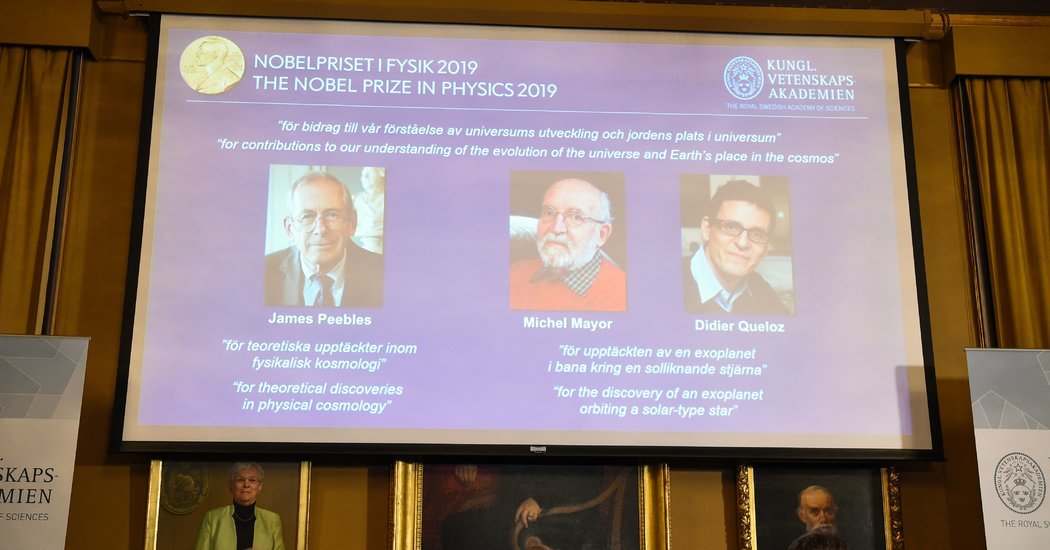

This year’s Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to three scientists who transformed our view of the cosmos, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced on Tuesday.

James Peebles, a professor emeritus at Princeton University, shared half of the prize — and half of the prize money of more than $900,000 — for theories that explained how the universe swirled into galaxies and everything we see in the night sky, and indeed much that we cannot see.

The other half was shared by two Swiss astronomers, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz, who were the first to discover an exoplanet, or a planet circling around a distant sun-like star.

“They really, sort of tell us something very essential — existential — about our place in the universe,” Ulf Danielsson, a member of the Nobel committee, said during an interview broadcast on the web.

Who are the winners?

James Peebles, the Albert Einstein professor of science at Princeton, was not entirely taken by surprise by the early morning phone call from Stockholm. “I have been working in cosmology for 55 years,” he said in an interview. “I’m the last man standing, so to speak, from those early days. It had crossed my mind.”

Michel Mayor is an astrophysicist and professor emeritus of astronomy at the University of Geneva. He formally retired in 2007, according to the Planetary Society, but remains active as a researcher at the Geneva Observatory.

Didier Queloz is a professor of physics at the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge University, and at the University of Geneva, where he works “at the origin of the exoplanet revolution in astrophysics.”

Why did they win?

In the 1960s, when Dr. Peebles began studying the cosmos, knowledge about the universe was sparse and imprecise. Astronomers had observed stars, galaxies, clouds of gas and other cosmic vistas through their telescopes, but struggled to explain much about them.

For example, cosmological distances were often just rough guesses, and estimates of the age of the universe varied widely.

Dr. Peebles’s work helped place cosmology on a more solid, mathematical foundation.

“No one has done more to establish our current paradigm than Jim,” Michael Turner of the University of Chicago and the Kavli Foundation, a philanthropy that supports science, wrote in an email.

In 1964, two radio astronomers, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, discovered by accident a background hiss of microwaves pervading the universe. They were perplexed until they came across theoretical calculations by other scientists including Dr. Peebles.

Dr. Peebles and his colleagues had predicted this background radiation, a result of when the universe, about 400,000 years after the Big Bang, cooled off enough for hydrogen and helium atoms to form.

While the microwave background was almost uniform in all directions, reflecting a temperature of only a few degrees above absolute zero, it was not perfectly smooth. Dr. Peebles calculated that there should be faint fluctuations, and the fluctuations would reveal the places where matter had begun to clump together — the structure that would eventually be revealed as stars, galaxies and clusters of galaxies.

In the early 1980s, Dr. Peebles became a proponent of the idea that the universe was filled with unseen “cold dark matter” — particles that did not interact with ordinary matter but whose gravitational pull formed galaxies and clusters of galaxies. A couple of years later, he added to his model a term that Albert Einstein had originally proposed then discarded as his “biggest blunder.”

