They don’t want to sell this as a revolution.

“It’ll be very similar to more of a traditional camp,” Jeremy Hefner, the Mets’ new pitching coach, said of the upcoming spring training for his new charges. “They’ll throw their bullpens, and then live [batting practice] and we’ll start getting into games.”

“The thing I want to reiterate to them the most is, we don’t need to change anything,” Matt Blake, the Yankees’ new pitching coach, said on the same topic. “What we need to understand is, if there are things you want to know more about, we can facilitate those conversations.”

Fair enough. Yet if this doesn’t constitute a revolution, call it one heck of an evolution. Imagine if it took only five years, rather than two million, for apes to transform into human beings and you have a sense of how rapidly the analytics age has enveloped Major League Baseball — most prominently, one could argue rather easily, on the pitching side.

“A lot has changed,” said Phillies manager Joe Girardi, who as a former catcher has been working closely with pitchers for more than 30 years. “There’s so much more information available to us.”

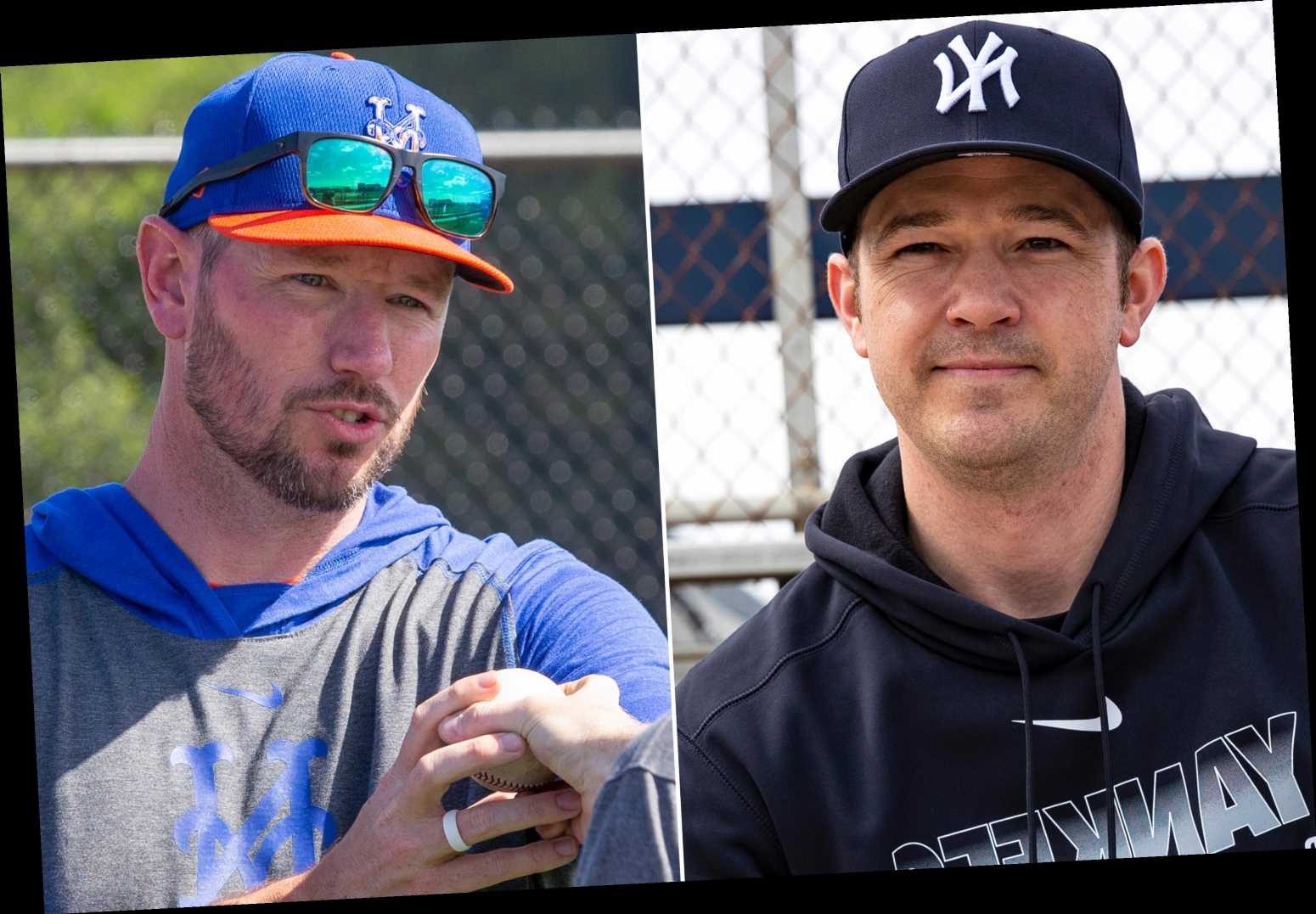

The two New York teams have gone all-in on the information, on the evolution. A year ago, the Yankees and Mets deployed Larry Rothschild and Dave Eiland, men with a total of 40 years of major league coaching/managing experience and two World Series rings apiece, to run their pitching operations. While age need not be an anathema to this new wave — the Astros have thrived under 71-year-old pitching coach Brent Strom, Rothschild became the Padres’ pitching coach and Eiland elevated Jacob deGrom and Zack Wheeler to new heights while with the Mets — Blake, 34, and Hefner, 33, will run big-league pitching staffs for the first time on the hopes that their comfort with the accessible technology and tidbits will offset their service-time deficits.

The tidbits emanate from the technology, and while every team injects its own secret sauce into the process, all 30 clubs get tethered by this new reality: Nothing goes unmonitored, uncounted, anymore. From the moment a pitcher reports to preseason camp until his team’s season concludes, every pitch he throws — be it in the bullpen, throwing live BP in spring training or in Game 7 of the World Series — should get recorded and then added to the pitcher’s database.

Baseball’s “Statcast Era” began in 2015, at which point Major League Baseball had installed TrackMan radar technology in each of its 30 ballparks. TrackMan proved exceptionally apt at tracking a pitch’s movement (as well as a batted ball’s flight, for exit velocity and launch angle). When clubs desired to collect that information on pitches thrown outside of game action, primarily in the bullpen both home and away, they invested in portable units, first manufactured by Rapsodo, which use both radar and optical technology. Teams have found the Rapsodo device particularly helpful in tracking a pitch’s spin, and the unit’s viability enabled teams to view all pitches, be they in games or out, through the same objective prism.

