Now, let me tell you what it was like growing up in a home for the mentally ill.

When I was ten years old and in Grade 5, my life changed big time. Mom’s husband, Harold, was fired. He’d worked at Sterling Drug in Aurora as a production planner. He was a very good worker. Got promotions and all that. Then, all of a sudden, he got his walking papers. It was a puzzlement to everyone at the time, but looking back, it makes sense. He was probably stealing drugs for Mom and got caught.

Advertisement

Harold was out of a job, so Mom started doing home care for the inmates at Martin Acres. She liked it there. She was in charge of handing out the medications. The men took all kinds of pills. The owners, Al Martin and his wife, were getting older and were talking about retiring, but they had no succession plan. Mom went to them and offered them a deal. Harold owned an eleven-room house in Aurora. How would the Martins like to trade Harold’s house for the business of running the rehabilitation centre? The Martins agreed on the condition that they kept ownership of the land and building. All Mom and Harold had to do was pay for the utilities. Mom and Harold jumped on it, and Harold signed over the house he and his first wife, Rose, had worked tremendously hard for.

I had no idea we were moving. I found out one day after school. There was no conversation about it, just “Get in the station wagon.” We pulled up past a sign that said martin acres and onto the driveway that ran in front of the house. Harold told me to hop out and unload my stuff. That wasn’t hard because I had only a few shirts, a couple of pairs of underwear and three pairs of socks, two sweatshirts, one pair of blue jeans, a pair of cords and my hockey cards. My whole world in one suitcase.

I followed Harold through the front door, then through another door, up the stairs to the right, above the garage. There were four bedrooms up there. He pointed to the first room on the right. “This is yours,” he said. The other doors were all opened a crack and I could feel several pairs of eyes watching.

Advertisement

I found out later that my room was with the men who were on the calm side. The other side was a little more dangerous.

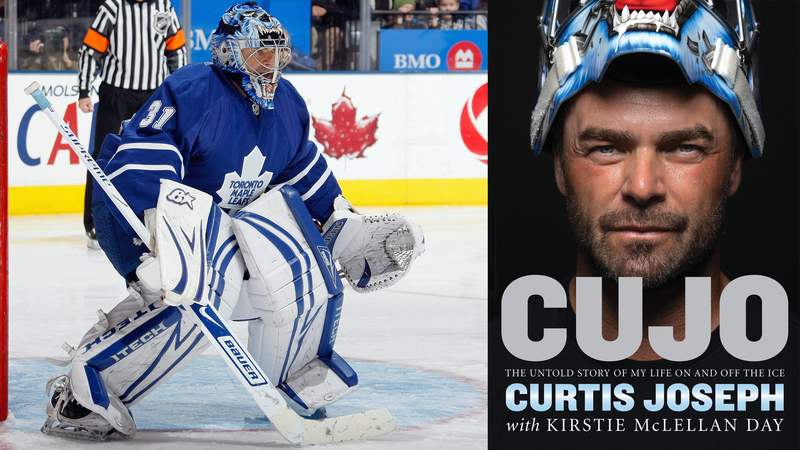

Cujo: The Untold Story of My Life On and Off the Ice

Wellington was a pedophile, for sure. He was a big, meaty Black guy, sweaty and bald. He didn’t talk a lot and he had a strange way of looking at you. Karen told me later that all the men were on some sort of castration medication, but Wellington would follow me down to the potato cellar and flash me. When I was down there, I’d hear a creak on the top step and I’d fill the bag as fast as I could and then hide. But he’d stand at the bottom of the stairs and wait for me to come out. I did my best to avoid him. Any time I had to go anywhere on the property where there was a possibility he could corner me, I kept my head on a swivel.

Advertisement

I finally told Harold about Wellington’s habit. It was the first of two times I saw Harold get really mad. The other time resulted in a violent fight with my brother Grant. The memory of that fight still bothers me to this day. I’ll get to it later.

