- The Ridgecrest earthquakes that struck Southern California last July may have increased the chances of a large quake along the San Andreas fault, new research shows.

- The San Andreas fault line runs through 800 miles of the California coast. A major earthquake — referred to as "the big one" — would devastate Los Angeles and other cities.

- The chances of such a disaster are still low, but the researcher who calculated them wants residents to be prepared.

- Visit Business Insider's homepage for more stories.

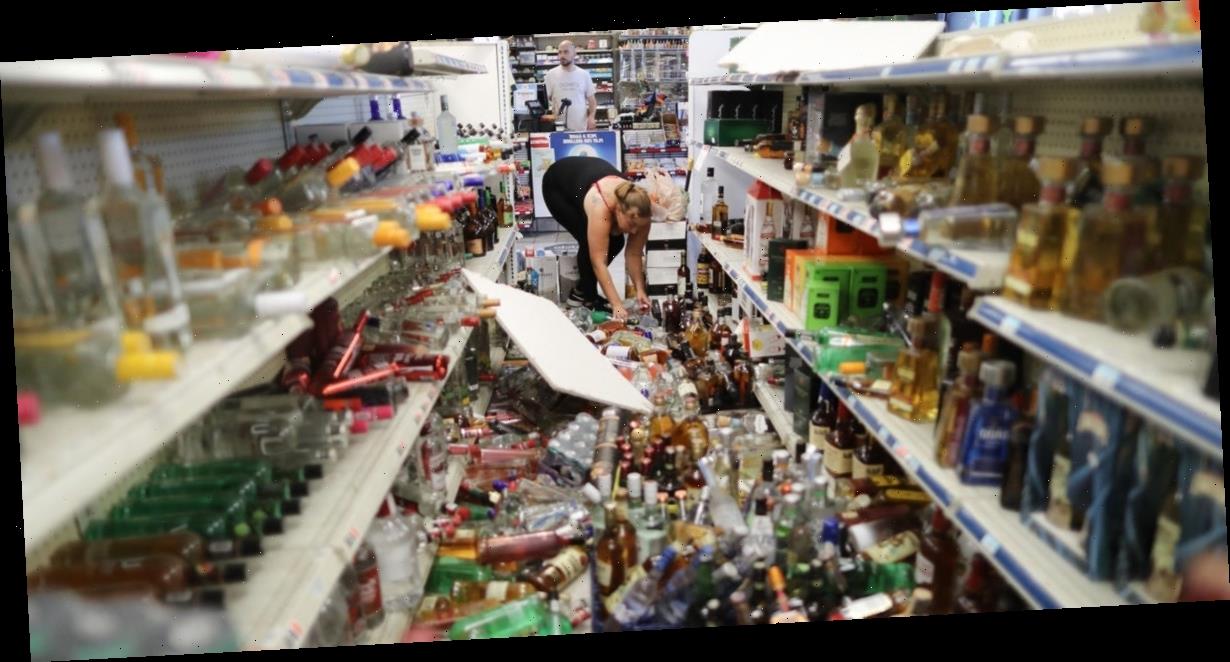

This time last year, a series of powerful earthquakes struck Southern California, culminating in a 7.1-magnitude temblor and a set of aftershocks. Buildings caught fire. Gas lines ruptured, and power went out. Deep fissures opened in the ground. A rockslide blocked off a highway.

Within less than a week, scientists recorded more than 3,000 quakes in the area around California's Searles Valley.

Those tremors may have inched the state closer to a much larger, deadlier catastrophe.

That's because the series of seismic events — dubbed the "Ridgecrest earthquakes" for the town near their epicenter — increased the chances of a large rupture on the San Andreas fault, according to two seismology researchers.

The San Andreas slices through 800 miles of the California coastline, from Eureka to San Bernardino. The fault long overdue for "the big one" — the term for a magnitude 6.7 or higher along that fault.

The big one will likely crumble buildings, cause explosions from ruptured natural gas lines, trigger landslides, and collapse bridges. The new research suggests that smaller earthquakes in California could trigger such a disaster via connecting fault lines.

A connecting fault line could have triggered 'the big one'

The new threat comes by way of the Garlock fault line, which runs 160 miles through the Mojave Desert and connects the site of the Ridgecrest quakes to the larger San Andreas fault. The Garlock fault previously had an estimated 0.023% chance of producing an earthquake of magnitude 7.5 or greater in the next 12 months. But after Ridgecrest, the researchers calculated that those odds grew to 2.3% — a 100-fold increase.

If such an earthquake were to strike the Garlock fault, it could trigger a disaster along the San Andreas. That means there is a 1.12% chance of a large earthquake on the San Andreas within the year. That's about three to five times more likely than in a normal year, according to the study.

"The Ridgecrest earthquake brought the Garlock fault closer to rupture. If that fault ruptures — and it gets within about 25 miles of the San Andreas — then there's a high likelihood, maybe a 50/50 shot, that it would immediately rupture on the San Andreas," Ross Stein, an author of the study and formerly a geophysicist at the US Geological Survey, told the Los Angeles Times.

Stein is also the CEO of Temblor, a catastrophe-modeling company. His study co-author, Shinji Toda, is a seismologist at the International Research Institute of Disaster Science at Tohoku University in Japan. Their findings are set to be published Tuesday in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

However, the chances of a major San Andreas earthquake in the next year remain low.

"It's kind of a Rube Goldberg scenario," Susan Hough, a USGS research seismologist told The New York Times of the scenario that Stein and Toda describe. "It's possible, but in terms of something to worry about, it's a low probability."

Still, seismologists agree that the big one is overdue.

"The last big earthquake to hit the LA segment of the San Andreas fault was 1680," physicist Michio Kaku told CBS News last July. "That's over 300 years ago. But the cycle time for breaks and earthquakes on the San Andreas fault is 130 years, so we are way overdue."

Stein emphasized the importance of being prepared: stocking up on water, nonperishable food, and emergency medical supplies, as well as knowing what to do in the event of a major earthquake.

"Nobody should panic," he told the Times. "But at the same time, the inference that the San Andreas likelihood of rupture has increased should be a reminder that anybody in Los Angeles should ask themselves, 'Am I ready?'"

Source: Read Full Article