Réunion, a French island in the western Indian Ocean, is a jigsaw of two massive shield volcanoes. The younger, Piton de la Fournaise or “peak of the furnace,” is a furious factory of lava, erupting every eight months on average over the last four decades.

That hellish environment makes it an ideal real-world laboratory for studying the internal viscera of volcanoes, about which scientists know surprisingly little. The more they map out, the better they grow to understand why, how and when volcanoes all over the world will next erupt.

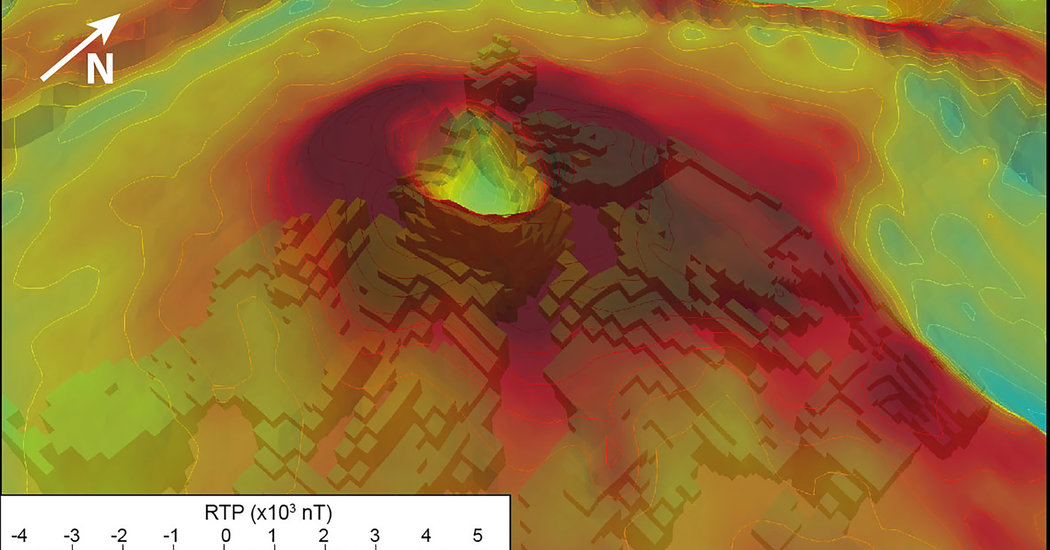

In a study published this month in Scientific Reports, volcanologists reported using a novel technique to map out 58 square miles of Piton de la Fournaise’s shadowy underworld. Their survey revealed a 3D view of its insides, from the plumbing network of superheated hydrothermal fluids to scores of faults that allow magma to sneak up to the surface during eruptions.

The success of this technique on Réunion means that it could be deployed elsewhere, said Marc Dumont, a geophysicist at the Sorbonne University in Paris and the lead author of the study, from lava effusing mountains like Hawaii’s Kilauea to the more explosive peaks in the volcanic spine running up America’s Pacific Northwest.

Piton de la Fournaise is a byzantine volcano, comprehensively monitored by scientists as it is regularly modified by eruptions. Spidery tendrils of magma escape through lines of weakness. When molten material meets the groundwater cycling through the volcano’s uppermost segments, powerful explosions can happen without warning, much like the lethal detonations that recently rocked New Zealand’s White Island. Old faults can suddenly slip and cause parts of the volcano to catastrophically collapse.

These features control how future eruptions manifest, so finding out where they are is of paramount importance.

One way to locate these subterranean features is to use instruments to see how well the rocks below conduct electricity. Scorching, circulating water is highly conductive. Old volcanic rock that has been degraded by it has water inside its Swiss cheese-like holes, making it relatively conductive. Newly cooled, structurally sound lava flows are much more electrically resistant.

Deploying electrical resistivity-detecting instruments on an active volcano can be both dangerous and time consuming. Often, expeditions must choose between a high-resolution underground map of a small area or a low-resolution map of a larger space.

Scientists had previously traipsed across the Piton de la Fournaise by foot, deploying equipment to reveal parts of its internal structure. To speed things up, they took to a helicopter.

Hewing disquietingly close to the volcano over four days in 2014, the helicopter’s winch held a sizable hoop that could electrically excite the rocks below. In response, electromagnetic threads snaked back up from the volcano, which were detected by the helicopter. These invisible strings differed, depending on the properties of the rocks, which allowed scientists to identify individual ingredients and layers of Réunion’s youthful volcanic cake down to a depth of 3,300 feet.

Scientists were previously aware of the existence of some of the volcano’s rift zones, faults and fluid networks. But they now have a 3D schematic providing an unparalleled peek into the volcano’s active subsurface, showing with precision where its magmatic appendages and pathways, rocky scars and hydrothermal pipes are in relation to each other.

“Our continuing ability to image the internal structure of volcanoes in 3D is revolutionizing how we understand volcanism,” said Sam Mitchell, a submarine volcanologist not involved with the work, and who recently joined an aquatic voyage to peer into the heart of a massive underwater volcano near Oregon. No matter which volcano is being mapped, he said, the goal of these projects is the same: to identify hazards and save lives.

Source: Read Full Article