Political and environmental meltdowns have dominated newspaper headlines for most of 2019.

So why not put the chaos on Earth behind us and start afresh in space?

The evangelists of Asgardia, the ‘first space nation’, believe that the problems of Earth should not be replicated in space when, they believe, people start moving there.

‘It would be dangerous to take with us the huge baggage of problems accumulated over millennia,’ says Igor Ashurbeyli, the founder and head of nations of Asgardia.

He hopes to lay the political and legal foundations for a new type of nation, one that ‘sees no borders’.

Since its formation in 2016, Asgardia now boasts a constitution and a parliament that serves almost 20,000 citizens around the world.

In exchange for €100 (£86), citizens receive a handful of Solar – Asgardia’s own cryptocurrency – and the opportunity to upload their photo to a small satellite that orbits the Earth.

They can even sing Asgardia’s national anthem, which is as earnest as the national anthems of most Earth-bound nations.

We’ve been here before: Nasa announced in 2006, under President George W Bush’s Vision For Space Exploration, that a permanent research station on the moon would be in place by 2020.

Unless something dramatic happens in the next 14 months, that will not happen.

But of course, Ashurbeyli, who almost entire funds Asgardia, is not the only billionaire with space ambitions:

What would a space society look like?

What would a space society look like?

On the technology front, Elon Musk’s company SpaceX and Jeff Bezos’ company Blue Origin have made the most progress towards creating a society in space.

So what makes Asgardia any different?

‘Unlike Elon Musk, we don’t aspire to place one million people on Mars, Ashurbeyli tells Metro.co.uk.

‘Until we can get a child to be born in space, no such mission makes sense because the people who go on those missions will never return.’

Ashurbeyli also notes the ‘discrimination’ that runs through most efforts to colonise space.

‘Only about 20 countries out of 229 have access,’ he says, describing national space agencies as ‘selfish’.

Democratising access to space is one of Asgardia’s chief goals, alongside the preservation and expansion of humanity.

‘The idea that the human race is going to sit at home watching daytime TV for the rest of eternity when there’s an entire universe inviting us to visit is ridiculous,’ says Lembit Öpik, the chairman of Asgardia’s parliament, former Liberal Democrat MP and sometimes daytime TV guest.

But first they must figure out how to give birth to an Asgardian in space, which Ashurbeyli predicts will happen by 2041.

There are many unknowns and concerns when doing this.

The Space Life Origin project in the Netherlands wanted to send a pregnant woman 250 miles above Earth to give birth in 2024 as a world – or near space – first.

It is currently indefinitely suspended because of ‘serious ethical, safety and medical concerns’ and ‘not realistic’ to fund.

For Asgardia, the effects of cancer-causing cosmic rays on astronauts are still largely unknown and would make giving birth and raising a child in space especially hazardous.

The differences in gravity on a spacecraft or off-world colony throw up other unknowns and risks and could mean infants grow into quite different bodies.

No expert can say with confidence the impact that being born in space or an artificial environment could have on a baby.

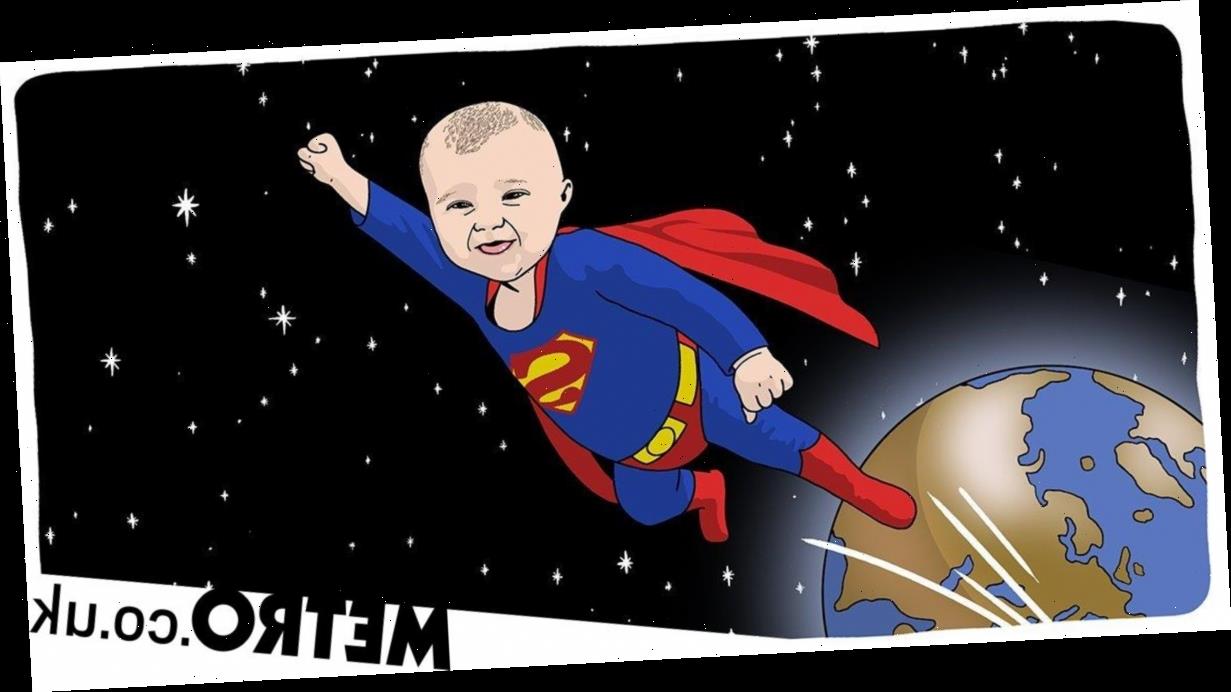

‘You could be a kind of Superman,’ says Öpik.

