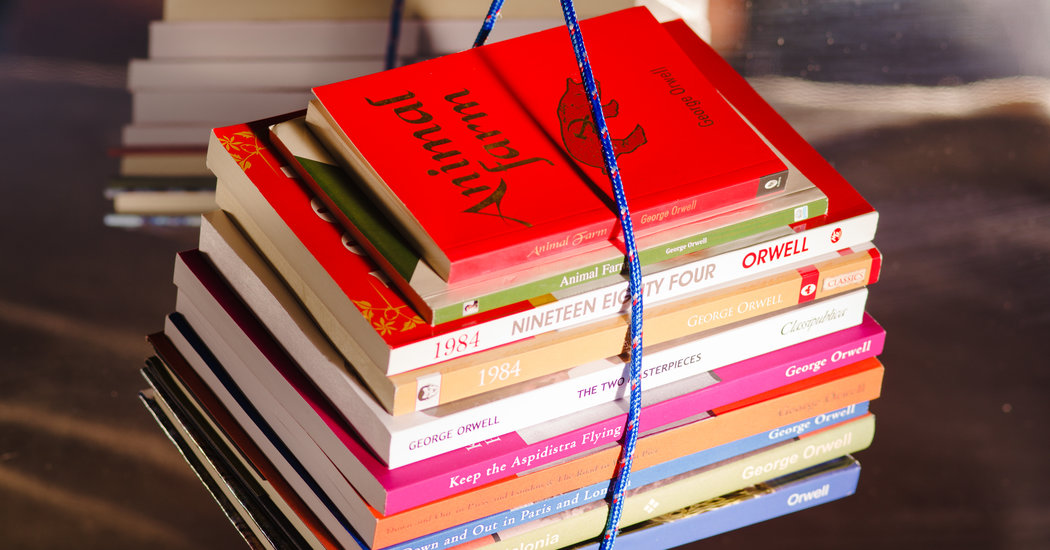

Over the last few weeks I got a close-up view of this process when I bought a dozen fake and illegitimate Orwell books from Amazon. Some of them were printed in India, where the writer is in the public domain, and sold to me in the United States, where he is under copyright.

Others were straightforward counterfeits, like the edition of his memoir “Down and Out in Paris and London” that was edited for high school students. The author’s estate said it did not give permission for the book, printed by Amazon’s self-publishing subsidiary. Some counterfeiters are going as far as to claim Orwell’s classics as their own property, copyrighting them with their own names.

What unites all these books is that none of them paid the author anything, which means they could compete with legal Orwell titles as a lower-cost alternative. After all, if you need a copy of “Animal Farm” or “1984” for school, you’re not going to think too much about who published it. Because all editions of “1984” are the same, right?

Not always, not on Amazon.

One reader discovered, to his surprise, that his new copy of “1984” had passages that were “worded slightly different.” Another offered photographic proof that her edition was near gibberish. A third said the word “faces” was replaced in his copy with “feces.” Getting Orwell books that skip a chunk of pages seemed to be a routine experience.

Even the titles changed. One edition of “Animal Farm: A Fairy Story” referred to itself on the back cover as “Animals Farm: A Fair Story.” The preface referred to another great Orwell work, “Homage to Catalonia,” as “Homepage to Catalonia.”

I started browsing Orwell on Amazon after writing about the explosion in counterfeit books offered by the retailer. The fake books appeared to help Amazon by, for example, encouraging publishers to advertise their genuine books on the site. The company responded in a blog post that it prohibits counterfeit products and has invested in personnel and technology tools including machine learning to protect customers from fraud and abuse.

On Sunday, Amazon said in a statement that “there is no single source of truth” for the copyright status of every book in every country, and so it relied on authors and publishers to police its site. “This is a complex issue for all retailers,” it said. The company added that machine learning and artificial intelligence were ineffective when there is no single source of truth from which the model can learn.

Bookselling is an ancient and complicated profession, and fake editions of all sorts can turn up anywhere. But Amazon is the world’s biggest bookstore and the standards it sets have ripples everywhere.

How it treats Orwell is especially revelatory because their relationship has been fraught. In 2009, Amazon wiped counterfeit copies of “1984” and “Animal Farm” from customers’ Kindles, creeping out some readers who realized their libraries were no longer under their control.

Orwell resurfaced in 2014 during Amazon’s bare-knuckles fight with the publisher Hachette over e-book sales. Amazon tried to use a quotation by the author — renowned for his moral rectitude — to suggest he was a sleaze in favor of illegal collusion. It turned out the quote was very much out of context.

My newly acquired Orwell shelf was frankly dismal — typos galore, flap copy lifted directly from Wikipedia, covers that screamed “amateur.” Eleven of the books were sold directly by Amazon as new books and were shipped from an Amazon warehouse; one was sold as a new book by a third party. Prices ranged from $3 to $23.

The counterfeits and imports are generally the least expensive editions, and who can blame people for buying those? So they do. A $7.99 legitimate edition of “1984” was recently ranked at No. 72 among all Amazon books. A $5 Indian import was at No. 970, which suggested copies were selling at a steady clip.

Most of the distorted texts are likely due to ignorance and sloppiness but at their most radical the books try to improve Orwell, as with the unauthorized “high school edition” of his 1933 memoir. The editing was credited to a Moira Propreat. She could not be reached for comment; in fact, her existence could not be verified.