Harold found Wellington and threatened to beat the ever-livin’ tar out of him. No swearing—Harold wouldn’t swear. I felt good about Harold sticking up for me, but it didn’t change anything until the day Wellington tried it with Mom. There was a laundry room downstairs near the dining hall. Mom was in there, ironing, and he came up beside her and exposed himself. Mom didn’t hesitate. She lifted the hot iron and tapped it on the tip of his penis. Wellington stayed out of the laundry room after that.

Tony was an Italian guy in his mid to late thirties. He was about five foot ten and roly-poly, with dark eyes and olive skin. He was probably the youngest and best-looking guy at Martin Acres. Tony wasn’t all there upstairs, but he took care of himself. You could see the comb marks running in neat rows through his thick black hair. He wore it long on top and slicked back.

Advertisement

Tony obsessed about his “thirteen imperfections.” If you went anywhere near him, he’d tell you, “I have thirteen imperfections.” And then he’d show you a freckle or mole. We were all told not to go out behind the barn because Tony might be lying in the sun, stark naked, out there. Sometimes he’d sit by a window in the commons room, take his shirt off and suntan. I guess it was his way of trying to get rid of his thirteen imperfections.

The patients rarely had visitors. I mean, nobody visited these people. Tony was one of the few guys whose family came by. They saw him a couple of times a year and they dressed well and drove nice cars. I never thought about what I didn’t have or what I did without, but they seemed rich to me.

Little George would sit in the same worn leather chair in the vestibule, at a table for two, every day. He was a short, portly Jewish guy. He had blue eyes and a big smile, although he was ornery a lot of the time. He complained a lot—he wasn’t getting enough food, he needed more cigarettes. “Where’s my medication?” Stuff like that.

Advertisement

His job was to empty the wastepaper basket. He’d been a lawyer, but one day, crossing the street in Toronto to get a Globe and Mail newspaper, he didn’t see a truck coming at him from around the corner. It rolled over him and the back of his coat got caught in the undercarriage and he was dragged. His cranium bouncing off the pavement for a fair distance caused brain damage. If you put garbage in the wastebasket he’d say, “Whoop! Whoop! Garbage, garbage, garbage,” grab the wastebasket and off he’d go to Harold’s big burn barrel out back. He was like Charlie Chaplin in the way he moved—really fast, but with a wiggle because he took such short little steps.

Karen came by a fair bit to help wash walls or take care of the patients whenever Mom and Harold went away. She’d rip a page out of a newspaper, ball it up, walk past George and drop it in the wastebasket. “Whoop! Whoop! Garbage, garbage, garbage!” And off Little George would go to the burn barrel. It seemed to make him happy.

Little George was a midnight raider. When people were sleeping, he’d sneak into their rooms and collect their socks and combs. In the morning, Rose, the lady who helped clean up for the men, would gather whatever he stole during the night and put it all back.

Advertisement

Little George’s son would come visit every month or so, and when he came, he brought chocolate bars for all the men. Little George lived at Martin Acres for the rest of his life. He died long after we left. He wandered off unnoticed and walked in front of a train only two miles from the house. It was shocking because I’d known him for ten years. Brilliant lawyer at one time, from what I was told.

Big George—there was a Big George and a Little George—was a nice soul, a great soul. We knew him the best. He was the closest to us, like part of the family. He was tall, very tall—probably six foot three— and he stunk of BO. It was bad. He would have been in his fifties. He had white hair with a thinning comb-over and was kind of funny-looking because of his big features—big ears, big nose. Big George talked to himself a lot.

Big George’s parents were good friends with the original owners, Al Martin and his wife. When he was eleven, there was a car accident and both parents were killed. George sustained a head injury that resulted in brain damage. It halted his intellectual and emotional growth. No matter how old he got, he was forever eleven years old.

