The bones shed new light on the history of the Crusades.

(Claude Doumet-Serhal)

A medieval burial pit in Lebanon is shedding new light on the Crusader era in the Middle East.

The Crusades were a series of religious wars that began in the 11th century and lasted until the 13th century when the Christian crusaders were forced out of their last strongholds in what is now Israel and Lebanon.

Scientists studied the DNA of nine Crusaders buried in a 13th-century burial pit near a crusader castle close to the Lebanese city of Sidon. The study, which is published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, found that the Crusaders were genetically diverse and that they had children with the local population.

Three of the crusaders were European, four were Near Easterners and two had mixed ancestry, according to the researchers.

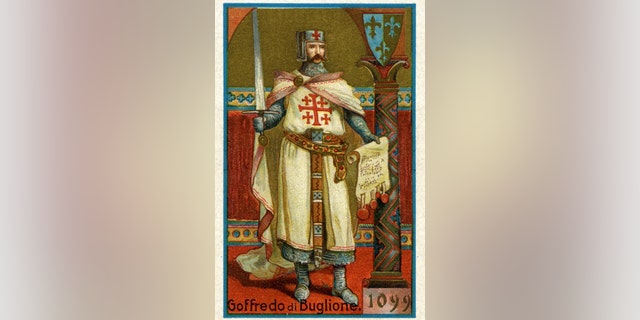

Chromo illustration (from the Liebig figurine series) of Duke of Lower Lorraine, Goffredo di Buglione (1061 – 1100), Italy, circa 1900. As Goffredo III (between 1089 – 1100), he participated in the first Crusade (1096 – 1099).

(Photo by Fototeca Gilardi/Getty Images)

"Our findings give us an unprecedented view of the ancestry of the people who fought in the Crusader army. And it wasn't just Europeans," said the study’s first authorMarc Haber of the U.K.’s Wellcome Sanger Institute, in a statement. "We see this exceptional genetic diversity in the Near East during medieval times, with Europeans, Near Easterners, and mixed individuals fighting in the Crusades and living and dying side by side."

"We know that Richard the Lionheart went to fight in the Crusades, but we don't know much about the ordinary soldiers who lived and died there, and these ancient samples give us insights into that," said Chris Tyler-Smith, a genetics researcher at the Wellcome Sanger Institute and the study’s senior author.

However, traces of Crusader DNA are “insignificant” among modern Lebanese people. The researchers noted that other mass migrations, such as the Spanish and Portuguese colonization of South America, have impacted the genetic makeup of those regions.

The Crusader bones found in the 13th-century burial pit.

(Claude Doumet-Serhal)

In contrast, the Crusaders’ relatively short-lived presence in the Middle East, has had less of a genetic impact. "They made big efforts to expel them, and succeeded after a couple of hundred years," said Tyler-Smith.

The scientists found that the DNA of modern Lebanese people has more in common with people living in the region when it was part of the Roman Empire 2,000 years ago.

Other stunning Crusader-era discoveries have been garnering attention recently. The room venerated as the site of Jesus’ Last Supper, for example, has been revealed in stunning detail thanks to remarkable 3D laser scanning technology. The Cenacle is part of a church built by the Crusaders over an earlier 4th-century Byzantine church.

The bones highlight the Crusaders’ genetic diversity.

(Claude Doumet-Serhal)

Last year, experts discovered a Gothic hall at a medieval Crusader fortress in northern Israel. The ceremonial hall found in Galilee's Montfort Castle offers a fascinating glimpse into the turbulent Crusader era in the Holy Land, which began in the 11th century and lasted until the 13th century.

In 2017, amazing medieval jewelry was found during the excavation of a Crusader castle on Tittora Hill in the town of Modi’in-Maccabim-Re’ut.

In 2016, a centuries-old hand grenade that may date back to the time of the Crusaders was among a host of treasures retrieved from the sea in Israel. The hand grenade was a common weapon in Israel during the Crusader era.

Over decades, archaeologists have also uncovered the ruins of the once-thriving Crusader city in the modern Israeli city of Acre.

Follow James Rogers on Twitter @jamesjrogers

Source: Read Full Article