Shipwreck in the middle of the Southern Irish Sea thought to be a submarine is identified as HMS Mercury – a minesweeper that sank on Christmas Day in 1940 after being damaged by a mine

- Researchers from Bangor University have been sonar scanning the Irish Sea

- Wrecks were compared to a list of lost ships from Bournemouth University

- HMS Mercury was identified based on the distinctive profile of her hull

- The paddle steamer, built in 1934, originally served as a passenger ferry

- However, she was requisitioned into the 11th Minesweeping Flotilla in 1939

Long thought to have been a submarine, a shipwreck in the middle of the Southern Irish Sea has finally been identified as the paddle steamer HMS Mercury.

Built in 1934, Mercury served passenger routes on the Firth of Clyde, Scotland, for five years before being requisitioned by the Admiralty as a minesweeper.

However, her military service was sadly short-lived, as the Mercury sunk on Christmas Day 1940 after being damaged by a mine she was attempting to clear.

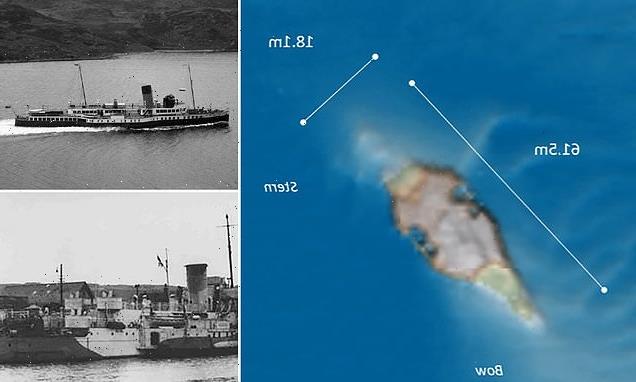

Experts at the universities of Bournemouth and Bangor identified the wreck from sonar images thanks to the distinct profile caused by her boxed-in paddle wheels.

Long thought to have been a submarine, a shipwreck in the middle of the Southern Irish Sea has finally been identified as the paddle steamer HMS Mercury, pictured here prior to 1940

Experts at the universities of Bournemouth and Bangor identified the wreck from sonar images thanks to the distinct profile caused by her boxed-in paddle wheels

One year into her military service, at 4.32pm on Christmas Day 1940, HMS Mercury was holed off the coast of the Saltee Islands by a mine exploding under her stern. The vessel stayed afloat for nearly five hours after the explosion, but took on too much water and sank as she was being towed across the sea towards Milford Haven

HMS MERCURY STATS

Type: Passenger steamer

Launched: January 16, 1934

Builders: Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering Company

Owners: London, Midland and Scottish Railway and the Caledonian Steam Packet Company

Cost: £46,000

Length: 229.5 feet

Beam: 30.0 feet

Tonnage: Gross 621

Max. speed: 17 knots

Capacity: 1,861 passengers

Features: Two restaurants, a tea room and a smoking bar (as a ferry), minesweeping gear (during wartime)

‘The wreck site was assumed to be the final resting place of a submarine,’ explained study leader and archaeologist Innes McCartney of Bournemouth University, who has been compiling a detailed list of all the vessels recorded lost in the Irish Sea.

‘Once the sonar data had been processed, the wreck resembled a paddle wheeled vessel with its paddles boxed into the vessel’s superstructure, rather than the characteristic tube-like profile associated with submarine wrecks.

‘Within our database of shipping losses there was only one possible candidate which featured boxed in paddle wheels — the minesweeper HMS Mercury.’

HMS Mercury, originally the ‘Mercury II’, was built in 1934 for the London, Midland and Scottish Railway, serving as an excursion vessel that primarily ran a route from Wemyss Bay to Gourock, Greenock, Dunoon and Rothesay in the Firth of Clyde.

The 223 feet-long paddle steamer — along with her sister-ship, the Caledonia II — was constructed with a number of then-innovative features, including both the aforementioned boxed-in paddle wheels and a cruiser stern.

One year into her military service, at 4.32pm on Christmas Day 1940, HMS Mercury was holed off the coast of the Saltee Islands by a mine exploding under her stern.

