In 2018, more than 23 million people used dating apps — a number that’s expected to rise, according to Business Insider. It’s how many couples have met and even more people have planned dates. But these services have also required untold numbers of people to potentially give up valuable personal information, which companies can monetize and sell to third parties, effectively limiting users’ data privacy rights forever. As Shakespeare wrote in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, “The course of true love never did run smooth,” to which we posit: Yeah, but at what cost?!

“Whatever you put on the app, it’s not staying on the app,” Jo O’Reilly, a data privacy expert with advocacy group ProPrivacy, told MTV News. She added that many dating platforms collect everything from a user’s display name and location to their height, ethnicity, and swiping habits. The companies can then turn these details around to outside parties. “They’re using it to basically sell a profile of who you are to third-party advertisers.”

Companies can use the information they collect from users when they visit any website or dating app to target them with specific ads — a practice known as surveillance capitalism. And that doesn’t mean you’ll simply get more ads for beekeeping and cat toys — you can also be susceptible to manipulation. In 2016, the political consulting firm Cambridge Analytica collected personal data from Facebook users without their consent and used it as a “psychological warfare tool” to influence people’s votes ahead of the presidential election, according to Wired. Targeted ads can remind you to buy that shirt at Zara you can’t stop looking at, but they can also fan the flames of xenophobia. We simply don’t yet know the depths to which bad actors might use our data against us, or which data is most useful to a third party at any point in time.

“They can take all this information, and not just change your mind to buy something, but change how you think about the world and your political affiliations,” O’Reilly said. “Someone could use information about your weight and where you were shopping to sell you diet pills. There can be a real dark side to this.”

That dark side likely won’t keep people off the apps, though — according to an August 2019 MTV Insights study, 57 percent of respondents aged 18–29 said that dating apps made dating better overall. But 84 percent of respondents who identified as female and 60 percent of respondents who identified as male were also concerned about “stranger danger” they felt came with the territory of chatting with people they’ve never met in person. And given the number of headlines about app dates that have ended in offline dangers, people have plenty of reasons to be cautious of their matches. Experts warn, however, that they should also be wary of the apps themselves.

In early January, Grindr, OkCupid, and Tinder were at the center of a controversy in which researchers from the Norwegian Consumer Council accused the companies of breaking privacy laws to disclose personal information; at the time, each app denied the accusations. But the fact remains that users tell dating apps plenty of information about themselves, either through app-generated prompts or in DMs with matches and potential hookups. Those details can include a person’s preferred sexual positions, HIV status, religious beliefs, and political affiliation, all of which can ultimately be weaponized against someone. The privacy policy for Grindr, an app with four million users and a presence in 190 countries, states that it will share information with law enforcement if asked to do so, even in countries that criminalize homosexuality. (MTV News has reached out to the company for comment.)

“If there is a warrant, [Grindr] will disclose personal information in response to court orders,” O’Reilly said, cautioning that such compliance is a potentially “scary thing. They’ve never really clarified how far that would go. What does that mean to people that may be using the app anywhere where [LGBTQ+] relationships are still criminalized?”

Beyond the fear that dating apps are giving away personal data, people are often wary about how much they share about themselves, especially given that user data has surpassed oil in its value. But limiting the information you offer on these apps can often restrict the connections you make on them — and the dates you get as a result.

Julie Spira, an online dating coach and the author of The Perils of Cyber-Dating: Confessions of a Hopeful Romantic Looking for Love Online, told MTV News that your caution should even extend to your private messages, as companies can access those, too. Even so, there are ways to maintain your privacy rights without risking your social life.

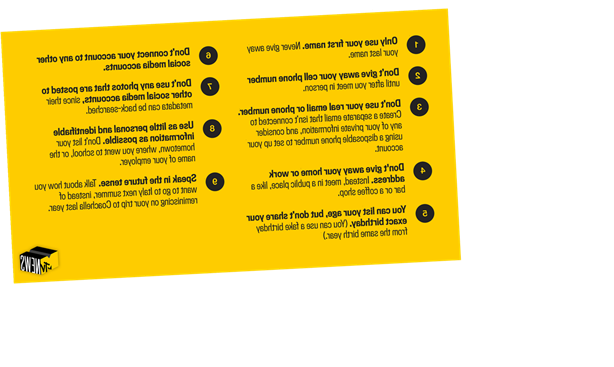

“You should ration your information flow,” Spira said. She recommends fudging your birthday; while “faking” your age can be a red flag for other users, you can add in a fake birthday during the same birth years as yours.

O’Reilly and Spira agreed that you should only ever use your first name, so leave your last name off the profile. They suggested creating an email that isn’t connected to any of your private information and using a disposable phone number to bypass the two-step authentication required to set up your account.

It’s always in your best interest to withhold giving someone crucial information, like your phone number, until after you’ve met IRL and decided you want to see this person again. Some apps like Burner help you create an intermediary number if you are negligent about checking your app’s unread messages, but it’s harder to report someone for indecent behavior if it doesn’t happen within the confines of a given platform.

As far as personal info, both O’Reilly and Spira recommended using as little personal and identifiable information on your profile as possible: Don’t list your hometown, where you went to school, or the name of your employer. And consider speaking in the future tense when navigating icebreakers and other small-talk. Talk about how you want to go to the Amalfi coast one day, rather than wax poetic about last year’s highly Instagrammed trip to Mexico City.

“It’s like peeling an onion one layer at a time because you are communicating with somebody that you don’t know, and you shouldn’t feel comfortable revealing your entire life,” Spira explained. “This isn’t like a history lesson or writing a novel. And so, it’s about being flirty and mysterious up to a point, but you still need to be able to connect.”

Overall, the best way to maintain privacy on dating apps is to change your approach altogether. You’re using them to get something specific out of the interaction, whether that’s validation, a date, a hookup, or love, but be mindful of the kind of rights you’re giving up to accomplish those goals.

That isn’t to say every precaution is airtight: Dating apps are rife with data breaches and people can take screenshots of your profile and tweet them out. It can be difficult to convince companies to erase data you gave of your own volition. But it’s always possible to adjust your habits, and taking control can feel empowering in the long run.

“I think it’s about using those apps to make the connections and then quickly taking it to a place where you can meet someone and get a real vibe for who they are in a more normal kind of real-world face-to-face setting, rather than spending kind of months messaging someone where you’re exchanging all kinds of personal details to someone that you haven’t actually met face-to-face,” O’Reilly said. Translation? Meet up for that date — ideally in a public place, with lots of people around.

And while there’s not much you can do in the United States to rescind the data you’ve already given away, there is a push to get a federal privacy law that will allow users to force companies to delete their personal information. O’Reilly stressed that potential legislation should include the right to be forgotten, a law in both the European Union and Argentina that gives users the right to have their private details removed from internet searches. U.S. courts don’t currently recognize this concept, but 88 percent of Americans support it, according to Forbes.

“There are a lot of laws coming into play that will, hopefully, as time goes on, make it easier to take back control of data that you’ve already put out there,” O’Reilly added. “But in the first place, we just have to try to be really careful about what we put about ourselves online.”

Source: Read Full Article