The failure of Nazi Germany’s nuclear program is well established in the historical record. What is less documented is how a handful of uranium cubes, possibly produced by the Nazis, ended up at laboratories in the United States.

Scientists at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and the University of Maryland are working to determine whether three uranium cubes they have in their possession were produced by Germany’s failed nuclear program during World War II.

The answer could lead to more questions, such as whether the Nazis might have had enough uranium to create a critical reaction. And, if the Nazis had been successful in building an atomic bomb, what would that have meant for the war?

Researchers at the laboratory believe they may know the origins of the cubes by the end of October. For the moment, the main evidence is anecdotal, in the form of stories passed down from other scientists, according to Jon Schwantes, the project’s principal investigator.

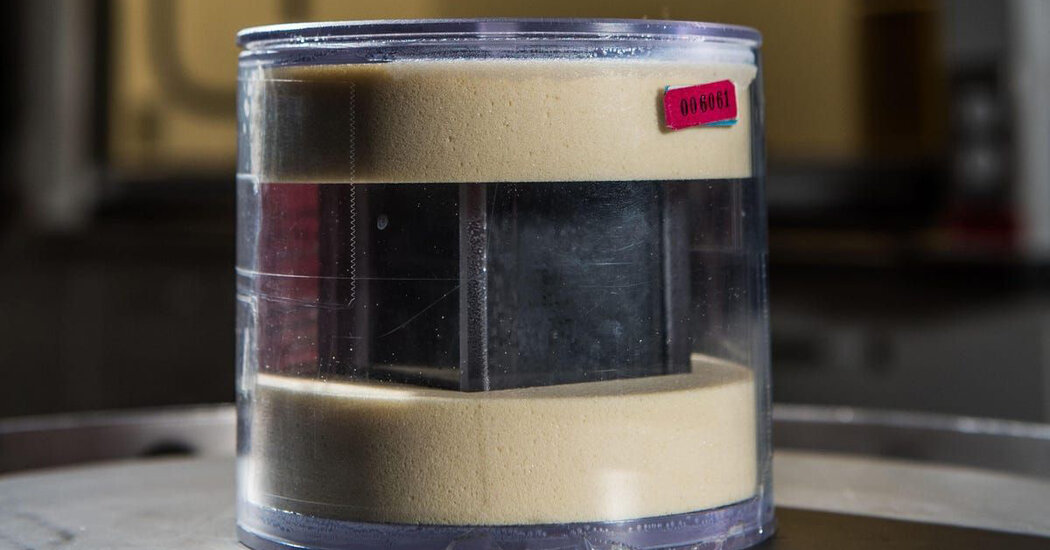

The lab does not have scientific evidence or documentation that would confirm that Nazi Germany produced the black cubes, which measure about two inches on each side. The Nazis produced 1,000 to 1,200 cubes, about half of which were confiscated by the Allied forces, he said.

“The whereabouts of most all of those cubes is unknown today,” Dr. Schwantes said, adding that “most likely those cubes were folded into our weapons stockpile.”

“The crux of our effort is to first and foremost confirm the pedigree of these cubes,” he said. “We do believe they are from Nazi Germany’s nuclear program, but to have scientific evidence of that is really what we’re attempting to do.”

When they were first produced, the cubes were essentially pure uranium metal. Over time, that elemental uranium has partly decayed into thorium and protactinium. To determine the age of the cubes, researchers plan to use a process called radiochronometry, which can separate and quantify the cubes’ chemical makeup.

“Uranium decays at a regular rate,” Dr. Schwantes said. “So when we measure the ratio of thorium to uranium in the cube, that is essentially a measure of the amount of time that has passed.”

And fixing a time when the cubes were made would help in tracing whether it could have been in the early 1940s in Germany. Such a determination would also bring more questions: Could the Nazis have built their own bomb, lengthening the war or even changing the outcome?

Ultimately, German forces were defeated by the Allies in May 1945, ending the war in Europe, and in the Pacific, Japan held on until September, surrendering only after the United States dropped atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing tens of thousands of people.

Dr. Schwantes, who said he gravitated toward math and chemistry in school, said he preferred not to speculate about how history could have been different, but said it was surreal to “hold this kind of historic material in hand and think about where it’s been, and who else has held it.”

Some historians think that even with nuclear capability, the Nazis would not have been able to change how the war ended.

Kate Brown, who teaches environmental and Cold War history at M.I.T., speculated that Nazi Germany’s production of nuclear weapons probably wouldn’t have had much of an impact on the war.

“They were in total war mode, increasingly so,” she said. “They could have made a dirty bomb. That’s not as difficult as making a nuclear bomb.”

A key ingredient the Germans needed to produce an atomic bomb was heavy water, which is water made of a hydrogen isotope called deuterium that has twice the mass of regular hydrogen.

In their quest to produce an atomic bomb, the Germans wanted to use a method in which uranium is submerged in heavy water, Professor Brown said. But the Allies dealt those plans “a big blow” when they bombed a plant in Norway that was the only place the Germans could get the key ingredient, she added.

Additionally, to succeed in its efforts, Nazi Germany would have needed large factories to produce bombs, vast tracts of land to test them and security from the threat of aerial attacks so that enemies could not spy on them, Professor Brown said.

Adam Seipp, a history professor at Texas A&M University, said Nazi Germany lacked the resources because it was “really bad at industrial production.”

“It’s one of the reasons they lost the war so catastrophically,” he said.

Professor Brown said that even if Nazi Germany had been able to produce a dirty bomb, the Germans would have needed a plane that could fly undetected for a long distance.

“They wouldn’t have had planes that could have reached cities like Moscow,” she said. “Really, the only target I can think of would be London,” she said.

Professor Brown said that while a Nazi bomb would not have had much of an impact on the war, the Nazis set the stage for the Cold War simply by trying to build one. The Soviets, who were then U.S. allies in defeating Germany, were aware that the Americans took this uranium out of the country “right out from under them,” she said.

“That becomes a real engine for suspicion that sets up the Cold War, almost immediately,” Professor Brown said.

After the war, the Soviet Union and the United States were both interested in German scientists and their equipment, Professor Seipp said. The United States even launched a covert effort, Operation Paperclip, with the objective of “moving high-value German scientists to the United States, and often, frankly, ignoring their very problematic wartime pasts, so that they stay out of Soviet hats.”

“That helps to kind of widen the growing gap between these former allies,” he said.

What ensued was an arms race between the United States and the Soviets (the U.S. showed its strength first when it bombed Japan in 1945), which was followed by a space race between the former allies.

For now, Dr. Schwantes said preliminary results on two cubes look promising. The science being used to date the cubes is not new, he said, adding that radiochronometry is the same technique scientists used to establish the age of the earth as 4.5 billion years.

“In our case, it’s the same science applied to different problems,” Mr. Schwantes said. While the scientists who established Earth’s age were working with time scales in the billions of years, he said, “We’re interested in time regimes that are like zero to 100 years.”

Source: Read Full Article