Pompeii: Archaeologists discover ceremonial chariot nearby

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

This week, researchers made a breakthrough discovery in Pompeii after finding the remains of a man believed to date back to the final decades before it was destroyed. It has been described as one of the best-preserved skeletons ever found at the ancient Roman city. Thought to be a former slave, a tomb inscription suggests the man helped to organise Greek performances, and also includes his name: Marcus Venerius.

It marks the first time archaeologists have found direct evidence of plays performed at Pompeii in Greek as well as in Latin.

The city, then, might once have been bustling with art and culture.

Yet, there is a darker side to the sprawling metropolis.

Like many regions in the Roman Empire, Pompeii was without a police force.

Citizens took justice into their own hands, determining what sorts of punishments to hand out to those caught committing crimes, and evidence suggests that in the years leading up to the volcanic eruption in 79 AD, crime was rife.

The Smithsonian Channel’s documentary, ‘Secrets: Gangs of Pompeii’, noted that the myraid relics found in the city not only capture scenes of everyday life, but also hint at “a city living in fear”.

Professor Rebecca Benefiel, a Roman historian from Washington and Lee University, said: “Theft is a problem because goods are portable, and it’s easy to walk off with them.

“And, especially if you think about the fact that there are no banks, and there would be no way to get it back.”

JUST IN: US rocked by mystery syndrome: Panic as officials report symptoms

Historical records tell us that for those on the lowest rungs of society, breaking the law was often their only chance of survival.

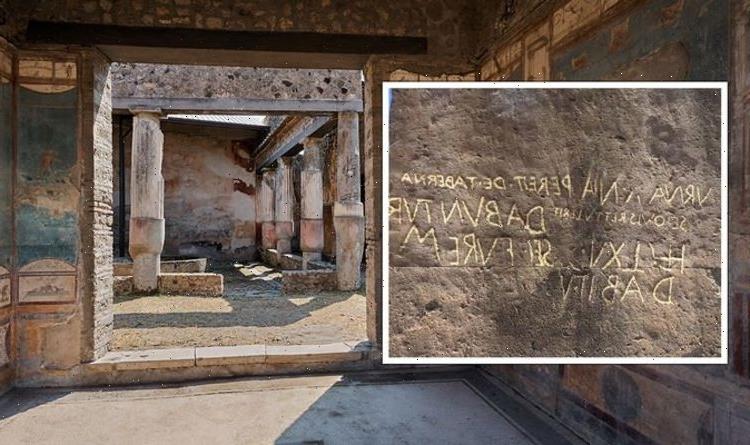

In the commercial heart of Pompeii, faint traces adorn the walls of how Romans took the law into their own hands.

Prof Bennefiel deciphered one message on the wall of an ancient tavern, where a bronze vessel had gone missing.

The proprietors sent a message to the city, asking for someone to bring the vessel back: “They will be given a reward of 65 sesterces”, it read, a lot of money at the time.

DON’T MISS

Kwarteng slams EU as Brexit Britain announces ‘world-leading’ plan [REPORT]

Archaeologists solve Arthur’s Stone origin mystery [INSIGHT]

Merkel’s plans skewered after warning UK ‘lags far behind’ Germany [ANALYSIS]

It also offered a bonus award in exchange for the thief.

The documentary said: “In a country with no police force and little state justice, residents were dishing out their own punishments.

“If apprehended, the thief who stole the bronze vessels could have faced untold suffering.

“Because for many Roman citizens, justice came in the form of vigilante punishment.”

The layout of a middle class home in the city provided ample evidence for who residents would rely on to carry out the rough justice.

A slave would control who visited the home, and could at times be “very scary”, the findings suggesting these slaves may have taken up extra work as vigilantes.

Gangs of citizens would also have formed to hunt down wanted people for a sum, “just like the family mafias in years to come”, the documentary noted.

But, today’s findings are a little less menacing.

Gabriel Zuchtriegel, director of Pompeii’s Archaeological Park who came across evidence for Greek performances, said: “That performances in Greek were organised is evidence of the lively and open cultural climate which characterised ancient Pompeii.”

Experts said the skeleton showed signs of partial mummification, with an ear and white hair still evident on the skull.

Source: Read Full Article