‘That was the whole idea of Superman. He came from a planet which had far higher gravity than the Earth.’

Speaking at Asgardia’s first Space Science and Investment Congress last week, neuroscientist Jeffrey Alberts says that people born in space could even have different brains to those on Earth, with some senses heightened and others diminished.

Calling this difference the ‘astroneurone’, he warned that space-born humans could be seen as deficient but encouraged such adaptations to be appreciated as part of humanity’s incredible diversity.

With the possibility of a space birth looming in the coming decades, Asgardia wants to create a new political and legal framework not tied to any Earth nation.

‘What would it mean to be born on the moon and then be told that you’re American?,’ says Öpik.

‘It doesn’t make any sense.’

Such space societies are a mainstay of science fiction, from the pioneering spaceship designs of Russian rocket scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in the 19th century, to Stanley Kubrick’s visionary 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Asgardia’s depiction of a fleet of Space Arks that would orbit the Earth to ensure the survival of humanity is equally ambitious and still in the realm of science fiction.

So is the Space Nation just another billionaire’s vanity project?

The best of The Future Of Everything

A weekly look into the future (new pieces every Wednesday morning)

The future of Numbers: What comes after the giga, tera, peta, exa, zetta and yottabyte?

The future of People: Racism ‘won’t go away’ even if we’re all mixed-race in the future

The future of Travel: Commuting is miserable right now – but the future will change that

The future of Space: There is a chance we will be able to travel through dimensions and time

The future of Evolution: What are the hard human limits of athletic world records?

The future of Love: People could be happier with open relationships rather than hunting for ‘the one’

The future of Technology: Graphene the ‘miracle material’ is stronger than diamond but what can it do?

The future of Health: Gene editing: will it make rich people genetically superior?

The future of Power: Multinationals like Facebook want to wrestle control of the monetary system away from nation states

The future of Work: Your boss is already reading your emails. What happens when they can track your every move?

‘The amount of time and energy that you have to invest and the scope of problems you might have to overcome to open your own shoe store is equivalent to many significantly more ambitious projects,’ Ashurbeyli tells Metro.co.uk.

‘You only have 24 hours in each day and only two hands. So I thought what could be the most ambitious project to deal with?’

Asgardia’s Constitution does give a few more concrete examples of what Asgardian society would look like.

Political parties and public religion are banned in Asgardia, which Ashurbeyli hopes will lead to a peaceful society free from the conflicts of Earth.

It’s a utopian, but a potentially autocratic blueprint for future civilisation. Critics also question the diversity of future space societies like Asgardia.

Around 80% of Asgardians are men and the leading ranks of Asgardia’s Parliament could be described as largely pale, male and stale.

Still, Öpik paints an optimistic picture of what life in space would be like:

‘In many ways, it’ll be like life on Earth,’ he says.

‘People will have arguments, they’ll fall in love, they’ll fall out of love, they’ll have children.

‘They’ll look out the window and amazing views and sometimes they’ll complain about the space weather.’

Facing deadly solar winds, and a distinct lack of rain – except for the occasional meteor shower – there would be plenty to complain about.

And the demands of sustaining life in such a hostile environment makes raising children especially challenging for any prospective space-parents:

What is Asgardia?

One of the first Asgardian projects will be the creation of a network of satellites to protect the Earth from space hazards such as asteroids, solar flares and orbiting man-made debris.

Asgardia is named after the City of the Gods in Norse mythology.

Its main aim is to develop space technology unfettered by Earthly politics and laws, leading ultimately to a permanent orbiting home where its citizens can live and work.

People can apply online to be Asgardian citizens via its website.

Those already recognised as citizens are now being asked to vote on key elements of the Asgardian constitution.

Asgardia-1, launched on November 12, 2017, was roughly the size of a loaf of bread, measuring just 20cm (eight inches) long and weighing about 2.3kg (5lbs).

It contained a solid-state hard drive containing the citizen data of the first Asgardians and two particle detectors for measuring radiation levels in space.

‘It takes two parents to have a child,’ says Öpik.

‘Maybe it takes the whole planet to raise a child.’

Asgardia’s democratic ideals will unlikely translate into an affordable ticket into space anytime soon.

Öpik acknowledges that virtual reality is a more practical near-term way for many Earth-bound Asgardians to travel to space.

But when people start experiencing the harsh realities of life in space, the more Earth-bound society may appreciate the oasis our planet provides.

‘We are a tiny, tiny, tiny, little rock in an advanced universe, and it’s the only spaceship that we have: it’s Spaceship Earth,’ Belgian astronaut Frank de Winne told an audience at Asgardia’s Congress.

‘We need to find solutions in space. But we need to make sure that when we do [venture into space] that we don’t make the mistakes that we did in colonising our planet.’

What happens to our ‘tiny little rock’ in the next century is a fascinating question.

Lembit Opik and others think that moving to space could be a realistic proposition before the century is over.

A Nobel Prize-winning astrophysicist thinks that is a very stupid idea.

The Future Of Everything

This piece is part of Metro.co.uk’s series The Future Of Everything.

From OBEs to CEOs, professors to futurologists, economists to social theorists, politicians to multi-award winning academics, we think we’ve got the future covered, away from the doom-mongering or easy Minority Report references.

Every week – new pieces every Wednesday morning – we’re explaining what’s likely (or not likely) to happen.

Talk to us using the hashtag #futureofeverything If you think you can predict the future better than we can or you think there’s something we should cover we might have missed, get in touch: [email protected] or [email protected]

Read every Future Of Everything story so far

Source: Read Full Article