Aztec manuscript dating back 500 years details 12 earthquakes from the 15th and 16 centuries and is the first written evidence of seismic activity in the Americas

- A 500-year-old manuscript found in Mexico is the first written evidence of earthquakes in the Americas

- It was created by Aztecs who used a type of writing known Codex Telleriano-Remensis, which is a pre-Hispanic system of symbols and colors

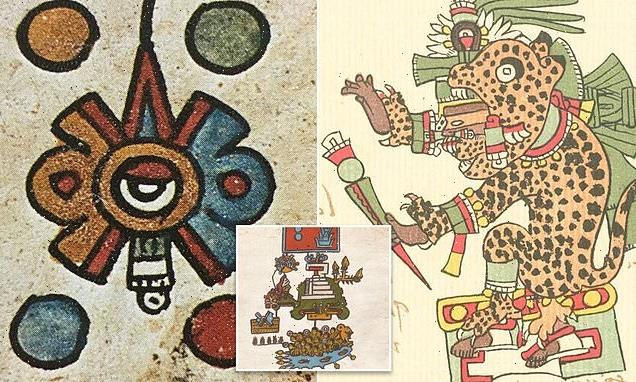

- Earthquakes, called tlalollin in the Nahuatl language, are represented by two signs: ollin (movement) and tlalli (earth)

- Ollin is a character consisting of four helices and a central eye or circle and Tlalli includes of one or several layers filled with dots and different colors

- The pictograms show natural phenomenoms and social events that happened when an earthquake hit

- This allowed experts to date the 12 earthquakes from 1460 and 1542

An Aztec manuscript from the 16th century that depicts the first written evidence of earthquakes in the Americas has been discovered in Mexico.

The manuscript highlights 12 earthquakes in Codex Telleriano-Remensis, a pre-Hispanic system of symbols and colors that was done by trained specialists called tlacuilos, which translates to ‘those who write paintings.’

The pictograms on the 500-year-old manuscript offer little information about the size, location and damages of each ‘quake, but historical accounts found in annals written after the Spanish conquest helped Mexican researchers determine the seismic events occurred between 1460 and 1542.

The images, however, also include natural phenomena and social events that occurred at the same time of an earthquake.

One pictogram, for example, shows an earthquake that hit in 1507, which happened the same time as a solar eclipse.

A temple was also destroyed during that year and 1,800 warriors drowned in a river that was likely in southern Mexico.

Scroll down for video

An Aztec manuscript from the 16th century that depicts the first written evidence of earthquakes in the Americas has been discovered in Mexico. Pictogram representing an earthquake that took place in 1507. The drowning of soldiers, a solar eclipse and a temple burning are also depicted

The manuscript was uncovered by Gerardo Suárez of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and Virginia García-Acosta of the Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social.

‘It is not surprising that pre-Hispanic records exist describing earthquakes for two reasons,’ Suárez said in a statement.

‘Earthquakes are frequent in this country and, secondly, earthquakes had a profound meaning in the cosmological view of the original inhabitants of what is now Mexico.’

Earthquakes, called tlalollin in the Nahuatl language, are represented by two signs: ollin (movement) and tlalli (earth).

Earthquakes, called tlalollin in the Nahuatl language, are represented by two signs: ollin (movement) and tlalli (earth). Ollin is a character consisting of four helices and a central eye or circle and Tlalli includes of one or several layers filled with dots and different colors

The manuscript highlights 12 earthquakes in Codex Telleriano-Remensis, a pre-Hispanic system of symbols and colors that was done by trained specialists called tlacuilos, which translates to ‘those who write painting.’ Picture is epeyollotl (‘heart of the mountains’) was the god of darkened caves, earthquakes, echoes and jaguars

Ollin is a character consisting of four helices and a central eye or circle and Tlalli includes one or several layers filled with dots and different colors.

In the Telleriano-Remensis, there are other modifications of the earthquake glyphs, but their meanings are not clear to scholars.

‘However, the consensus is that the various representations probably do have a meaning,’ Suárez said.

‘Drawing codices was a strict discipline not open to artistic whims of the people trained to do it, the tlacuilos.

‘We are hopeful that in the future an unknown codex or document may appear that may enlighten us in this respect.’

Pictured is a codex representation of an earthquake that took place in 1460. Below, the ollin glyph is embedded in the Earth represented as two layers

Suárez and García-Acosta note that other annals offer information that complements the earthquake drawings, perhaps filling in more details about the impacts and locations of specific earthquakes.

For example, a historical account by the Franciscan friar Juan de Torquemada describes a 1496 earthquake that shook three mountains in ‘Xochitepec province, along the coast’ and caused landslides in an area inhabited by the Yope people.

The site is within the Guerrero seismic gap, a region of relative seismic quiet along the subduction zone in southern Mexico.

The historical descriptions suggest that the 1496 earthquake might have been a very large earthquake with a magnitude 8.0 or larger within the gap.

There have been no recorded earthquakes of that magnitude in the gap since 1845.

The historical evidence ‘really does not change our view of the seismic potential of that region in southern Mexico,’ Suárez explained.

‘It simply adds additional evidence that great earthquakes have occurred in this segment of the subduction zone before, and the absence of these major earthquakes for several years should not be considered as though this region is aseismic.’

The Aztecs lived in Central Mexico from the 14th to the 16th centuries, and were famous for their agriculture, introducing irrigation, draining swamps and creating artificial islands in lakes. Their capital was Tenochtitlan on the shore of Lake Texcoco – the site of modern-day Mexico City

The Aztecs lived in Central Mexico from the 14th to the 16th centuries, and were famous for their agriculture, introducing irrigation, draining swamps and creating artificial islands in lakes.

They were also known for their cannibalism and human sacrificial rituals.

Their capital, Tenochtitlan, was on the shore of Lake Texcoco – the site of modern-day Mexico City.

Many of the temples and pyramids they constructed are still standing today. They include those at El Tepozteco in the Mexican state of Morelos and Acatitlan in the town of Santa Cecilia.

Source: Read Full Article