There was a light rain falling at the Polo Grounds just past 3 o’clock that muggy Monday afternoon, 88 degrees and humid, but the clouds weren’t threatening. There were 21,000 people in the stands, and there were two pennant contenders eager to face off with each other. It never occurred to home plate umpire Tommy Connolly to do anything but bark “play ball!”

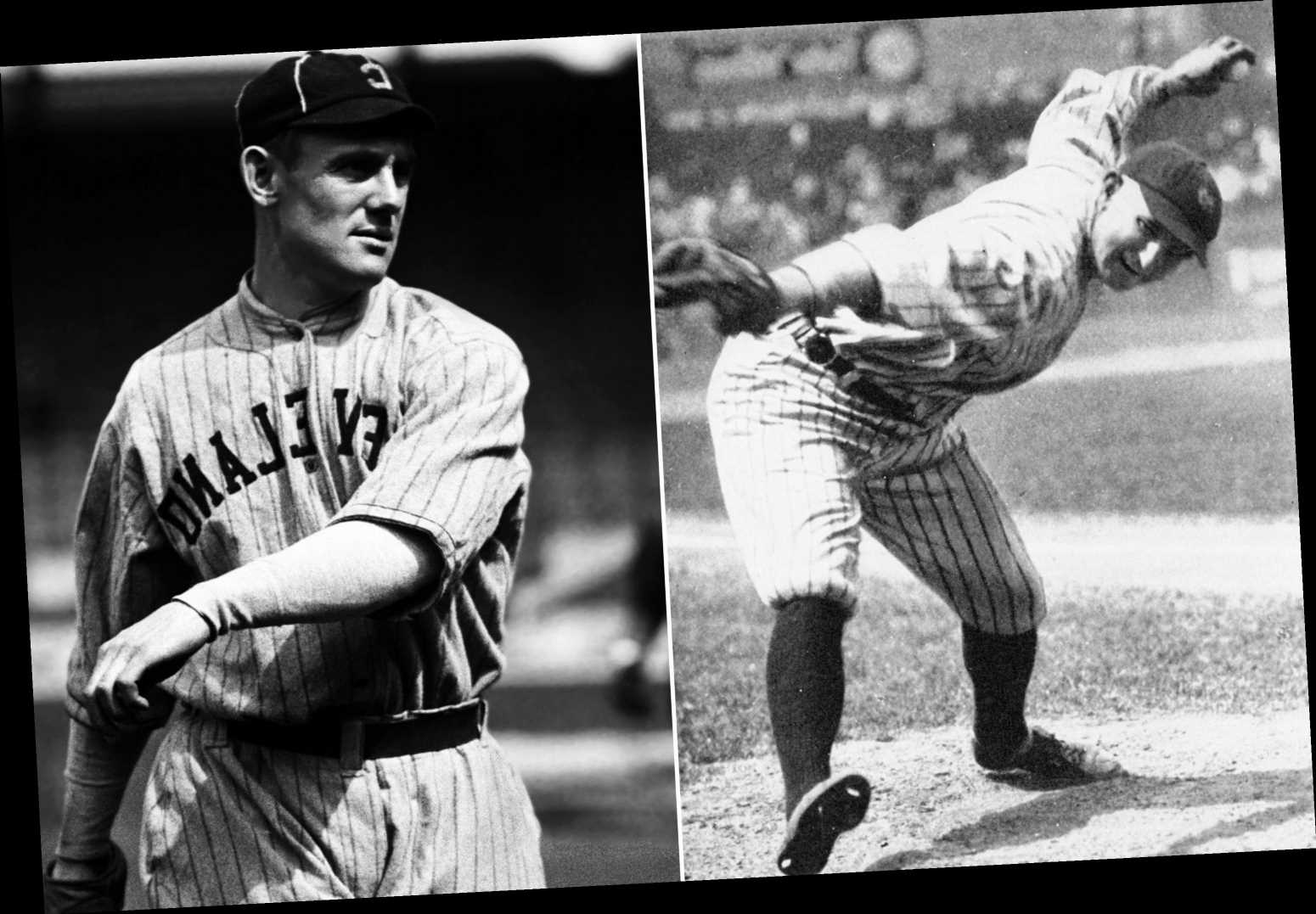

And so they did. The visiting Indians had taken the field in a virtual tie with the White Sox, just .004 percentage points behind Chicago. The Yankees were a half-game behind but had already made up four games in a week, and were throwing their ace, Carl Mays, a sidewinding righty seeking his 19th win.