[Read The Times obituary of Vera Rubin, who transformed physics with her work on dark matter.]

Einstein had invented this idea, called the cosmological constant, to balance gravity and keep the universe static and unchanging. But astronomers established that the universe is actually expanding. Dr. Peebles utilized the cosmological constant, now known as dark energy, for a different reason — he aimed to show that the universe contained considerably less mass than was thought at the time.

In 1998, two teams of astronomers discovered that Dr. Peebles was right and that the universe was not only expanding but accelerating.

“Jim has been involved in almost all of the major developments since the discovery of the cosmic microwave background in 1965 and has been the leader of the field for all that time,” Dr. Turner said.

Dr. Peebles noted that much of the universe remains mysterious. Scientists have yet to identify what makes up dark matter or dark energy.

The other half of this year’s Physics Nobel goes to research that filled in a missing piece of the observable universe.

Astronomers had long presumed there must be planets in orbits around many other stars. But until a quarter century ago, they knew of none. Over the decades, claims of spotting planets evaporated upon closer examination.

In 1992, astronomers found the first planets outside the solar system — but those orbited an exploded star, making them an unlikely place for life to exist.

At the time, some astronomers were beginning to wonder if they would ever find planets. “Maybe most stars don’t form with planets and our solar system is unusual and life is incredibly rare,” said Debra A. Fischer, a professor of astronomy at Yale.

Three years later at the Haute-Provence Observatory in southern France, Dr. Mayor and Dr. Queloz successfully found a planet around 51 Pegasus, a star similar to our sun, 50 light years away. It was as large as Jupiter, and hugged its star in an orbit that took only four days. Although this broiling planet was not habitable, it pointed to how astronomers could now study planetary systems that could be similar to our own.

“Completely transformative,” Dr. Fischer said of the discovery. “We are the middle a scientific revolution that people won’t appreciate until a hundred years go by.”

Dr. Mayor and Dr. Queloz did not see the planet directly. Rather, they looked at a periodic wobble in the colors of light from the star. The gravity of the planet pulled on the star. The motion back and forth shifted the wavelengths of the starlight, much like how whistle of a train or the siren on a police car rises when approaching and falls when receding.

Within months, other astronomers confirmed the discovery. For several years, skeptics wondered if the oscillations of starlight could be the result of pulsations of the star itself or the effect of a dim companion star. Then astronomers saw the dimming of starlight when a planet passed directly in front, and they found a star that had multiple planets in orbit around it.

“That laid to rest the concerns of at least 99 percent of the astronomers,” Dr. Fischer said.

More than 4,000 exoplanets have been discovered in our Milky Way galaxy since Dr. Mayor and Dr. Queloz announced their results, including some that may be habitable. More and more are being spotted with space telescopes like TESS, launched by NASA last year.

Who won the 2018 Nobel for physics?

The prize last year went to Arthur Ashkin of the United States, Gérard Mourou of France and Donna Strickland of Canada for their work with lasers and microscopy, developing tools such as optical tweezers and chirped pulse amplification.

Dr. Strickland was only the third woman to win the prize.

Who else has won a Nobel Prize this year?

The prize for medicine and physiology was awarded to William G. Kaelin Jr., Peter J. Ratcliffe and Gregg L. Semenza for their work in discovering how cells sense and adapt to oxygen availability.

When will the other Nobel Prizes be announced this year?

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry will be announced on Wednesday in Sweden. Read about last year’s winners, Frances H. Arnold, George P. Smith and Gregory P. Winter.

The 2018 and 2019 Nobel Prizes in Literature will be announced on Thursday in Sweden. The prize last year was postponed after the husband of an academy member was accused, and ultimately convicted, of rape — a crisis that led to the departure of several board members and required the intervention of the King of Sweden. Read about 2017’s winner, Kazuo Ishiguro.

The Nobel Peace Prize will be announced on Friday in Norway. Read about last year’s winners, Nadia Murad and Denis Mukwege.

The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Science will be announced on Monday in Sweden. Read about last year’s winners, William Nordhaus and Paul Romer.

Nobel Prize Winning Scientists Reflect on Nearly Sleeping Through the Life-Changing Call

How eight winners got the word.

___

Dennis Overbye contributed reporting.

Kenneth Chang has been at The Times since 2000, writing about physics, geology, chemistry, and the planets. Before becoming a science writer, he was a graduate student whose research involved the control of chaos. @kchangnyt

Megan Specia is a story editor on the International Desk, specializing in digital storytelling and breaking news. @meganspecia

Source: Read Full Article