“Down and Out” is an unflinching look at brutal behavior among starving people, which makes Ms. Propreat’s self-appointed task of rendering the book “more palatable” rather quixotic. An example of her handiwork came when Charlie, a boastful rapist, described how he lured a young woman into his clutches:

“‘Come here, my chicken,’ I called to her.”

Ms. Propreat’s version:

“‘Come here,’ I called to her.”

It’s unlikely that Orwell, a finicky master of English prose, would have appreciated this editing — nor the fact that all the French in the book is rendered in capital letters, which makes it seem like the writer is shouting at the reader.

Until recently, improving Orwell was not a practical business proposition. Then Amazon blew the doors off the heavily curated literary world. No longer was access to the marketplace determined by publishers, booksellers or reviewers. Even the most marginal books were suddenly available to everyone everywhere.

Breaking down the doors, however, also let in people who did not appear to care about the quality of what they sell.

“Once a week a counterfeit pops up,” said Bill Hamilton, the agent for the Orwell estate. “When will a company like Amazon take responsibility for the curation of the products passing through their hands?”

If Amazon vetted each title the way physical bookstores do, it would need lots more employees. That would cost more, dragging profits down. I searched my Amazon account for a way to tell the retailer it was selling me counterfeits and came up with nothing. (Amazon suggested I use the blue “report incorrect product information” button on every page, or give them a call. If I returned the book, I could select a reason from some drop-down options provided.)

The Authors Guild said that in the last two years, the number of piracy and counterfeiting issues referred to its legal department has increased tenfold. Counterfeit editions are a blow against the authority of the book and accelerate a dangerous trend toward misinformation.

“During most of human existence, facts have been hard to pin down and most of knowledge was oral history, rumor and received wisdom,” said Scott Brown, a prominent California bookseller. “We have spent our whole lives in a fact-based world and while that seems how things ought to be, it may prove to have been a temporary aberration.”

Mr. Brown noted that the news was now mostly digital. “Who can really say what an article really said when it was published? There’s rarely a printed — and therefore hard-to-change — version to refer back to,” he said. “The past is becoming unmoored and unreliable.”

One of the Orwell books I bought was a copy of “Animal Farm” issued by Grapevine India. On the copyright page it declared, “The author respects all individuals, organizations & communities, and there is no intention in this novel to hurt any individual, organization [or] community.”

Orwell said no such thing, his estate confirmed. This was a 2019 sentiment tacked onto a 1945 story. But then, in this edition of “Animal Farm,” the author and the past barely exist. There was no copyright acknowledgment, no mention of the year 1945.

In “Politics and the English Language,” Orwell wrote that “the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.” He would have found his point confirmed by another Indian edition of “Animal Farm” sold by Amazon, this one from Adarsh Books. One sentence in the introductory blurb goes like this: “When the animals, the so-called characters in the novel, are making their attempts to learn the alphabet in different ways, is definitely the scene that would be bringing some unexpected laughter to the reader.”

The Adarsh edition was seemingly created using an optical scanner, which often results in misspelled words. One well-known passage in “Animal Farm” tells how the seven commandments of the farm are written on the wall. No. 2 goes like this: “Whatever goes upon four legs, or has wings, is a friend.”

Adarsh’s version goes on to note that the spelling of the commandments is correct “except that ‘friend’ was written ‘friend.’” If you’re confused, it’s because that second “friend” is supposed to be “freind.” One of Orwell’s signature passages was thus rendered incomprehensible.

Grapevine and Adarsh are free to publish these books in India. But after I asked Amazon about the Indian editions last week, it removed them from sale in the United States, including a digital “1984.” It also removed the counterfeits I asked about. An email to Adarsh’s address as printed on its edition of “Animal Farm” bounced back. Grapevine did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Even assuming Amazon customers care, it is difficult for them to know they are getting a legitimate edition. Amazon sometimes bundles all the reviews of a title together, regardless of which edition they were written for. That means an unauthorized edition of “Animal Farm” can have thousands of positive reviews, signaling to a customer it is a valid edition.

At the other extreme, reviews that expose a counterfeit edition will remain even if the edition itself disappears. A reader complained — and provided photos as proof — that his copy of “Animal Farm” had the words “Chapter IV” inserted into the text anytime there was a word with the letters “iv.” For example: “He was unChapterIVersally respected.”

“A literary nightmare,” the reader concluded.

The large publishers, which have remained mostly mute since they were on the losing side of an antitrust clash with Amazon over e-reading, are now finding their voice again. Their trade group, the Association of American Publishers, just filed a heavily researched analysis with the Federal Trade Commission that is remarkably blunt.

“The marketplace of ideas is now at risk for serious if not irreparable damage because of the unprecedented dominance of a very small number of technology platforms,” the report concluded.

Meanwhile, the books are mutating. A reader recently tried to sound the alarm about a different dystopian classic he bought on Amazon.

“This is not the real Fahrenheit 451,” he wrote. “The wording is different, the first chapter is not properly titled, they used the first sentence of the chapter as the title in this book. There are typo’s and spacing issues. They need to advertise that this is not an authentic book.”

David Streitfeld has written about technology and its effects for twenty years. In 2013, he was part of a team that won a Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting.

Source: Read Full Article