Advertisement

Big George liked to do dishes and odd jobs. He would always ask, “Can I do somethin’? Can I do somethin’?” And Harold would give him little tasks to do. He was friendly, quiet, congenial and curious. He was always lurking around the corner whenever adults had a conversation. If he was doing dishes and Harold and Mom were talking, George would stop washing the dishes, drop his hands in the water and just stand there, listening.

Harold would tell him, “Okay, George, come on, finish up the dishes there.”

George would nod. “Okay, Harold.”

Big George didn’t like it if Grant and I fought, even if it was a play fight. We’d tease him by pretending to wrestle and that would make him lose his mind. Every time. Like clockwork. His tongue would come out of his mouth and his eyes would pop open wide and his face would start twitching. I know it sounds mean, but honest to God, it was funny.

Advertisement

Ding Wong was a slender Chinese guy. Very skinny. Early forties, maybe. He had long nails and fingers yellowed with nicotine. Most of the inmates were like that because they smoked so much. Ding walked and walked and walked and walked. He’d leave the commons room, walk through the vestibule and out the door. He did this day after day, and eventually he wore a path all the way around the building.

While he was walking, he would just lose it and start screaming at the top of his lungs in Chinese, like he was being bombed in the middle of a war. And then he’d pivot and start walking fast around the house in the other direction.

When Karen came to visit, she sometimes wore this soft, fuzzy, colourful pullover sweater—red, yellow and blue stripes like the rainbow. Ding would come up to her and run his hand up and down the sleeve and say, “Nice, nice, nice. Like! Like! Nice, nice. Like!” He was absolutely in love with this sweater. One day, she gave it to him. He put it on and wore it all the time after that. Mom used to argue with him about it because he wouldn’t let her wash it.

Advertisement

There was also a Big Albert and a Little Albert. Little Albert was short but wide. Harold did all the cooking for the men, but Little Albert helped in the kitchen. Now, he didn’t do meat, and he didn’t do all of the cooking, but he helped make the soup of the day. That meant chopping up all the potatoes, carrots, turnips, vegetables . . . that kind of stuff. Little Albert mostly kept to himself, but he was nice. Always had a kind smile. He came to a sad end. Years after we moved out and the home was taken over by someone else, Albert went out the side fire-escape door for a smoke and stood on the stairs. Somehow, he fell through, broke his neck and died.

Big Albert was a monster of a man. Huge. Over six feet and about 350 to 380 pounds. He was bald on the top but had hair around the sides like Friar Tuck.

I was told he’d been a professional wrestler, kind of a violent guy. The story goes that he lost his cool and killed somebody. That’s why they sent him to Nine Ninety-Nine and gave him a frontal lobotomy, which made him gentle as a lamb.

Advertisement

Once they saw he had been rendered harmless, he came to live at Martin Acres. He was strong as an ox. I remember him helping Harold move his big Wurlitzer organ through to the living room. It wasn’t like the digital organs you see now. It was a big, walnut-cased, two-keyboard reed organ with pedals and it took up a lot of space in our apartment inside the house. Big George lifted his end up like it was a box of oranges. But when they got to the doorway and Big Albert went to shove the instrument through it widthwise, Harold had to stop him and tell him to turn it lengthwise. Because of the lobotomy, Big Albert had lost his ability to figure that out himself.

Big Albert would lie in his bed every night, repeating over and over, “I’m dead. I’m in the morgue. I’m dead. I’m in the morgue.” One time, Karen was sleeping in the room below and it was driving her crazy. She hopped out of bed, ran up the stairs and gave him a little pinch on his arm.

He said, “Ow!”

She said, “Did you feel that?” “Yes,” he said. “That hurt!”

“Well, then, you’re not dead in the morgue. Now stop it and go to sleep.”

We had an architect living there. I don’t remember his name. Maybe because he was nonverbal. Tall, slim, salt-and-pepper blondish hair, blue eyes. Good-looking guy. German, I think. Mom and Harold had to guard all the pencils because if he got hold of one, he wrote all over the walls in tiny, tiny, tiny print. Not random drawings—numbers. Measurements. He didn’t have a tape measure or anything like that. He wrote down what was in his head—widths, heights and lengths.

