Just like you, our planet has a ticker that keeps time: Earth’s geological “heartbeat” goes off on a regular schedule, albeit with millions of years in between, says a new study in Geoscience Frontiers.

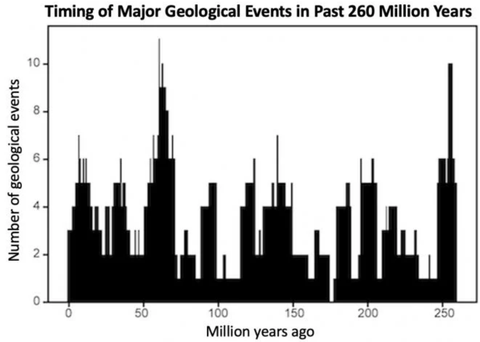

When scientists from New York University and the Carnegie Institution of Science in Washington D.C. analyzed 260 million years of geological feedback, they found “global geologic events are generally correlated,” and seemingly come in pulses every 27.5 million years.

Those events include everything from “times of marine and non-marine extinctions, major ocean-anoxic events, continental flood-basalt eruptions, sea-level fluctuations, global pulses of intraplate magmatism, and times of changes in seafloor-spreading rates and plate reorganizations,” the authors write. They considered a total of 89 such major events from the last 260 million years, from which the 27.5 million-year cycle emerged.

Scientists have long suspected a somewhat cyclical nature to events like these, dating back to at least the 1920s. But to really understand what’s happening, we must “extract potential signals from the noise” using statistical techniques, the study authors say. The right statistical analysis looks at a cloud of questionably related events and pulls likelihoods of certain outcomes based on the data points.

Something else had to fall into place, too. That’s the specificity and accuracy of carbon-dating techniques that are used to pair our knowledge of events with the true timeframe of when those events occurred.

Lead study author Michael Rampino, a geologist who teaches in the biology department at NYU, has been studying these periodic events since at least 1984. Back then, scientists believed the interval was more like 33 million years, and estimates for different kinds of events in research range from 26 to 36 million years apart.

How do these events end up clustering together around this newly emerged 27.5 million-year cycle? There’s probably some causal relationships between, say, volcanism that causes both seafloor spread changes and ocean anoxia, which is when the oxygen level falls precipitously and lead to extinctions. Everything ends up tied together when it comes to ecosystems and the planetary balance.

“We note that 7 out of the 12 marine-extinction events and 6 out of the 9 non-marine tetrapod extinction episodes in the last 260 [million years] are significantly correlated with the pulses of continental flood-basalt volcanism,” the scientists explain. So, the extinctions appear to be at least partly caused by the volcanism. “The potential cause-and-effect relationships between the geologic activity and biotic changes may be complex, but there are several apparent causal chains.”

Statistical analysis helped the scientists group 89 total “well-dated” global geological events into clusters that pop up with regularity roughly every 27.5 million years. “Whatever the origins of these cyclical episodes, our findings support the case for a largely periodic, coordinated, and intermittently catastrophic geologic record, which is a departure from the views held by many geologists,” Rampino said in a statement.

🎥 Now Watch This:

Source: Read Full Article