Last month, a Chinese spacecraft left Earth on a mission to collect rocks and soil from the moon. On Wednesday, that mission, Chang’e-5, is to return a capsule to our planet. If it succeeds, it will be the first new cache of lunar samples for scientists to study since 1976, and proof that China is not only capable of going beyond Earth, but also of bringing something back.

When will the moon rocks arrive on Earth, and how can I follow it?

The moon rocks will touch down in Inner Mongolia, a Chinese region, around 1 p.m. Eastern time (it will be very early on Thursday in China), according to James W. Head III, a planetary scientist who collaborated with Chinese scientists who helped choose the landing site.

China’s space agency has not yet announced any coverage of the return and recovery of the capsule. The country has often waited until after a space mission is successful to announce results. But it has been more open and transparent with the Chang’e-5 mission to the moon, including a live broadcast of the launch, potentially a sign of growing confidence in its space program.

Where did China’s moon rocks come from?

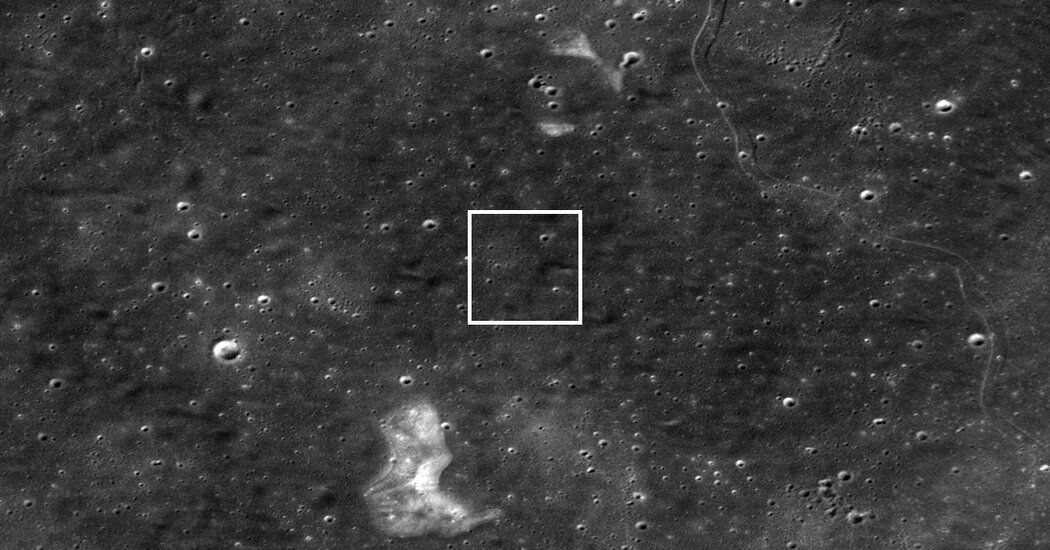

The Chang’e-5 moon lander went to a volcanic plain called Mons Rümker in the Oceanus Procellarum region on the moon’s near side. The Chinese picked this site aiming to better understand a much younger part of the moon. While the United States and Soviet Union brought back moon rocks during the Apollo and Luna missions in the 1960s and ’70s, the sites they visited were all more than three billion years old. Mons Rümker is estimated to be 1.2 billion years old.

With younger moon rocks, planetary scientists on Earth can better calibrate techniques for estimating the ages of geological surfaces on planets, moons and asteroids throughout the solar system. The specimens may also help scientists test hypotheses about what caused the volcanism in that part of the moon when the rest of the body had quieted down.

What has China’s spacecraft done since it left Earth?

The Chang’e-5 mission required feats of engineering and execution that China had never attempted before, rivaling some of what NASA, the European Space Agency and the Soviet Union have accomplished.

Not long after arriving in lunar orbit, Chang’e-5 split into two parts, an orbiter and a landing craft. The orbiter continued to circle the moon while the lander headed to the surface on Dec. 1, becoming the third Chinese mission to touch down on the moon successfully. (The others, Chang’e-3 and Chang’e-4, are still in working order. Chang’e-4 is the only spacecraft from Earth to set down on the moon’s far side.)

On the lunar surface, the lander deployed its tool set, drilling for samples and scooping as many as 4.4 pounds of them into a container that would come back to Earth. The spacecraft also raised a small Chinese flag.

By Dec. 3, the container was tucked away, and the ascent part of the lander then fired its rocket and headed back to lunar orbit. That was the first Chinese mission ever to blast off from another world.

It met the spacecraft that had stayed in lunar orbit, docking to transfer the sample to the capsule that is to parachute to Earth. The portion that lifted off from the moon soon detached, making a controlled crash on the moon’s surface, presumably allowing China’s space program to gather more data in the process.

The remaining spacecraft, laden with lunar samples, then started its return to Earth, steadily expanding its orbit until it could easily transfer to a trajectory back to Earth, culminating with the drop-off of the capsule on Wednesday.

What will happen once the moon samples arrive in China?

The samples will be carefully prepared to prevent contamination. Chinese space officials say both Chinese and foreign scientists will have an opportunity to study the rocks and soil, but final procedures are still being determined.

American scientists may be left out because of restrictions imposed by Congress that have limited direct interactions between NASA and the Chinese since 2011. Those restrictions do not directly affect non-NASA scientists, but they prevent Chinese scientists from studying NASA’s Apollo rocks, and thus China may not wish to share its lunar samples with scientists in the United States.

What other rocks from space have come back to Earth recently?

China isn’t the only country to bring something back from space in December.

On Dec. 5, a Japanese spacecraft, Hayabusa2, returned to Earth after a round-trip journey of billions of miles that lasted six years. It had been collecting samples form Ryugu, a near-Earth asteroid, and ejected them into the Australian outback, where a Japanese crew retrieved them the next day.

On Tuesday, JAXA, the Japanese space agency, confirmed that the mission had returned to Earth with a “large number of particles,” showing rocks inside a canister that almost had the appearance of clumped coffee grounds. Scientists will use the asteroid samples to understand the composition of the rocks that were the building blocks of the solar system’s inner planets, including Earth.

Exploring the Solar System

A guide to the spacecraft beyond Earth’s orbit.

Sync your calendar with the solar system

Never miss an eclipse, a meteor shower, a rocket launch or any other astronomical and space event that's out of this world.

Source: Read Full Article