Tree-mendous recovery: Elm trees are making a comeback in Britain thanks to the development of new breeds that is resistant to Dutch elm disease

- Dutch elm disease is a devastating and widespread fungus spread by beetles

- The fungi is thought to have originated in Asia, arriving in Europe around 1910

- Between 1960–1970 an outbreak killed 25 million trees across southern Britain

- However a report from the Future Trees Trust suggests the elm is recovering

Elm trees are making a comeback in Britain thanks to conservation efforts and the development of new breeds that are resistant to Dutch elm disease.

The fungal condition that is spread by beetles and causes wilting and dead leaves killed around 25 million trees in southern Britain between 1960–1970.

However, research into disease resistant strains appears to be paying off, a recently-released report form the Future Trees Trust has noted.

Scroll down for video

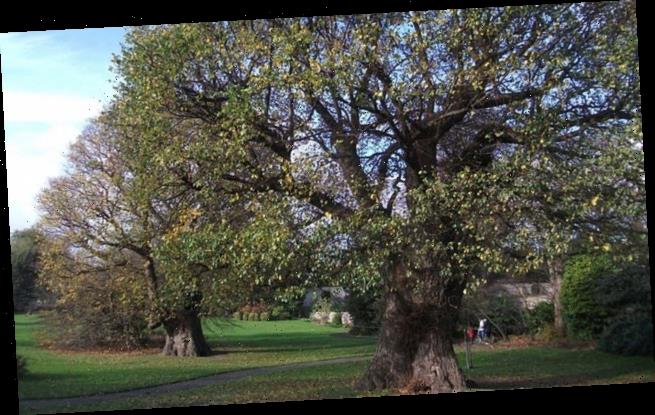

Elm trees are making a comeback in Britain thanks to conservation efforts and the development of new breeds that are resistant to Dutch elm disease. Pictured, the world’s oldest elm trees — known as the Preston twins — in Brighton’s Coronation Garden, seen here before one of the pair became infected with Dutch elm disease. Both were planted around 1613

WHAT IS DUTCH ELM DISEASE?

Dutch elm disease — named after the nationality of its discoverers — is a harmful condition caused by a type of sac fungi thought native to Asia.

The affliction causes leaves to wilt and die off, generates discolouration in both spring and autumn and also causes young shoots to wither.

Spread by elm bark beetles, the disease was introduced to Europe around the year 1910, subsequent to which it has devastated the native elm numbers.

When the fungus swept across southern Britain in the sixties and seventies, it killed around 25 million trees — over 90 per cent of the elm population.

The report was commissioned by the Futures Trees Trust and prepared by woodland management consultant Karen Russell.

She gathered information concerning elm usage, breeding, population locations and plant collections.

‘In undertaking this project, it has become very apparent to me that elm, as a tree and for its timber, is held in great regard,’ said report author Karen Russell.

‘It was our second most important timber broadleaf tree after oak. Elm still supports a wide range of biodiversity.’

‘By working together to promote the use of elm, and to understand why some trees are able to avoid or resist Dutch Elm Disease, private individuals and organisations now have a great opportunity to enable the return of elm to our countryside.’

‘The current state is that we know a lot about where the mature trees are and we know more than we’ve ever done about the opportunities in terms of research possibilities,’ Ms Russell told the BBC.

‘With the right people in the right place and the funding we can put elm back in the landscape,’ she added.

To determine future conservation opportunities, Ms Russel consulted with various relevant organisations and individuals, including the Conservation Foundation, the Woodland Trust, the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew and Forest Research.

Dutch elm disease is a fungal condition that is spread by beetles and causes wilting and dead leaves killed around 25 million trees in southern Britain between 1960–1970. Pictured, a rare elm tree in Sheffield which was under threat from local council plans to cut it down

Dutch elm disease — named after the nationality of its discoverers — is a harmful tree condition caused by a type of sac fungi thought native to Asia.

The affliction causes leaves to wilt and die off, generates discolouration in both spring and autumn and also causes young shoots to wither.

Spread by elm bark beetles, the disease was introduced to Europe around the year 1910, subsequent to which it has devastated the native elm numbers.

When the fungus swept across southern Britain in the sixties and seventies, it killed around 25 million trees — over 90 per cent of the elm population.

Research into Dutch elm disease resistant strains appears to be paying off, a recently-released report form the Future Trees Trust has noted. Pictured, such developments were sadly too late to save one member of the Preston twins, which contracted the disease earlier this year

Today, the fungus is still present in the British countryside and is spreading northwards — although it has yet to reach some parts of Scotland.

Young elms can still be seen growing in hedgerows — only to die from the disease before they are able to grow to maturity. Meanwhile, a handful of surviving trees exist across Britain — such as in Brighton and Cambridgeshire.

It is unclear how these ancient stalwarts, some of which are hundreds of years old, have managed to survive. This is something researchers are keen to determine.

Restoring the elm requires the cultivation of a new generation of trees that is resistant to the disease — with some progress having been mad in cross-breeding such hardy strains with local elm varieties for this purpose.

The affliction causes leaves to wilt and die off, generates discolouration in both spring and autumn and also causes young shoots to wither. Pictured, an infected elm tree is felled in Bruntsfield Links, Edinburgh to contain the spread of the disease

The development of young elms is ‘looking promising’, despite still being in the early stages, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh botanist Max Coleman told the BBC.

The return of elm trees to the British countryside will be good news for the lichen who live on both their bark and that of ash trees — the latter of which having been perishing at the hands of so-called ash dieback infections.

‘These specialised fungi are running out of habitat as suitable trees disappear from the landscape,’ he added.

‘Planting a new generation of elms that are likely to grow to maturity will help to provide new habitat for this important and overlooked group of fungi.’

The development of young elms is ‘looking promising’, despite still being in the early stages, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh botanist Max Coleman told the BBC

‘It’s clear that there’s a lot of love for elm and our report shows that there’s much to be hopeful about,’ said Future Trees Trust CEO Tim Rowland.

‘We now need to work together with all the other stakeholders to ensure the brightest possible hope for the return of this iconic species to our countryside.’

The full findings of the report were published on the Future Trees Trust website.

Source: Read Full Article