For some years now John McGeehan, a biologist and the director of the Center for Enzyme Innovation in Portsmouth, England, has been searching for a molecule that could break down the 150 million tons of soda bottles and other plastic waste strewn across the globe.

Working with researchers on both sides of the Atlantic, he has found a few good options. But his task is that of the most demanding locksmith: to pinpoint the chemical compounds that on their own will twist and fold into the microscopic shape that can fit perfectly into the molecules of a plastic bottle and split them apart, like a key opening a door.

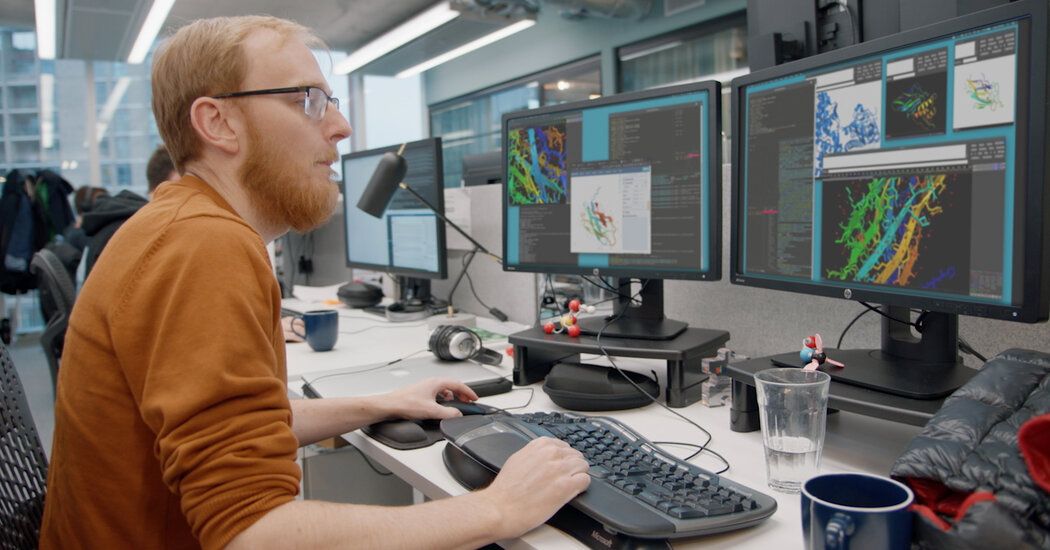

Determining the exact chemical contents of any given enzyme is a fairly simple challenge these days. But identifying its three-dimensional shape can involve years of biochemical experimentation. So last fall, after reading that an artificial intelligence lab in London called DeepMind had built a system that automatically predicts the shapes of enzymes and other proteins, Dr. McGeehan asked the lab if it could help with his project.

Toward the end of one workweek, he sent DeepMind a list of seven enzymes. The following Monday, the lab returned shapes for all seven. “This moved us a year ahead of where we were, if not two,” Dr. McGeehan said.

Now, any biochemist can speed their work in much the same way. On Thursday, DeepMind released the predicted shapes of more than 350,000 proteins — the microscopic mechanisms that drive the behavior of bacteria, viruses, the human body and all other living things. This new database includes the three-dimensional structures for all proteins expressed by the human genome, as well as those for proteins that appear in 20 other organisms, including the mouse, the fruit fly and the E. coli bacterium.

This vast and detailed biological map — which provides roughly 250,000 shapes that were previously unknown — may accelerate the ability to understand diseases, develop new medicines and repurpose existing drugs. It may also lead to new kinds of biological tools, like an enzyme that efficiently breaks down plastic bottles and converts them into materials that are easily reused and recycled.

“This can take you ahead in time — influence the way you are thinking about problems and help solve them faster,” said Gira Bhabha, an assistant professor in the department of cell biology at New York University. “Whether you study neuroscience or immunology — whatever your field of biology — this can be useful.”

This new knowledge is its own sort of key: If scientists can determine the shape of a protein, they can determine how other molecules will bind to it. This might reveal, say, how bacteria resist antibiotics — and how to counter that resistance. Bacteria resist antibiotics by expressing certain proteins; if scientists were able to identify the shapes of these proteins, they could develop new antibiotics or new medicines that suppress them.