The explosive device — part of an older British minefield near the Coningbeg Light Vessel that was being cleared by the 11th Minesweeping Flotilla — got stuck in her sweeping gear and was being drawn too close as the crew tried to clear it.

The vessel stayed afloat for nearly five hours after the explosion, but took on too much water and sank as she was being towed across the sea towards Milford Haven.

All hands were rescued, but HMS Mercury’s commander, Temporary Lieutenant Bertrand Palmer, was court-martialled in 1941 and reprimanded for disobeying standing orders in stopping the ship when the mine was spotted trapped in the gear.

According to the 1940 Manual of Minesweeping, once a mine is spotted fouling the sweeping gear, the vessel should ‘go ahead at full speed and endeavour to part the mine moorings.’

Like HMS Mercury, the Caledonia II was also requisitioned by the navy during World War II, during which time it served under the name ‘HMS Goatfell’, first as a minesweeper and later as an anti-aircraft ship. Pictured: HMS Goatfell with her camouflage livery. While no photographs of HMS Mercury during the war appear to remain, she would have been similarly coloured

Like HMS Mercury, the HMS Goatfell (formerly Caledonia) spent the early part of her wartime service as part of the 11th Minesweeping Flotilla. Pictured: HMS Goatfell during the war

Like HMS Mercury, the Caledonia II was also requisitioned by the navy during World War II, during which time it served under the name ‘HMS Goatfell’, first as a minesweeper and later as an anti-aircraft ship.

Caledonia was returned to her owners — and passenger service — up in Clyde in 1946, where she remained in operation until 1969, when she was purchased by Bass Charrington breweries and converted into a floating pub and restaurant.

The ‘Old Caledonia’, as she was renamed, was moored on the Victoria Embankment on the Thames until 1980, when she was badly damaged by fire and scrapped.

Surviving the war, Caledonia was returned to her owners — and passenger service — up in Clyde in 1946, where she remained in operation (as pictured) until 1969, when she was purchased by Bass Charrington breweries and converted into a floating pub and restaurant

HMS Mercury is one of more than 300 shipwrecks in the Irish Sea surveyed using multi-beam sonar by Bangor University’s research vessel, Prince Madog.

‘This highly innovative research project has resulted in many discoveries dating from both world wars, of which HMS Mercury is just one example,’ said Dr McCartney.

Combining scientific surveys with maritime archives, he added, ‘can significantly enhance our understanding of the historic maritime environment by allowing us to identify unknown wrecks, refine existing attributes and confirm vessel identities.’

The ‘Old Caledonia’ (pictured) was moored as a floating pub and restaurant on the Victoria Embankment on the Thames until 1980, when she was badly damaged by fire and scrapped

‘Use of one of the most advanced multibeam sonar systems available has enabled us to very efficiently and accurately survey almost every wreck site in the central Irish Sea,’ agreed marine scientist Michael Roberts of Wales’ Bangor University.

‘These sunken vessels represent the sacrifices and efforts of citizens who were the “key” and “essential” workers of their time and it’s important that the final resting place of the vessels they were associated with are identified before it’s too late.

‘We hope to secure additional funding to expand on this work and examine wrecks in other UK coastal regions before their remnants become unidentifiable due to degradation through natural marine processes,’ he concluded.

HMS Mercury is one of more than 300 shipwrecks in the Irish Sea surveyed using multi-beam sonar by Bangor University’s research vessel, Prince Madog

SONAR EXPLAINED

Military equipment and animals that use sonar are simply making use of an echo.

When an animal or machine makes a noise, it sends sound waves into the environment around it.

Those waves bounce off nearby objects, and some of them reflect back to the object that made the noise.

It’s those reflected sound waves that you hear when your voice echoes back to you from a canyon.

Whales and specialised machines can use reflected waves to locate distant objects and sense their shape and movement.

Submarine sonars have been blamed for lethal mass stranding of deep diving toothed whales.

Sonar is thought to disrupt the animals’ diving behaviour so much that they suffer a condition rather like ‘the bends’ which human divers can contract if they surface too quickly.

Source: Read Full Article