That the TrackMan is being replaced in 2020 by the HawkEye, optical technology best known for its work in tennis (determining whether shots are in or out), shows just how quickly everyone must keep up — not only the teams and their pitchers, but the companies that fueled this industry. TrackMan sells a portable contraption of its own, enabling it to stay in the game.

The Edgertronic high-speed camera, meanwhile, opened up another window for teams and their pitching gurus. With the ability to shoot 500 frames per second at its highest resolution, it slows down the action for pitchers and their coaches to dissect. For the first time, people could see clearly a most basic interaction, that between the hand and the ball.

These gadgets and their gigabytes produce multiple benefits. Most important, they can play a critical role in health maintenance and injury prevention. An unintentionally altered release point can reflect fatigue and the need for rest. Left unchecked, a pitcher’s tweaked hip movement can lead to a malady. This equipment dramatically decreases the likelihood of such a development going unchecked. Teams’ integration of biomechanics experts, like the Yankees’ hiring of Eric Cressey, into their conditioning and coaching systems further emphasizes this focus.

And once the pitcher stays upright, he can succeed easier with all of the facts and figures accessible to him. The newfangled statistics can serve as both the causes and effects of improved performance. A team can encourage a pitcher to drop a pitch he’s trying to develop, for instance, if the underlying data doesn’t support its viability. Every pitch carries a smorgasbord of details, from release point (the number of feet from home plate a pitcher actually lets go of the ball) to spin rate (the number of revolutions per minute — the more, the better) to vertical and horizontal break and more.

“I just think the gap between adjustments is a lot shorter now,” Hefner said. “Instead of month-to-month or season-to-season or half-season-to half-season, it could be game-to-game, or at-bat to at-bat. The onus is on players to make that adjustment, to actually execute on the adjustment, but the identification of the need for an adjustment is much more readily available.”

Enter the pitching coach, whose mission more than ever is to master all of this information and its collection, digest it and choose how to best present it, individually, in order for that adjustment to take flight.