The Tribe jumped on him, though, and led 3-0 through four innings thanks to their own ace, Stan Coveleski, who retired 12 of the 13 batters to face him, including Babe Ruth twice. Leading off the fifth was shortstop Ray Chapman, one of the most well-liked players in baseball, one of the most popular citizens in all of Cleveland.

That morning, a few of the Indians had taken the elevated train from the Ansonia Hotel at Broadway and 74th Street to Coogan’s Bluff, up on 155th. All of a sudden, Chapman began singing a song — “Dear Old Pal O’ Mine” — and soon his teammates joined Chapman’s distinctive tenor. After, noting that he’d had little success in his career against Mays, Chapman laughed.

“I’ll do the fielding today, boys,” he said. “You fellows do the hitting.”

He carried two bats with him to the plate now, nodded at Connolly, pulled his cap tighter, crouched slightly. Mays’ unorthodox delivery meant his knuckles practically scraped the mound as he reached his release point, but a fraction before he saw Chapman move ever so slightly. Chapman was the best bunter in the game. In that moment, mid-windup, Mays decided to alter his strategy from down-and-away to up-and-in.

That’s where the pitch went: high and tight. There was contact. Mays pounced, picked up the ball, threw to first baseman Wally Pipp for the out, and quickly shifted his focus to Tris Speaker, the Indians’ star and manager due up next.

But then Connolly yelled: “Time!”

And Mays turned and saw a terrible thing: Ray Chapman on the ground. Out cold. And then heard Connelly shouting again.

“We need a doctor!” he pleaded. “Is there a doctor in the house?!?”

Through the end of the 2019 season, there were 220,855 games played in the history of major league baseball. Hitters have come to the plate 15,106,184 times, and 111,521 hitters who were hit with pitched balls — some of them striking at 95 mph or higher. There were untold thousands of line drives struck, some hitting skulls and temples and throats at upwards of 110 mph.

There has been but one fatality. In a sense, that is baseball’s greatest miracle.

“It really is amazing,” says Mike Sowell — a longtime professor of journalism at Oklahoma State, a longtime sportswriter at the old Tulsa Tribune, and the author of “The Pitch That Killed,” the definitive book detailing the dreadful and fateful afternoon of Aug. 16, 1920 — 100 years ago Sunday. “And it makes you understand why hitters react the way they do when pitchers throw a hundred miles an hour in their eyes.”

There have been scares, plenty of them through the years. Boston’s Tony Conigliaro was one of baseball’s brightest stars until he was beaned by the Angels’ Jack Hamilton in August 1967. Dickie Thon was an All-Star shortstop for the Astros whose career was never the same after he was hit in the head by the Mets’ Mike Torrez in April 1984.

And pitchers are even more vulnerable to the whims of physics. Everyone who witnessed Masahiro Tanaka take a vicious line drive off the head on the Yankees’ first day of summer camp was shaken not only by the sickening thud, but the height the ball ricocheted after impact.

“That,” Sowell says, “is what the players on the field at the Polo Grounds talked about for years to come. The sound. They never forgot the sound. Even people in the stands, and it was crowded that day, remembered the sound.”

There were so many fateful twists and fatal turns that brought Mays and Chapman together in that awful moment. Consider, as beloved as Chapman was, Mays was equally disliked, even by teammates. He was a loner, not one to crush postgame beers with the boys. If an error was committed behind him, he wasn’t shy about showing his displeasure. He was known to scuff the ball, his favorite ploy scraping it against the rubber every time he picked it up to start an inning.

And he was known to pitch inside. Sometimes that resulted in hard feelings. Ty Cobb once asked him point blank if he threw at him on purpose, and Mays, being Mays, replied, “If you think so, that’s all that matters.” In 1917 — when he led baseball in HBPs, with 17 — Mays beaned Speaker on the very top of his head, and Speaker didn’t think that was an accident, either.

