A controversial Chinese genetic experiment may have resulted in the creation of two babies with mutated genes, scientists have warned.

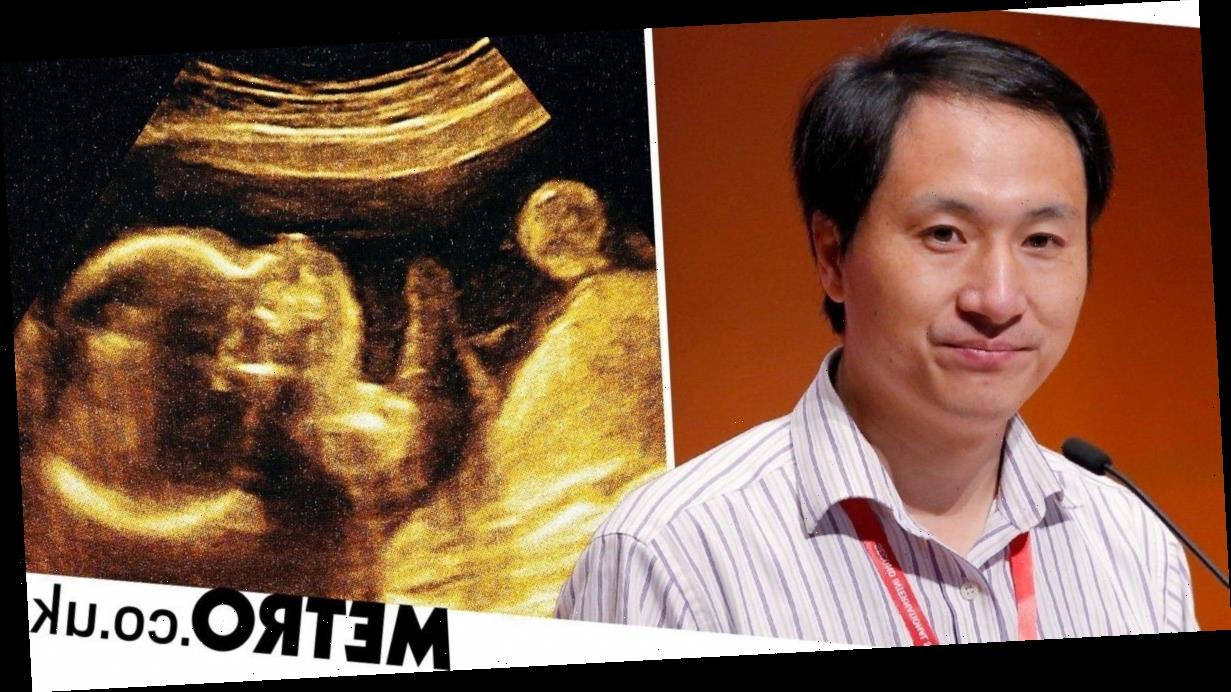

Last year, biophysicist He Jiankui edited the DNA of twin girls called Lulu and Nana in a bid to make them immune to HIV.

But scientists have now claimed the process may have failed and created mutations with effects could be impossible to predict.

A particular gene called CCR5 was removed from their genetic code before birth. Getting rid of this gene has been shown to make mice smarter and may have an effect on the girls’ cognitive abilities.

Excerpts from a manuscript describing the research have now been released by the MIT Technology Review.

Fyodor Urnov, a genome-editing scientist at the University of California, Berkeley said: ‘The claim they have reproduced the prevalent CCR5 variant is a blatant misrepresentation of the actual data and can only be described by one term: a deliberate falsehood.’

‘The study shows that the research team instead failed to reproduce the prevalent CCR5 variant.”

The Chinese scientist attempted to get his manuscript published to prestigious journals including Nature and JAMA, but they have not yet taken him up on the offer.

Earlier this year, scientists said it was probable that the girls would grow up with different brain powers than they would have done without genetic editing.

They were born to a father with HIV.

‘The answer is likely yes, it did affect their brains,’ Alcino J. Silva, a neurobiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, told the MIT Technology Review.

‘The simplest interpretation is that those mutations will probably have an impact on cognitive function in the twins,’ said Silva, whose lab uncovered a major new role for the CCR5 gene in memory and the brain’s ability to form new connections.

The HIV virus requires the CCR5 gene in order to enter human blood cells.

But one of the reasons this kind of editing shouldn’t be carried out, Silva argues, is because of the uncertainty over how this will affect the girls’ brains over time.

It’s unclear whether or not He Jiankui, who led the CRISPR experiment last year intended to try and affect the intelligence of the babies. He, from the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen (which denied knowing about the work) defended the experiment despite condemnation from the wider scientific community.

Nobel laureate David Baltimore said professor He’s work would ‘be considered irresponsible’ because it did not meet criteria many scientists agreed on several years ago before gene editing could be considered.

Baltimore said he didn’t think that was medically necessary. He said the case showed ‘there has been a failure of self-regulation by the scientific community’ and said the conference committee would meet and issue a statement on Thursday about the future of the field.

The National Health Commission has ordered local officials in Guangdong province to investigate He’s actions, and his employer, Southern University of Science and Technology, is investigating as well.

The Chinese researcher said he practiced editing mice, monkey and human embryos in the lab for several years and has applied for patents on his methods. He said he chose embryo gene editing for HIV because these infections are a big problem in China.

Either way, it will be a long time before we know for sure what the cerebral impacts of the experiment turn out to be.

‘Could it be conceivable that at one point in the future we could increase the average IQ of the population? I would not be a scientist if I said no,’ Silva concludes.

‘The work in mice demonstrates the answer may be yes,’ he said.

‘But mice are not people. We simply don’t know what the consequences will be in mucking around. We are not ready for it yet.’

Source: Read Full Article