Advertisement

He had a bit of a phobia about kitchens. When Mom gave out medication, she’d leave his little glass of juice and his pills on the kitchen table and call him to the door. He would come to the doorway and not move until she stepped up the small stairway into the dining room. She’d watch him come up to the table, pull out the chair, sit down, take his pills, shoot back the juice, turn around, open his mouth, lift his tongue to show her that they were all gone and walk out of the room.

This happened only in the kitchen. He’d sit in the commons room and eat with the others in the dining room. But there was no way he was coming into that kitchen while anybody else was there.

There was another guy—Dave. I didn’t know much about him, but he came with long hair, really scraggly. He was brain-damaged from drugs, for sure. He looked like what you might think a heroin addict would look like. Absolutely fried.

Advertisement

He’d been a drummer in a band, took too much of something and burned his brains out. Harold played the organ all the time—the same Wurlitzer Big George helped him move. Church music—“How Great Thou Art” is one of the songs that still rolls around in my head. As a fellow musician, I think Harold felt for Dave.

Dave didn’t say much. Life was a lot different for him than when he was in the band. He went from giving the finger to the establishment to being institutionalized. Harold cut his hair, like he did with all the men, because they couldn’t risk lice, and he was issued government clothing. Pretty demoralizing for a guy like Dave. He’d sit in a chair across from Little George at the table for two in the vestibule, chain-smoking and staring at the floor. I think Harold worried that Dave was depressed.

He hadn’t been with us very long when Harold spotted a full set of second-hand drums in the classifieds. He decided to buy them for Dave. He didn’t check with Mom, so he caught hell for it later, but it was worth seeing Dave’s face light up when he led him out to the barn where they were all set up. And, as much as Dave’s mind was gone, he could really play those drums. He’d sit out there for hours, banging out songs like Iron Butterfly’s “In-a-Gadda-da-Vida” or “100,000 Years” like Kiss’s drummer, Peter Criss.

Advertisement

Like I said, Harold was a very kind and compassionate person. But he wasn’t my dad. He wasn’t interested in being fatherly to me. When I think of Harold, I think of him more as—a guardian, you know? I can’t remember him ever giving me advice or anything like that. Mostly “Go water the garden, go weed the garden.” The garden was his thing. I picture him in a straw hat, riding on his mower through this magnificent vegetable garden with stalks of corn and tall, fluttery sunflowers. Looking back, it taught us about hard work, because the garden was huge. Massive. It was half an acre.

I spent a lot of time with Harold in the car because he drove me to and from school. We moved to Martin Acres in Sharon while I was still at Whitchurch Highlands. They didn’t make me change schools. Harold would drive me from Sharon to the school-bus stop, and then coming home I’d take the bus from school to the same stop—the bus didn’t stop anywhere near our place. The plan was that I’d wait outside a gas station a few miles from Martin Acres for Harold to come and get me. Trouble was, Harold had narcolepsy. He would actually fall asleep while playing the organ. That meant I might wait until all hours of the night for my ride. Eight, nine, ten o’clock. From Grade 5 to Grade 8. Three or four times a week. He’d rarely be on time. But I’d have a hockey stick with me, and a ball. I’d spend most of that time shooting it against a tall propane tank shaped like a rocketship. Sometimes it got extremely cold and my fingers froze up, which meant I couldn’t hold the stick. I remember jumping up and down, just shivering. I was too shy to ask the attendant to use the bathroom. There were occasions when I’d pee my pants, but in the end, waiting for Harold was a great thing because I used the time to learn to handle the puck.

This excerpt from Cujo: The Untold Story of My Life On and Off the Ice by Curtis Joseph with Kirstie McLellan Day is printed with the permission of Triumph Books. For more information and to order a copy, please visit www.triumphbooks.com/Cujo.

Advertisement

Cujo: The Untold Story of My Life On and Off the Ice

Source: Read Full Article