In the past, pinpointing the shape of a protein required months, years or even decades of trial-and-error experiments involving X-rays, microscopes and other tools on the lab bench. But DeepMind can significantly shrink the timeline with its A.I. technology, known as AlphaFold.

When Dr. McGeehan sent DeepMind his list of seven enzymes, he told the lab that he had already identified shapes for two of them, but he did not say which two. This was a way of testing how well the system worked; AlphaFold passed the test, correctly predicting both shapes.

It was even more remarkable, Dr. McGeehan said, that the predictions arrived within days. He later learned that AlphaFold had in fact completed the task in just a few hours.

AlphaFold predicts protein structures using what is called a neural network, a mathematical system that can learn tasks by analyzing vast amounts of data — in this case, thousands of known proteins and their physical shapes — and extrapolating into the unknown.

This is the same technology that identifies the commands you bark into your smartphone, recognizes faces in the photos you post to Facebook and that translates one language into another on Google Translate and other services. But many experts believe AlphaFold is one of the technology’s most powerful applications.

“It shows that A.I. can do useful things amid the complexity of the real world,” said Jack Clark, one of the authors of the A.I. Index, an effort to track the progress of artificial intelligence technology across the globe.

As Dr. McGeehan discovered, it can be remarkably accurate. AlphaFold can predict the shape of a protein with an accuracy that rivals physical experiments about 63 percent of the time, according to independent benchmark tests that compare its predictions to known protein structures. Most experts had assumed that a technology this powerful was still years away.

“I thought it would take another 10 years,” said Randy Read, a professor at the University of Cambridge. “This was a complete change.”

But the system’s accuracy does vary, so some of the predictions in DeepMind’s database will be less useful than others. Each prediction in the database comes with a “confidence score” indicating how accurate it is likely to be. DeepMind researchers estimate that the system provides a “good” prediction about 95 percent of the time.

As a result, the system cannot completely replace physical experiments. It is used alongside work on the lab bench, helping scientists determine which experiments they should run and filling the gaps when experiments are unsuccessful. Using AlphaFold, researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder, recently helped identify a protein structure they had struggled to identify for more than a decade.

The developers of DeepMind have opted to freely share its database of protein structures rather than sell access, with the hope of spurring progress across the biological sciences. “We are interested in maximum impact,” said Demis Hassabis, chief executive and co-founder of DeepMind, which is owned by the same parent company as Google but operates more like a research lab than a commercial business.

Some scientists have compared DeepMind’s new database to the Human Genome Project. Completed in 2003, the Human Genome Project provided a map of all human genes. Now, DeepMind has provided a map of the roughly 20,000 proteins expressed by the human genome — another step toward understanding how our bodies work and how we can respond when things go wrong.

The hope is also that the technology will continue to evolve. A lab at the University of Washington has built a similar system called RoseTTAFold, and like DeepMind, it has openly shared the computer code that drives its system. Anyone can use the technology, and anyone can work to improve it.

Even before DeepMind began openly sharing its technology and data, AlphaFold was feeding a wide range of projects. University of Colorado researchers are using the technology to understand how bacteria like E. coli and salmonella develop a resistance to antibiotics, and to develop ways of combating this resistance. At the University of California, San Francisco, researchers have used the tool to improve their understanding of the coronavirus.

The coronavirus wreaks havoc on the body through 26 different proteins. With help from AlphaFold, the researchers have improved their understanding of one key protein and are hoping the technology can help increase their understanding of the other 25.

If this comes too late to have an impact on the current pandemic, it could help in preparing for the next one. “A better understanding of these proteins will help us not only target this virus but other viruses,” said Kliment Verba, one of the researchers in San Francisco.

The possibilities are myriad. After DeepMind gave Dr. McGeehan shapes for seven enzymes that could potentially rid the world of plastic waste, he sent the lab a list of 93 more. “They’re working on these now,” he said.

Source: Read Full Article