Most of the world maps you’ve seen in your life are past their prime. The Mercator was devised by a Flemish cartographer in 1569. The Winkel Tripel, the map style favored by National Geographic, dates to 1921. And the Dymaxion map, hyped by the architect Buckminster Fuller, debuted in a 1943 issue of Life.

Enter a brash new world map vying for global domination. Like sports, the mapmaking game can sometimes grow stale when top competitors are stuck on the same old strategy, said J. Richard Gott, an astrophysicist at Princeton who had previously mapped the entire universe. But then along comes an innovator: Think Stephen Curry of the Golden State Warriors, splashing 3-pointers from areas of the court the rest of basketball hadn’t thought were worth guarding.

“We were sort of reaching the limit of what you could do,” Dr. Gott said. “If you wanted any significant breakthrough, you had to use a new idea.”

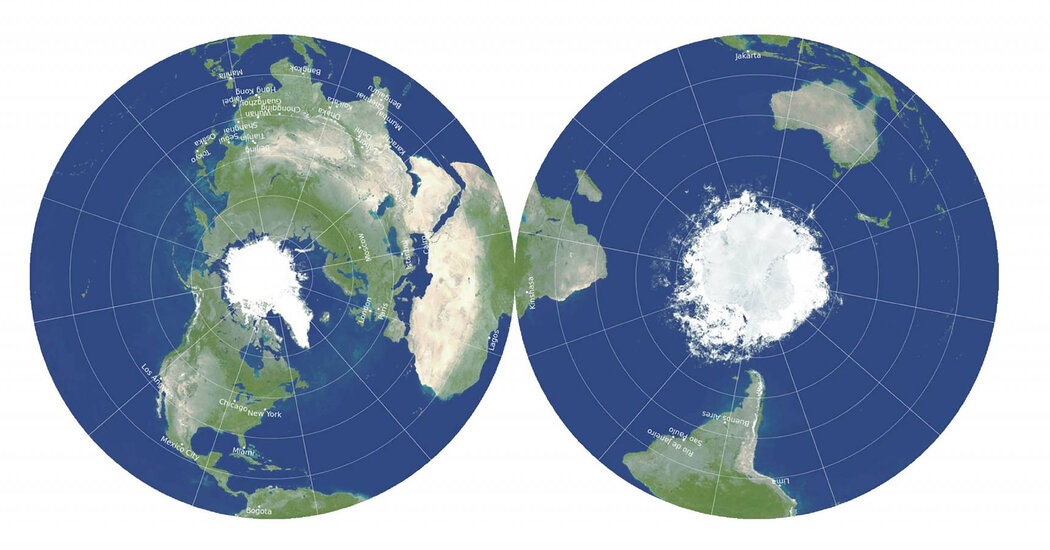

Dr. Gott’s version of Steph Curry’s wait-you-could-shoot-from-there 3? Use the back of the page, too. Make the world map a double-sided circle, like a vinyl record. You could put the Northern Hemisphere on the top side, and the Southern Hemisphere on the bottom, or vice versa. Or to put it differently: You could deflate the 3-D Earth into two dimensions. And if you did, you could blow the accuracy of previous maps out of the water.

No flat map of our round world can be perfect, of course. First you need to peel off Earth’s skin, then pin it down. This mathematical taxidermy introduces distortions. If you have a Mercator projection on your classroom walls, for example, you may grow up thinking Greenland is the size of Africa (not even close) or Alaska looms larger than Mexico (also nope). This warped worldview might even bias you, subconsciously, to under-appraise most of the developing world.

Shapes also change in map projections. Distances vary. Straight lines curve. Some projections, such as Mercator, aim to excel at one of these concerns, which aggravates other errors. Other maps compromise, like the Winkel Tripel, so named because it tries to strike a balance between three kinds of distortion.

Starting in 2006, Dr. Gott and David Goldberg, a cosmologist at Drexel University in Philadelphia, developed a scoring system that could sum up these different kinds of error. The Winkel Tripel beat out other major contenders. But one big source of distortion persisted: a mathematical incision, often running from pole to pole down the Pacific. The resulting shape can never again be stretched and pulled back into the unbroken surface of a sphere. “This does violence to the globe,” Dr. Gott said.

His new kind of double-sided map, crafted with Dr. Goldberg and Robert Vanderbei, a mathematician at Princeton, skips the topological violence entirely. The map simply continues over the edge. You could stretch a string over the side; an ant could walk there. Without any cut, the map’s Goldberg-Gott distortion score blows all other maps currently in use out of the water, the team reports in a draft study.

Cartographers who regularly study world maps — perhaps fewer than 10 people — will now have time to react. “It never came up to me that it could be done in this way,” said Krisztián Kerkovits, a Hungarian cartographer working to develop his own projections.

But while the new map excels at addressing distortion, Dr. Kerkovits said it also introduced a new weakness. You can see only half of the planet at once, unlike the Winkel Tripel and Mercator. That undermines the basic premise of flaying out the whole world for inspection on a single page or screen.

To Dr. Gott, this is no different than the 3-D globe itself. But Dr. Kerkovits isn’t quite sure: After all, you can always rotate a globe slightly to see the neighbors of any chosen point. But in the double-sided map, you might have to flip the entire thing.

Ultimately a map’s success depends on which applications it’s used for, and how its popularity grows over time. Dr. Gott, whose paper also presents double-sided projections of Jupiter and other worlds, envisions the new map style as a physical object to turn over in your hands.

You could cut one out of a magazine, or you could store a whole stack of them in a thin sleeve, showing different planets or different data layers. And he hopes you may be tempted to try to print out and make your own using the appendix of his paper.

“Glue it back to back with double-stick tape — I think that’s better than Elmer’s Glue, but you can use glue,” Dr. Gott said. Then cut it out. “Maybe use card stock paper,” he added.

Source: Read Full Article