Of the two Big Apple newcomers, Hefner carries the more traditional profile. Drafted and signed by Sandy Alderson’s Padres in 2007 and then selected off waivers (from the Pirates) by Alderson’s Mets in 2011, Hefner pitched in a total of 50 games for the Mets in 2012 and 2013, tallying a 4.65 ERA, before a pair of Tommy John surgeries on his right elbow sidelined him, and he never returned to the big leagues. He retired early in 2017 and spent the next two seasons as a Twins advance scout, working primarily around the big-league club as he assisted in game-planning for both the pitchers and the hitters. The Twins promoted him to assistant pitching coach for 2019, during which they won their first American League Central title since 2010, and another promotion brings him back to Citi Field.

“I’ve always kind of been a process-oriented person,” Hefner said. “I like to follow steps and procedures. I don’t like to be surprised. I like to be prepared. I always wanted the information [as a pitcher]. It’s easier for me to make decisions that way.”

Last year, Hefner worked under Wes Johnson, himself very much a new sign of the times. The Twins hired Johnson from the University of Arkansas, making him the first pitching coach to ever jump directly from the college level to the big leagues.

“When you look at where pitching is going, there’s this balance that has to happen,” Johnson told The Post. “That balance of some things that were done in the past with the new-school stuff: The Edgertronics, the biomechanics. It’s another thing that Hef does well. His experience as a pitcher is going to be able to balance that with all of these guys.”

Johnson also knows Blake from their interactions in the pitching fraternity. “Matt’s phenomenal with [a pitchers’] delivery, analytics,” he said. Johnson and Blake share less conventional paths to the top, in that neither man played professionally.

Blake grew up in New Hampshire. His father, Carroll Blake, coached him as a youth-league pitcher, yet he might have prepared his son even more by the way he functioned off the field.

“He liked to dig into things,” Blake said of his father. “I liked watching how he worked a process to understand the different mechanisms, like taking a car apart, or building our house.”

Similarly, after his pitching career concluded at Holy Cross, Blake began a job in sales with aspirations of getting right back into baseball.

“I didn’t understand the mechanics of pitching as much as I wanted to,” Blake said. “That sent me down the rabbit hole of learning about mechanics and kinesiology. I started trying to get my hands on textbooks about pitching.

“A lot of it was classic jargon about delivery, very rooted in baseballisms and not much about fundamental movement. So I read more about track and field and golf. Looking at the swing, the throw, someone’s running, I thought, ‘It seems like there’s a place to have that conversation in baseball.’”

Many agreed with him, including Cressey, who hired Blake to work at his institute in Massachusetts. Blake’s first professional job came with the Yankees, working as an assistant coach, and he spent the last four years climbing the ladder with the Indians, who had promoted him to pitching director just days before he left for the Yankees.

In Cleveland’s organization, Blake spent time with Steve McCatty, in many ways his biographical opposite. McCatty pitched in the majors for nine years, placing second in the 1981 American League Cy Young Award voting, and served as the Tigers’ pitching coach in 2002 and then the same job with Washington from 2009 through 2015. The Indians hired him to coach their Single-A Lake County Captains in 2016 as Blake began his first job there as a lower-level pitching coordinator.

“It was probably a little bit of an intimidating situation [for Blake] at first. Here’s some guy that’s got some experience in the big leagues,” McCatty said in a telephone interview. “But he handled it well. He started giving it back as good as he got toward the end of spring training.

“He would come up, and we had a lot of good conversations. I really enjoyed Matt. He’s an intelligent guy, and I don’t think he’s wrapped up in saying, when you look at something, ‘This is 100 percent the way it’s going to be.’ You’ve got to take what the player does.”

No matter how sophisticated the equipment gets, no matter how scientific the metrics become, the evolution’s beneficiaries and casualties agree that the basic principles of coaching won’t change.

“I don’t like the ‘old-school, new-school’ terms,” Hefner said. “Being able to have a relationship with the player, that will never go away. TrackMan’s great. Rapsodo is good. Edgertronic is great. Motion-capture technology is incredibly helpful. They all serve a purpose just like any tool.

“If you have someone who can use the tool the best, that’s where you can [prevail].”

Pricey tools, young practitioners. Can the Yankees or Mets evolve right into a parade? The success rates of Blake and Hefner will go a long way toward reaching that ultimate goal.

Source: Read Full Article