But back in the spring, Mays had been shaken when one of his few friends in the game, Yankees infielder Chick Fewster, had been beaned by Brooklyn’s Jeff Pfeiffer and knocked unconscious. He didn’t play again until July. Mays said, “When he was hurt by a pitched ball, it affected me so that I was afraid to pitch in close to a batter.”

And there was something else: Baseball’s owners had started to complain that the umpires were using too many balls, which cost $2.50 apiece in 1920. It was still common practice for teams to demand fans to return foul balls and home runs, and it irked them when umps would throw out balls that had been hardly dirtied.

So Ban Johnson, American League president, earlier that summer directed that umpires keep balls in play until they were on the brink of tatters.

Keep all of these things in mind as we return to the Polo Grounds 100 years ago, as we see Chapman slowly regaining his wits, rising to his feet, helped to the center field clubhouse by an army of mates. Harry Lunte replaced Chapman at first. Mays forged on. The Yankees staged a ninth-inning comeback, lost 4-3.

Afterward, at his locker, Mays was approached by a sportswriter named F.C. Lane of Baseball Magazine. Mays blamed his ineffectiveness on manager Miller Huggins moving him up a few days in the rotation. He mentioned that the ball was damp. Then he asked about Chapman.

“He was taken away in an ambulance,” Lane said. “That’s all I know.”

Mays placed his head in his hands, lost in thought.

In the clubhouse, Chapman had again begun to lapse. As he was hurried onto a stretcher, he asked the Indians’ secretary to retrieve his wedding ring from a safe. A team of doctors at St. Lawrence Hospital operated, removing a portion of his skull, relieving pressure on his brain. For a few hours, it seemed hopeful. But not for long.

At 4:40 a.m. on Aug. 17, Ray Chapman died. He was 29 years old, a lifetime .278 hitter but one of the best second basemen of his time. His wife, Kathy, pregnant with their daughter, arrived a few hours later and fainted upon hearing the news from his stricken teammates.

Mays was questioned by the district attorney but never charged. He expressed immediate remorse — “It was the most regrettable incident of my career, and I would give anything if I could undo what happened” — but he was also defiant in his conviction that this had been an accident, that his conscience was clear. If anything, he blamed Connolly for making him throw a wet, beaten-up ball; he was roundly vilified for that.

For a time there was talk of a league-wide boycott of Mays, of players refusing to play against him, but that dissipated. Mays wound up winning 26 games that year and 27 in 1921, and finished his career with a lifetime 207-126 record and a 2.92 ERA, and that compares awfully favorably to many of his contemporaries who made the Hall of Fame.

To his dying day in 1971 at age 79, he believed he knew why he was excluded.

“People blame me,” he told sportswriter Jack Murphy not long before he died. “But I know the truth. I sleep well at night.”

The Indians wandered in a funk for a time, but recovered to beat out the White Sox and Yankees for the pennant, then beat the Dodgers five games to two to win the best-of-nine World Series — the first world championship in Cleveland’s history. In one final twist one of the keys to that triumph was a rookie shortstop summoned from New Orleans to replace Chapman on the roster.

Joe Sewell went on to enjoy a Hall of Fame career with the Indians and the Yankees, and was the single-toughest man to strike out in baseball history (just 114 whiffs in 8,333 plate appearances). He was terrified when he was called up. But he calmed himself his first day in an Indians uniform, and for the rest of his life he explained why.

“I would forget I was Joe Sewell,” he said, “and imagine I was Ray Chapman, fighting to bring honor and glory to Cleveland.”

Helmets took a while

Following Chapman’s death in 1920, the 1921 Indians experimented with batting helmets made of leather, not unlike football helmets of the day, but quickly discarded then. The 1941 Brooklyn Dodgers and 1953 Pirates became the first teams to mandate plastic inserts for their players while batting, and a few other players — notably Phil Rizzuto — followed.

It wasn’t until 1956 when the National League required protection — either the inserts or complete helmets — for all its players, and in 1958 the American League followed suit. In 1971, MLB as a unit made it mandatory to use helmets, though it grandfathered players who wanted to stick with the inserts.

Boston’s Bob Montgomery, who retired in 1979, was the last MLB player to bat without a full helmet.

Share this article:

Source: Read Full Article